The Red River Resistance (also known as the Red River Rebellion) was an uprising in 1869–70 in the Red River Colony. The resistance was sparked by the transfer of the vast territory of Rupert’s Land to the new Dominion of Canada. The colony of farmers and hunters, many of them Métis, occupied a corner of Rupert’s Land and feared for their culture and land rights under Canadian control. The Métis mounted a resistance and declared a provisional government to negotiate terms for entering Confederation. The uprising led to the creation of the province of Manitoba, and the emergence of Métis leader Louis Riel — a hero to his people and many in Quebec, but an outlaw in the eyes of the Canadian government.

Red River Colony

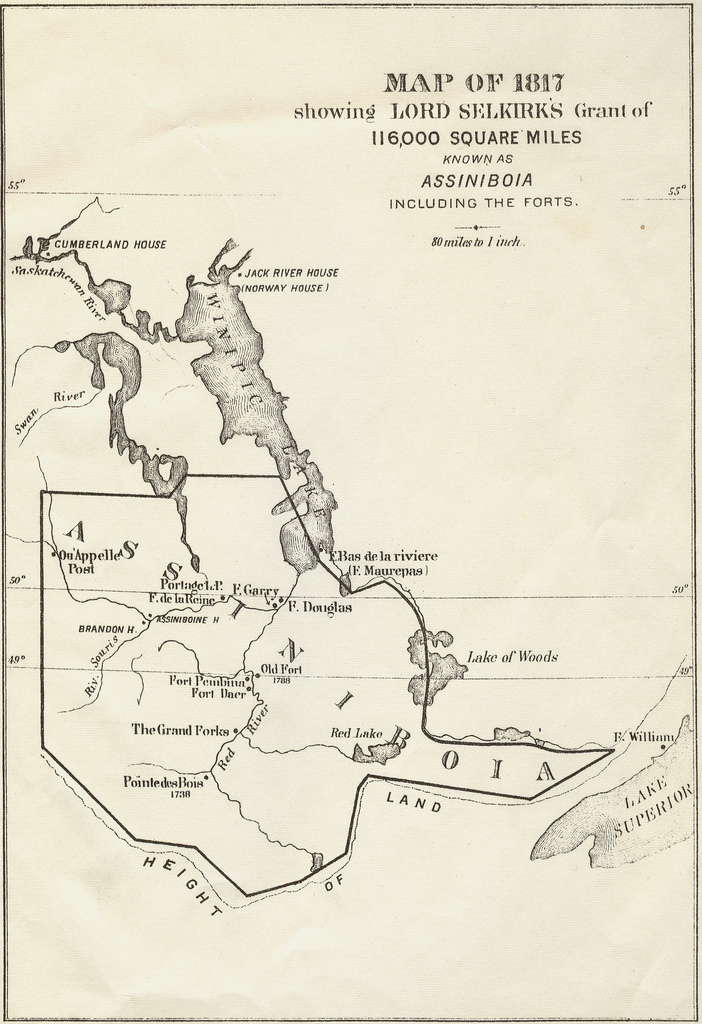

The Red River Colony was founded in 1812 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk. It was initially populated by Scottish settlers. It was located at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers (what is now downtown Winnipeg). The area had been a rendezvous location for the fur trade for many years. The North West Company arrived there to build Fort Gibraltar in 1809. The Hudson’s Bay Company had earlier established a small depot across the river, at what is now St. Boniface. The Assiniboine (Nakoda) people had previously controlled access to the area. By 1812, it was also home to Ojibwe, Cree traders and Métis buffalo hunters. Most Métis were the descendants of French and English voyageurs and coureurs de bois. They had come west with the fur trade and settled among Indigenous communities.

After 1836, the colony was administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). It was then populated mainly by francophone and anglophone Métis people.

Hudson’s Bay Company Leaves Red River

The Red River inhabitants were continually in conflict with the HBC. One of the main issues was trading privileges. (See also: Pemmican Proclamation; Battle of Seven Oaks.) By the 1850s, the HBC’s rule over Rupert’s Land was under attack from Britain, Canada and the United States. By the 1860s, it had agreed to surrender its monopoly over Rupert’s Land and the North West, including the Red River settlement.

During the lengthy negotiations to transfer sovereignty of the territory to Canada, Protestant settlers from the East moved into the colony. Their obtrusive, aggressive ways led the Roman Catholic Métis to want to preserve their religion, land rights and culture. Neither the British nor the Canadian government had any appreciation for the Métis people. No efforts were made to ease their fears. The transfer of Rupert’s Land was negotiated as if no one was there.

Louis Riel Steps Forward

In August 1869, Métis concerns were made worse. The Canadian government attempted to re-survey the settlement’s river-lot farms. These were typically long, narrow lots fronting the local rivers. They had been laid out according to the seigneurial system of New France. The government preferred square lots, which limited access to river water. (See also: Dominion Lands Act.) Many Métis did not have clear title to their land. Ottawa intended to respect Métis occupancy rights, but it gave no assurances that this would be the case. The Métis therefore feared the loss of their farms. Furthermore, William McDougall, a well-known Canadian expansionist, was appointed as the territory’s first lieutenant-governor. This fuelled tensions and fears among the Métis of English Canadian domination.

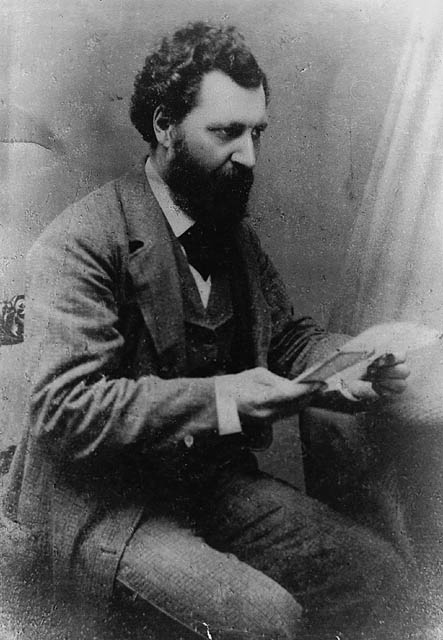

In early November 1869, Louis Riel emerged as Métis spokesman. He led a group from Red River that prevented McDougall and a land-survey party from entering the colony. Riel gathered support from both the francophone and anglophone Métis communities. He was aware that his people had to work with the more reticent, less organized anglophones to satisfy their grievances.

Local HBC officials remained neutral. But Métis opposition prevented the Canadian government from assuming control of the territory on 1 December 1869, as planned. This encouraged the resistors who had seized Upper Fort Garry, the main HBC trading post at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. They planned to hold it until the Canadian government agreed to negotiate.

Representatives of the resistance were summoned to an elected convention in December. It proclaimed a provisional government, which was soon headed by Riel. In January 1870, Riel gained the support of most of the anglophone community in a second convention. It was agreed that a provisional, representative government would be formed. It would discuss terms of entry into Confederation with the Canadian government.

Execution of Thomas Scott

Armed conflict persisted over the winter. Riel seemed in control until he made the colossal blunder of allowing the court-martialling and execution of a prisoner. Thomas Scott was one of a group of English-speaking Ontario settlers who opposed the provisional government. Amid the turmoil, Scott and some fellow Ontarians had been captured and imprisoned at Upper Fort Garry.

Scott was executed by firing squad, despite outside pleas that Riel not carry it out. Scott’s death inflamed passions among Protestants in Ontario. Canadian authorities were still willing to negotiate with Riel. But they refused to grant an unconditional amnesty to him and the leaders of the resistance.

Birth of Manitoba

The provisional government organized the territory of Assiniboia in March 1870. It enacted a law code in April. The Canadian government recognized the “rights” of the Red River settlers in negotiations in Ottawa that spring. But Red River’s victory was limited. On 12 May, a new province called Manitoba was created by the Manitoba Act. Its territory was severely limited in contrast to the vast North West, which would soon be acquired by the Canadian government. Even within Manitoba, public lands were controlled by the federal government. Métis land titles were guaranteed, and 607,000 hectares were reserved for the children of Métis families. However, these arrangements were mismanaged by later federal governments.

The Métis nation did not flourish in Manitoba after 1870. Ottawa granted no amnesty for Louis Riel and his lieutenants. They fled into exile just before the arrival of British and Canadian troops in August 1870.

The Red River resistance had won its major objectives. The colony became a distinct province with land and cultural rights guaranteed. But the Métis soon found themselves so disadvantaged in Manitoba that they moved farther west. They made another, more violent and tragic attempt to assert their nationality under Riel in the North-West Resistance of 1885.

Resistance or Rebellion?

The Red River Resistance and North-West Resistance are known by many names. These include the “Riel Rebellions,” the “Manitoba Rebellion” and the “Saskatchewan Rebellion.” They are also known as the “Red River Rebellion,” the “1885 Resistance” and the “Northwest Rebellion.” The terms rebellion and resistance are synonyms. But whichever one is used changes the perspective on the events.

According to the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, for example, rebellion is defined as an “organized and armed resistance to an established government.” Resistance, meanwhile, means “resisting authority, especially in an occupied country.”

Indigenous studies scholars and many historians refer to the Métis and First Nations uprisings as resistances. This frames them as reactions against European colonization. This is because Métis and First Nations established self-governance on their own land long before Rupert’s Land was transferred to the Dominion of Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom