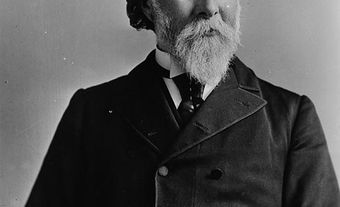

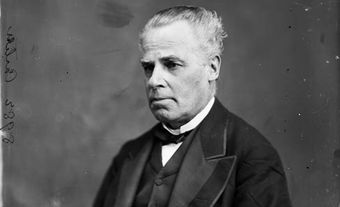

Early Life and Career

Hector-Louis Langevin’s father was a shopkeeper and office-holder who was part of a rising middle class in Québec City. Hector-Louis, one of 13 children, received a religious education. His brothers Jean and Edmond would go on to become the bishop of Rimouski and the vicar general of the dioceses of Québec and Rimouski, respectively. The three brothers were very close and wielded considerable behind-the-scenes power in the politics of the day. They are often seen to exemplify the union of Church and State in French Canada in the late 19th century.

Langevin studied law, articling under Augustin-Norbert Morin and George-Étienne Cartier. But he had already turned to journalism in 1847 before he was admitted to the Bar in October 1850. He became editor of Mélanges religieux and contributed to Journal d’agriculture. He later became editor of Le Courier du Canada in 1857, served as political editor of Le Canadien from 1872 to 1875 and became owner of Le Monde in 1884.

In his journalistic work, Langevin was mainly interested in politics. His writing reveals him to be a cautious nationalist. He was opposed to radicalism and the annexation to the United States called for by the Tories of the day and by supporters of Louis-Joseph Papineau. He advocated instead for a federation of British North American colonies. In many of his articles, he put forward arguments that would later be used by the Fathers of Confederation.

Political Career

Langevin was elected to the municipal council of Québec for the Palais Ward in 1856. He then served as mayor of Québec City in 1858, holding the office until 1861. During his tenure, Langevin’s main projects included an overhaul of the city’s finances and construction of the North Shore railway.

In the election of 1857–58, he was sent to the Legislative Assembly, representing Dorchester as a member of the Parti bleu. He served as solicitor general for Canada East from 1864 to 1866, and as postmaster general from 1866 to 1867. He also served as head of the St-Jean-Baptiste Society in Québec City (1861–63) and of the Institut canadien (1863–64).

Confederation

As a member of cabinet during the Great Coalition, Langevin defended Québec’s interests at the Charlottetown and Québec Conferences in 1864. He also attended the London Conference in 1866.

His speeches and arguments during the Confederation conferences and debates show him to be a passionate risk-taker who demonstrated that the French minority was capable of exerting remarkable influence. For him, the objectives of Confederation were to defend the interests of the country and to protect the rights of French Canadians. He maintained that Canada East represented a distinct society and that French Canadians were a separate people. He also took it upon himself to interpret the demands of the Catholic hierarchy. Refusing to accept any position that made Québec inferior, he was distrustful of the English and combative in protecting the interests of the French. He rejected any measures that could ostensibly dismantle French customs and laws. He believed that the federal system was the best way to preserve French Canadian traditions and culture, and to ensure political equity with the rest of Canada.

At the London Conference, Langevin influenced his colleagues to respect the 72 Resolutions established at the Québec Conference. This credits him with helping draft the final text of the British North America Act.

See also Québec and Confederation.

Political Career after Confederation

After 1867, Langevin represented Dorchester County both in Québec and federally until dual representation was abolished in 1874. In Ottawa, Langevin was secretary of state and superintendent of Indian Affairs in Sir John A. Macdonald’s cabinet (1867–69) and minister of Public Works (1869–73). He took a centralist position, which contributed to some of the difficult federal–provincial relations that grew in the years following Confederation (see Distribution of Powers).

He succeeded Sir George-Étienne Cartier as leader of the Québec wing of the Conservative Party (1873–91). But he was implicated in the Pacific Scandal of 1873 and did not stand in the next federal election. He tried to return to political life in 1876, but was delayed by a contested election in Charlevoix. In 1878, after a defeat in Rimouski County, he was elected in Trois-Rivières.

Langevin had considerable influence in the Macdonald government following the 1878 election. Throughout the 1880s, Langevin was Macdonald’s right-hand man in Québec (Macdonald referred to him as “a first-rate administrator”). He headed the Post Office (1878–79) and then Public Works (1878–91).

Residential Schools

During his tenure as minister of Public Works, Langevin was among the first architects of the residential schools system, which was designed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. Langevin presented a three-school pilot program to the House of Commons in May 1883. In his remarks, he suggested that the government should establish three “Indian industrial schools” in the North-West Territories, citing the success of such schools in the United States. In light of the US model, he went on to say that the children must be separated from their parents in order for the schools to be effective:

The fact is, that if you wish to educate those children you must separate them from their parents during the time they are being educated. If you leave them in the family they may know how to read and write, but they still remain savages, whereas by separating them in the way proposed, they acquire the habits and tastes — it is to be hoped only the good tastes — of civilized people.

He then described the location for the first three residential schools to be established by the Macdonald government — in Qu’Appelle, Battleford and High River — and outlined matters of budgeting, staffing, organization and more.

An estimated 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were taken from their families and forced to attend residential schools. For over 100 years, residential schools disrupted lives and communities, causing long-term trauma that continues to reverberate.

Late Life and Career

Conflicts in the Conservative Party undermined some of Langevin’s influence. He was compromised by another scandal when he was linked to MP Thomas McGreevy’s patronage. He was driven out of cabinet in 1891 amid accusations of corruption in his department. Though he was later exonerated, he remained in the backbenches until he retired from politics in 1896.

The events surrounding his retirement — and a promised promotion to lieutenant-governor of Québec that was never granted — were seen as a disgraceful end to his long political career. They left Langevin devastated, and he hid from the public arena until his death in June 1906.

Legacy

Sir Hector-Louis Langevin is remembered for attending all three conferences leading to Confederation and for his demonstration of a strong national sentiment. He embodied the centralizing spirit of the country’s founders (see Federalism) and gave support to a national economic agenda, the colonization of the West, the establishment of a transcontinental railway and industrialization through protectionism. His career was long and intense. He was a pillar of the Conservative Party and a cabinet minister for nearly 30 years.

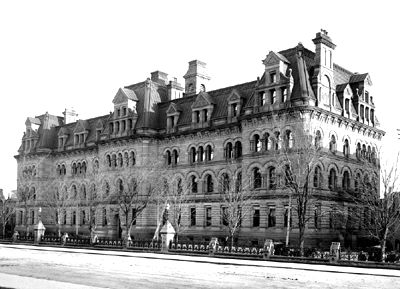

In June 2015, the names of the Langevin Bridge and Langevin School in Calgary and of Langevin Block, home of the Prime Minister’s Office in Ottawa, drew public scrutiny for their connection to a politician involved in the creation of the residential schools system. This occurred shortly after the official closing ceremonies of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Ottawa. The TRC’s final report includes a quote from Langevin’s 1883 remarks before the House of Commons. As Linda Many Guns, a Native American Studies professor at the University of Lethbridge, explained to the CBC, “The problem was [Langevin’s] role in advocating very strongly for the removal of the culture from [Indigenous] children when they went into these systems.” In early 2017, Calgary city council voted to change the name of the bridge to Reconciliation Bridge. On 21 June 2017, National Aboriginal Day, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Langevin Block would be renamed Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom