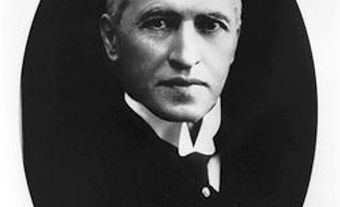

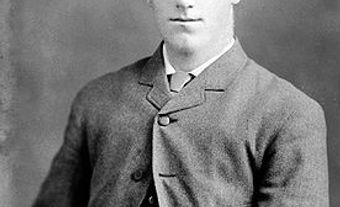

Sir Clifford Sifton, PC, KCMG, KC, lawyer, politician, businessman (born 10 March 1861 near Arva, Canada West; died 17 April 1929 in New York City, New York). Sir Clifford Sifton was one of the ablest politicians of his time. He is best known for his aggressive promotion of immigration to settle the Prairie West. Under his leadership, immigration to Canada increased significantly; from 16,835 per year in 1896 to 141,465 in 1905. A Liberal politician of considerable influence and vision, he was also a controversial figure. Sifton promoted a single education system and opposed the public funding of denominational schools, largely disregarding the concerns of French Catholics. He also showed little interest in the Indigenous peoples of the Prairies; he oversaw cuts to Indigenous education and approved Treaty 8. His brother, Arthur Lewis Sifton, was premier of Alberta from 1910 to 1917.

Early Life and Education

Clifford Sifton was born in 1861 to Kate Watkins and John Wright Sifton. A farmer at the time of Clifford’s birth, John Sifton was a Wesleyan Methodist. He supported the politics of George Brown and Alexander Mackenzie, and later became a railway contractor and businessman. In 1874, he received government contracts to build two sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), as well as a telegraph line north of Winnipeg. Thus, the family moved to Manitoba in 1875.

Clifford Sifton returned to Ontario in 1876, where he attended Victoria College in Cobourg. Partially deaf due to a childhood attack of scarlet fever, Sifton graduated at the top of his class in 1880. After two years articling with the Samuel Clarke Biggs law firm in Winnipeg, he was called to the Manitoba Bar in 1882. He then established a law practice with his brother, Arthur Lewis Sifton, in Brandon, Manitoba.

Manitoba Politics

Sifton’s family was active in national and local politics. His father had supported Alexander Mackenzie’s campaigns and twice won election to the Manitoba legislature (1878 and 1881). Clifford Sifton supported his father’s re-election campaigns in 1882 and 1886, both of which were unsuccessful. In 1888, Sifton himself ran for election to the Manitoba Legislature as a Liberal candidate. He was elected as an MLA for Brandon North. He served in the new government under Thomas Greenway.

The Manitoba Liberals opposed the policies of Prime Minister Sir John A Macdonald’s Conservative government; particularly the monopoly of the CPR. The Liberals wanted more competition and reduced freight rates. They also distrusted the provincial government under John Norquay, which they believed was controlled by the federal government. When the Manitoba Liberals won the provincial election in 1888, it marked a change in policy toward greater provincial rights. This quickly became apparent in the debate over the Manitoba Schools Question.

Manitoba Schools Question

In 1890, Greenway’s Liberal government established a “national school system” in Manitoba. Under the Public Schools Act of 1890, only “national schools” would be funded by the provincial government. Denominational schools would be allowed, but they would not receive any provincial funding. This, however, challenged the Manitoba Act of 1870; it had established a system of publicly funded separate schools for (French) Catholics and (English) Protestants. The Catholic minority promptly challenged the new legislation; they launched Barrett v. City of Winnipeg in 1890 and Brophy and others v. Attorney-General of Manitoba in 1893. The cases were heard by the Manitoba courts, the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (Canada’s highest court of appeals at the time).

Sifton was appointed attorney general and provincial lands commissioner in 1891. He was also made minister of education in 1892. He ably defended the national school system and played a key role in negotiating a settlement with the federal government. Known as the Laurier-Greenway compromise, the settlement allowed limited religious instruction in schools. It also permitted bilingual education in schools where 10 or more students spoke a language other than English. (See also Manitoba Schools Question.)

Railway Development

With the election of the Manitoba Liberals in 1888, the monopoly of the CPR came to an end. This allowed completion of the Red River Valley Railway and a reduction in freight rates. However, railway expansion stalled in Manitoba. This was largely due to the problems of financing construction. In 1895, Sifton created a new system of financing railway construction in which the provincial government guaranteed the principal and interest on railway bonds. He also worked with railway contractors Donald Mann and William Mackenzie to complete the Lake Manitoba Railway; it became part of the Canadian Northern Railway system in 1899. (See also Building the Canadian Northern Railway.)

Federal Politics

After negotiating the Laurier-Greenway compromise on the Manitoba Schools Question, Sifton joined Wilfrid Laurier’s government on 17 November 1896. He became federal minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs; as such, he was responsible for immigration and settlement of the prairies. (See History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies.)

Crow’s Nest Pass Agreement

Sifton became well known for his energy, mastery of political organization and incisive analytical capacity. His dynamic view of the role of government in stimulating development, and his broad grasp of Canada’s material and economic problems set him apart. He was the principal negotiator of the Crow’s Nest Pass Agreement with the CPR. The agreement gave the railway a cash subsidy ($3.3 million) and access to the British Columbia interior; in exchange, the rates for shipping grain and flour east (which benefited Prairie farmers) and manufactured goods west (which benefited settlers) were reduced.

Immigration

Sifton’s promotion of immigration was an immense success. Under his leadership, the department of the interior aggressively promoted settlement in Western Canada. It took advantage of a strong economic recovery that made farming in the West more attractive. The department targeted agricultural settlers in the United States, Britain and — most controversially — east-central Europe.

English-speaking Canadians were concerned that immigrants from eastern and central Europe would be a threat to their culture. Against attacks by these nativists, Sifton defended the “stalwart peasants in sheep-skin coats” who were turning some of the most difficult areas of the West into productive farms. (See also Ukrainian Settlement in the Canadian Prairies.) Between 1896 and 1905, the annual number of immigrants entering Canada rose from 16,835 to 141,465. However, anyone considered to be a non-agricultural immigrant (e.g., southern Europeans, Blacks, British urbanites, East Asians) was discouraged.

Treatment of Indigenous Peoples

While Sifton wanted to settle European farmers in the West, he had little interest in the Indigenous peoples of that area. (See Plains Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) He not only cut costs in the Department of Indian Affairs, but also to Indigenous education. His paramount interest was in opening up the land for settlement and speculation. In 1899, he approved Treaty 8. This allowed the Crown to secure almost 850,000 km2 in what was then the North-West Territories and British Columbia (now northern Alberta, northwest Saskatchewan, and parts of present-day Northwest Territories and BC). The primary motivation for the Crown was securing safe passage for gold prospectors headed for the Yukon. (See also Klondike Gold Rush.)

Yukon Gold Rush and Alaska Boundary Dispute

Sifton was also responsible for the administration of the Yukon during the Klondike gold rush. One of his most controversial policies was his attempt to support capitalist investment in the Yukon. This marked a shift from individual placer-mining operations to large-scale mechanized mining for gold. (See also Gold Rushes in Canada.) Sifton also failed to negotiate a direct route from the Yukon goldfields to the Pacific, through the Alaskan Panhandle. At issue was the disputed boundary between southeastern Alaska and the BC coast. Sifton was in charge of presenting Canada’s case in 1903 to the Alaska Boundary Tribunal. It decided in favour of the American claim. (see Alaska Boundary Dispute.)

Resignation and Later Life

Sifton resigned from Cabinet on 27 February 1905. This followed a dispute with Prime Minister Laurier over school policy for Alberta and Saskatchewan. (See Autonomy Bills.) Sifton believed that the new provinces should ideally have a single school system. He was concerned by education clauses that seemed to grant privileges to the Catholic minority. He remained a Member of Parliament until 1911, when he broke with the Liberal Party on reciprocity with the United States. He didn’t run for Parliament again; but he did support the anti-reciprocity Conservatives. (See Anti-Reciprocity Movement.) This contributed to their victory in the general election of September 1911.

Sifton was chairman of the Commission of Conservation from 1909 to 1918. He promoted a wide spectrum of conservation measures intended to efficiently manage natural resources. He was knighted on 1 January 1915, becoming Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George.

With four sons in the Canadian military, Sifton supported Canada’s involvement in the First World War. He and his wife, Elizabeth Armanella (“Arma”) Burrows, spent much of the war in Britain to be closer to their sons. When they returned to Canada in 1917, the country was in the middle of a conscription crisis. (See Military Service Act.) Sifton helped convince pro-conscription Liberals in the West to join with Robert Borden to form the Union Government in 1917; however, he was later disappointed by the Union government’s failure to adopt a domestic reform agenda, beyond its focus on the war. In 1925, he gave several speeches in support of the Liberals under William Lyon Mackenzie King. Like Sifton, Mackenzie King believed that Canada should be more independent from Britain.

Sifton died of heart failure in New York City, where he had gone to consult a specialist. He left an estate valued at nearly $10 million. However, he was highly secretive about his private and business affairs. Sifton had invested in real estate early in his career, and in resources and transportation following his resignation from cabinet in 1905. His most important acquisition, however, was the Manitoba Free Press (now the Winnipeg Free Press) in 1898. Its editor, J.W. Dafoe, became his closest confidant and eventual biographer.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom