Early Life and Education

Romanow was born in Saskatoon on 12 August 1939, to Michael and Tekla Romanow. Along with other Ukrainians, Michael had moved to Saskatchewan in the late 1920s, seeking an escape from poverty in eastern Europe. His wife Tekla and their daughter Ann remained in the village of Ordiv, in western Ukraine, until they joined Michael in Canada in 1938. Michael worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and bought a small house on the west side of Saskatoon, where Roy was raised (the only one of the four born in Canada). Roy grew up immersed in the life and culture of his parents’ immigrant community, and learned Ukrainian as his first language.

Roy attended Westmount Community School and Bedford Road Collegiate. As a student he began part-time broadcasting, doing paid work for local radio stations as both a disk jockey and an announcer for hockey and baseball games. After high school, he attended the University of Saskatchewan and became active in student politics, especially in the public debate then dominating Saskatchewan over the controversial introduction of publicly-funded medicare by the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) government.

Romanow earned an Arts degree from the university in 1960 and a Law degree in 1964. In 1967 Romanow married Eleanore Boykowich, a radio writer and advertising producer. They did not have children.

Provincial Politics

At university, Romanow had made important contacts within the CCF party, and after graduation — while articling to become a lawyer — he spent time as a CCF organizer. With his radio experience, he soon became the party’s provincial chair for publicity.

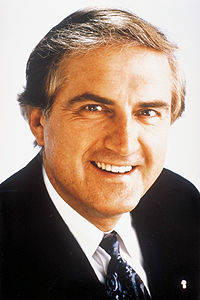

In 1966 he won the uncontested nomination as the CCF candidate in his provincial riding of Saskatoon-Riversdale. With his youthfulness, his media savvy and his telegenic looks, Romanow became a CCF star during the 1967 election campaign. Although his party lost the election, Romanow won his riding and took a seat on the opposition side of the legislature in Regina, where he established himself as a skilled debater and orator.

In 1970, Romanow contested the leadership of the Saskatchewan New Democratic Party (NDP) — formerly the CCF. Although he won the early voting rounds at the leadership convention, he was ultimately defeated by former cabinet minister Allan Blakeney, the more experienced candidate. The Blakeney New Democrats won the 1971 election and Romanow was named deputy premier, house leader and attorney general.

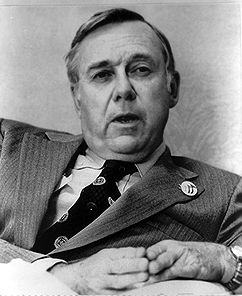

Patriation of the Constitution

The NDP were re-elected in 1975 and 1978, after which Romanow added the newly-created post of intergovernmental affairs minister to his list of responsibilities. In this role he became a major figure in the years of federal-provincial negotiations and political wrangling that led to the drafting of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the patriation of the Constitution in 1982. Romanow's close relationships with Jean Chrétien (then federal justice minister) and Ontario attorney general Roy McMurtry were instrumental in working out the final constitutional package.

In the provincial election that same year, the NDP — widely viewed as consumed by constitutional matters, and out of touch with the local concerns of Saskatchewan voters — were defeated by the Progressive Conservatives (PC). Romanow himself was the highest-profile casualty of the election, narrowly defeated in own riding by a 23-year-old university student.

Out of office for the first time in 16 years, Romanow briefly practised law, and co-authored a book published in 1984, Canada Notwithstanding, about the negotiations that had brought about the new Constitution.

In the 1986 provincial election Romanow re-captured his old constituency for the NDP. He then succeeded Blakeney as leader in 1987, becoming leader of the opposition in the Saskatchewan legislature, where he led the battles against the privatization of Crown corporations being carried out by the Tory government of Premier Grant Devine.

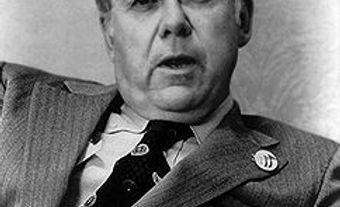

Premier

On 21 October 1991 — despite having been branded by Conservatives as “a man of the ‘70s” — Romanow led the New Democrats to a sweeping election victory, winning 55 of 66 seats in the legislature. “It will take a lot of hard work, a lot of tough decisions, and a little bit of luck, but I'm confident that we, the people of Saskatchewan, can do it,” Romanow said on election night.

Romanow became premier of a province on the verge of bankruptcy. Faced with dwindling government revenue and rising public debt — including the worst debt and deficits in Canada — Romanow’s government cut departmental budgets and public-service jobs, and capped public-sector wage increases. He also reduced Cabinet minister salaries, as an important symbolic measure for the belt-tightening occurring elsewhere.

As the national constitutional debate roared back to life under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Romanow was again prominent in the negotiations that led to the controversial Charlottetown Accord. Although the Accord ultimately failed, Romanow was able to escape the Saskatchewan public’s resentment of the process, largely thanks to his reputation, and his ongoing success at dealing with the province’s severe fiscal crisis.

In the 1995 provincial election, following the first balanced budget in Saskatchewan in 12 years, Romanow’s NDP won a renewed majority, taking 42 of 58 seats. Despite having put Saskatchewan’s fiscal house in order, Romanow could do nothing to control plummeting global crop prices. In its second term, his government was dogged by resentment from struggling farming families, who blamed the NDP for ignoring the needs of rural areas.

In the 1999 election, Romanow lost the support of farmers struggling through their worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. The NDP won only a minority government, taking almost every urban seat, but losing virtually every rural seat to the new, right-wing Saskatchewan Party. Romanow formed a governing coalition with the Liberals.

On 26 September 2000, after a lifetime of public service and nine years as premier, Romanow announced he would resign. He was succeeded the following year as party leader by Lorne Calvert.

Health Care

Romanow rejected requests from both the NDP and the Liberals to run for federal office. Instead, in 2001, he was appointed by Prime Minister Jean Chrétien to lead a commission tasked with finding ways to ensure the sustainability of the public health system. The Royal Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada held hearings across the country and published its much-awaited report in 2002. Dubbed the “Romanow Report,” it included recommendations on reforming medicare, one of which was that the federal government provide an additional $15 billion for health care to provinces and territories over the next three years. Critics said that Romanow was simply calling for more public money, rather than coming up with innovative ways to ease the health care burden on governments.

In the wake of the commission report, Romanow remained a vocal advocate for universal health care. In a 2012 column, he urged Canadians not to give up on medicare. He argued that “a universal, single-payer, public insurance model is both less costly and produces better population health outcomes than multi-payer systems like the one that exists in the United States.” He said a move toward a private, for-profit model would be a backward step. He also called for catastrophic drug costs, and aspects of home care and long-term care to be brought under the medicare system.

Post-Politics

In recognition of his life-long contributions to Canadian politics, Romanow was appointed to the Privy Council of Canada in 2003, and was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2004.

He serves on the Elections Canada Advisory Board, and is a member of the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation, an independent charity that promotes research in the humanities.

In 2016, Romanow was named co-chair of the board of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness. That same year he was named chancellor of the University of Saskatchewan for a three-year term.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom