Refugees are migrants who fled their countries of origin to escape persecution or danger and have found asylum in another country. Over time, Canada has been the landing ground for many migrants seeking refuge from all over the world. However, discriminatory immigration policies have also prevented some asylum seekers in need of protection from entering Canada (see Canadian Refugee Policy).

Key Concepts about Migration and Refugees

Migrant — Migrants are broadly defined as foreign-born or foreign nationals currently in a country other than their country of origin. Migrants can also be simply defined as people who move from one place to another, including across international borders.

Asylum seeker — Asylum seekers are migrants in search of protection outside of their countries of origin. However, unlike refugees, asylum seekers’ requests for protection have yet to be approved.

Refugee — The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) defines refugees as those who have fled from conflict and persecution to seek protection in another country. As such, refugees are generally asylum seekers who have been granted the right to asylum in another country (refugee status).

The 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees defines refugees as: “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

16th-19th Century: Early Refugee Cohorts to Canada

Canada is a nation of settler migrants. These migrants include the country’s original colonizers. These colonizers began arriving from Europe in the 15th century. Gradually, they took over Indigenous lands. After the establishment of the colonies, the first major cohort of immigrants to arrive in Canada came during and after the American Revolution (1775–83).

The United Empire Loyalists and Black Loyalists are regarded as among Canada's first refugee contingents. The Loyalists and Black Loyalists had sided or fought with the British during the American Revolution. After Britain’s defeat, many fled to Canada to avoid persecution for their political leanings. The Loyalists also included Quakers, Mennonites, and other nonconformists who feared persecution by the new American government.

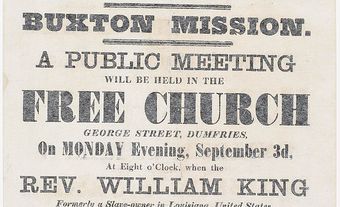

Before 1860, thousands of fugitive Black enslaved people also fled the United States to come to Canada. For those fleeing enslavement, Canada was seen as the final stop on the Underground Railroad. During this period, an estimated 30,000 African Americans came to Canada seeking protection.

Over the next generation, two groups of refugees, Mennonites and Doukhobors, arrived from Russia in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Both groups were persecuted under the Russian tsars. The Canadian government was desperately searching for farmers to settle the West and mainly resettled these groups to the Prairie Provinces.

19th-20th Century: Canada's Policies of Migrant Exclusion

Not all migrants were similarly welcomed into Canadian society. Canadian migration policy in the 19th–20th century was often restrictive on the basis of race and ethnic origin (see Canadian Refugee Policy). These racially discriminatory policies were used to deny refuge for many migrants. Chinese migrants to Canada were particularly the target of racist immigration policies. Many migrants had left China in the wake of socio-economic and political turmoil due to the disruption caused by Western imperial powers. However, Chinese migrants were seen as a threat by Canadian politicians who put in place racist restrictions on Chinese migration. In 1885, the Head Tax was put in place as a costly tax which only targeted Chinese migrants entering Canada. In 1924, the Chinese Immigration Act was passed and made Chinese immigration practically illegal except in a few cases.

In the 1930s, when German Jews seeking refuge from Nazi persecution sought sanctuary in Canada, the Canadian government was less than receptive. In 1939, hundreds of Jewish refugees onboard the ship MS St. Louis were turned away and had to return to Europe. Many of the passengers would end up later being persecuted and killed in Nazi-occupied Europe. Anti-Semitism permeated Canada, and there was little public support for, and much opposition to, the admission of refugees. While Canada eventually accepted some 4,000 Jewish refugees from Europe, this number was small compared to other countries. The US welcomed 240,000, Britain 85,000, China 25,000, and Mexico and Colombia some 40,000 between them.

This attitude of exclusion did not change until after the Second World War when Europe experienced its largest series of refugee migration. Canada then became much more receptive to refugees, largely due to its booming economy and the necessity to increase its workforce. Hundreds of thousands of displaced persons came to Canada, their journeys often subsidized by the Canadian government. Canada also began to play an increasingly active role in the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) organization in resettling refugees.

Late 20th Century: Refugees from the Cold War

Canada defined its reputation of welcoming refugees during the Cold War. By the end of the 1960s, the Canadian government gradually moved away from racially discriminatory migration policies. In 1969, Canada also signed on to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol which regulate international law regarding refugee rights.

In 1956, within months of the Hungarian uprising against the Soviet occupation, the Canadian government succumbed to domestic pressure, especially from ethnic and religious groups, and announced that it would accept a large number of Hungarian refugees. More than 37,500 arrived to Canada. Their acceptance while Cold War tensions were rising provided the West with an opportunity to criticize the Soviet Union and its allies’ invasion of Hungary. In 1968, with the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring, some 11,000 Czechs resettled to Canada. In 1972, Canada also accepted 7,000 Ugandan South Asians who were fleeing the repressive authoritarian regime of Idi Amin.

A more controversial group of refugees were the American war resisters. Also known as "draft evaders", these people fled across the border to escape mandatory service in the Vietnam War. Though some returned home after the war, many took up new lives in Canada. Equally controversial were the Chilean and other Latin American refugees forced out of Chile. These refugees had been forced to flee due to Augusto Pinochet's overthrow of Salvador Allende's Marxist government in 1973. However, the Canadian government did not want to alienate the American or new Chilean administrations. As such, Canada restricted the numbers of permitted entries, only resettling around 7,000 Chileans during the 30-year conflict.

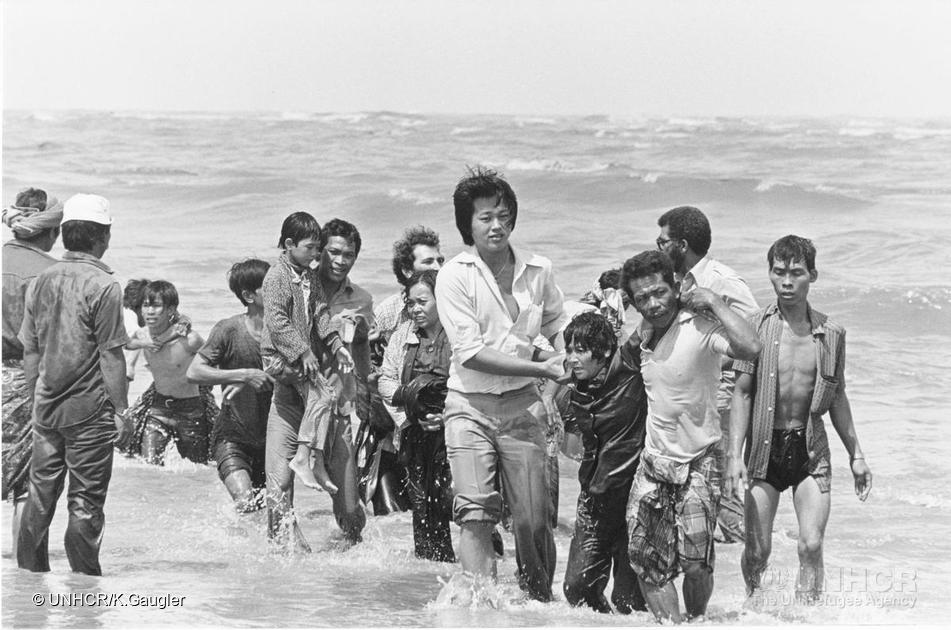

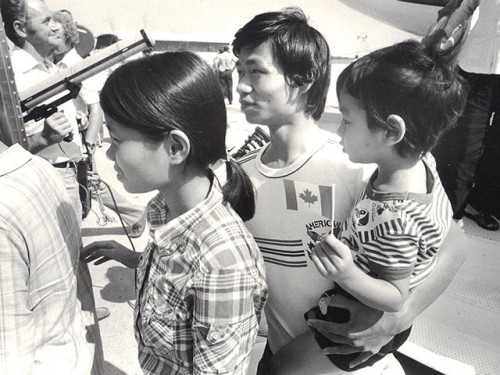

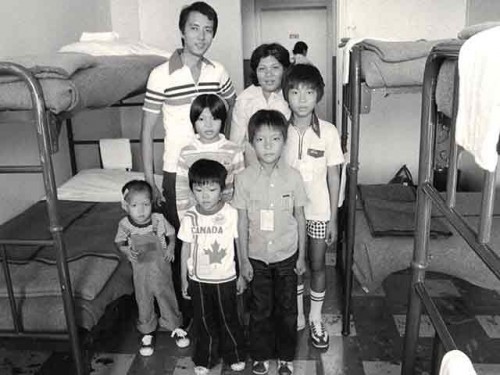

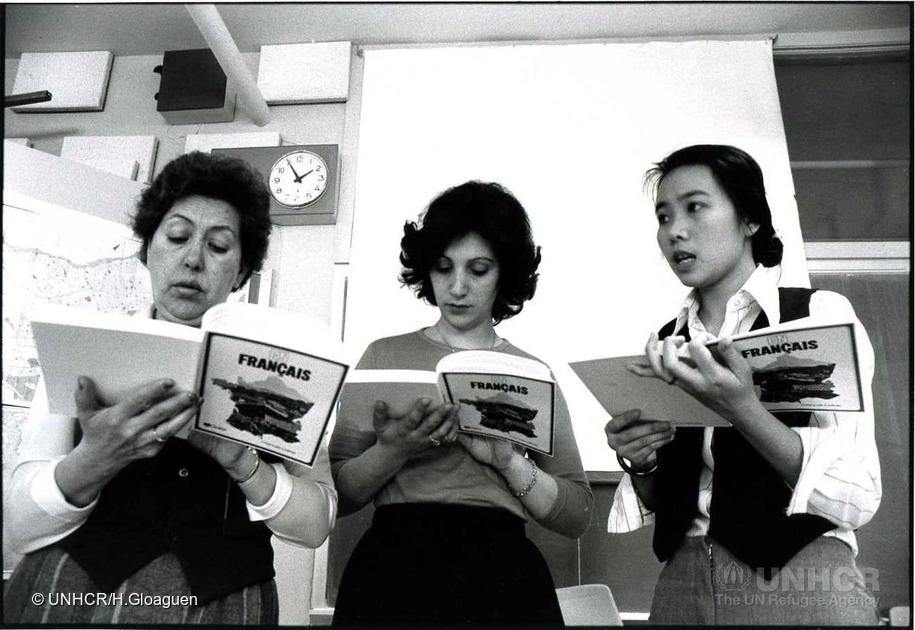

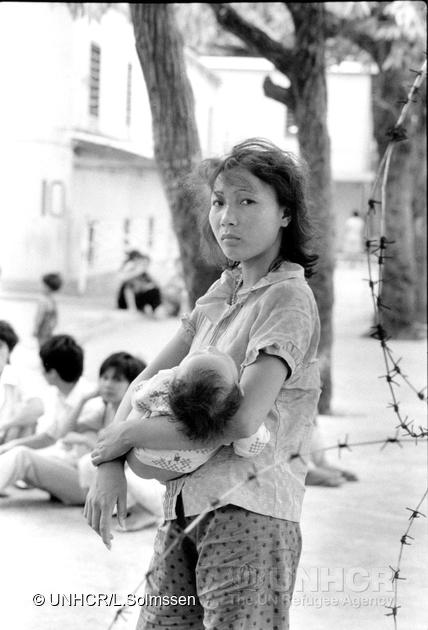

This is in sharp contrast to Canada's humanitarian action in welcoming refugees from Southeast Asia including Cambodians, Vietnamese, and Laotian "boat people" in the 1970s–1980s. Touched by the plight of the hundreds of thousands escaping from communism by taking to the high seas in unsafe boats, many Canadians offered to sponsor their journey to Canada. From 1978 onwards and into the 1980s, some 200,000 Southeast Asians refugees were resettled in Canada.

In 1986, in recognition of its exceptional contribution to refugee protection, Canada was awarded the Nansen Medal by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

21st Century: Modern Day Refugees and Asylum Seekers

From the 1990s–early 2010s, Canada enacted a number of policies aimed at curtailing the number of refugees. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the increased focus on national security, more resources were diverted to strengthen border enforcement. There was also a general attempt at decreasing numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. As a result, refugees were often wrongfully depicted as being linked to criminality, and terrorism.

The Conservative government under Stephen Harper was particularly characterized by this attitude. In 2009–2010, hundreds of Sri Lankan Tamil asylum seekers arrived in Canada on the MV Ocean Lady and MV Sun Sea. The government reacted by detaining the refugee claimants; with some families being imprisoned for years without much support. The Tamil refugees were depicted as being linked to terrorism and human smuggling, and not as “legitimate” refugees. However, many of the claimants have since then been found to be refugees through Canada's refugee determination system on the grounds that they were at risk of human rights abuses by the Sri Lankan government.

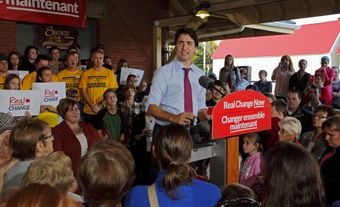

In the wake of the destructive and ongoing Syrian Civil War, more than 4 million people have been displaced by the conflict and more than 7 million continue to be internally displaced inside Syria. In November 2015, a newly elected Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau unveiled its resettlement response to the Syrian refugee crisis. The government committed to resettling 25,000 Syrian refugees by late 2015. Ordinary Canadians increased their support, including privately sponsoring refugees, aiding in resettlement activities, and setting up refugee health and legal clinics. By 2017, Canada had welcomed around 54,000 Syrian refugees to Canada. While Canada welcomed more Syrian refugees than the United States, this number was overshadowed by the efforts of many Middle Eastern and European countries. For instance, in 2017, there was an estimated 3.4 million Syrian refugees in Turkey and an additional 1 million in Lebanon. In Europe, Germany provided asylum to more than half a million asylum seekers while Sweden, a country with a population less than a third of the size of Canada, received 110,000 migrants. (See Canadian Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis.)

Since 2017 and the election of President Donald Trump’s administration in the US, thousands of asylum seekers have presented themselves at the US-Canadian border to claim refugee status. These asylum seekers seek refuge in Canada in reaction to the administration’s hostile rhetoric and policies on migration which could put them in harm’s way. Many of these migrants performed irregular crossings of the Canada-US border to circumvent the Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA). Irregular migrants crossed at unofficial entry points such as at Roxham road where they are stopped by the police. However, once in Canada, these migrants could apply for refugee status and have their cases heard. In March 2023, the STCA was renegotiated, restricting irregular migrants’ ability to claim asylum.

DID YOU KNOW?

The STCA considers the US to be a “safe third country” for asylum seekers to apply for refugee status. As such, many asylum seekers coming in from the US cannot apply for refugee protection at an official border crossing. However, critics argue that the US has harsher refugee policies which put asylum seekers at risk.

In 2018, Canada resettled more refugees than any other country. According to the annual global trends report released by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Canada took in 28,100 of the 92,400 refugees who were resettled across 25 countries. The report also shows that over 18,000 refugees became Canadian citizens that year, making it the country with the second highest rate of refugees to gain citizenship.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom