The development of steam-powered railways in the 19th century revolutionized transportation in Canada and was integral to the very act of nation building. Railways played an integral role in the process of industrialization, opening up new markets and tying regions together, while at the same time creating a demand for resources and technology. The construction of transcontinental railways such as the Canadian Pacific Railway opened up settlement in the West, and played an important role in the expansion of Confederation. However, railways had a divisive effect as well, as the public alternately praised and criticized the involvement of governments in railway construction and the extent of government subsidies to railway companies.

This is the full-length entry about Railway History in Canada. For a plain-language summary, please see Railway History in Canada (Plain-Language Summary).

Early Railways

In the early 17th century, mining railways were introduced to England; powered by horses, these early railways carried ore and coal from pitheads to water. In Canada, a primitive railway of this type may have been used as early as the 1720s to haul quarried stone at the fortress of Louisbourg. In the 1820s, an incline railway of cable cars, powered by a winch driven by a steam engine, was used to hoist stone during the building of the Quebec Citadel. Another railway was used during the building of the Rideau Canal to carry stone from the quarry at Hog’s Back in Ottawa.

The Railway Age

Steam locomotion, together with the low rolling friction of iron-flanged wheels on iron rails, enabled George Stephenson (the first of the great railway engineers) to design and superintend the building of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830). This began the railway age in England. By 1841, there were some 2,100 km of rail in the British Isles, and by 1844 the frenetic promotion of railways aptly called “The Mania” was underway. Many of the lasting characteristics of the railway were established in this early stage: steam locomotion, the standard gauge (1.435 m), and the rolled-edge rail (which bellied out on the underside for strength).

Early Railways in British North America

Railway fever came a little later to British North America; the colony had a small population and much of its capital was tied up in the expansion of its canals and inland waterways. Nevertheless, it did not take long for politicians and entrepreneurs to realize the potential benefits. The Province of Canada (1841–1867) was an enormous country. Its roads were poor and its waterways were frozen for up to five months per year.

The first true railway built in Canada was the Champlain and Saint Lawrence Railroad from La Prairie on the St. Lawrence River to St. Johns on the Richelieu River (now Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu). Backed by John Molson and other Montreal merchants, the line opened officially on 21 July 1836. Built as a “ portage” between Montreal and Lake Champlain, in practice the railway carried little freight. (See also Canada’s First Railway.)

On 19 September 1839, the first railway in the Maritimes opened; the Albion Mines Railway was built to carry coal from Albion Mines some 9.5 km to the loading pier at Dunbar Point (near Pictou, Nova Scotia). The Montreal and Lachine Railroad (1847) was another short (12 km) line built to supplement water transportation.

Railway Mania

More ambitious was the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad, promoted initially by John A. Poor of Portland, Maine, and Canadian entrepreneur Alexander Tilloch Galt. The dual purpose of the line was to provide Montreal with a year-round ocean outlet and Portland with access to a hinterland. Promotion of the railway set a pattern often repeated later. In the initial enthusiasm, Montrealers subscribed £100,000 but paid only 10 per cent of that amount. Galt raised another £53,000 in England and mortgaged his land company to get the project moving.

But it was the Guarantee Act, 1849, sponsored in the Canadian legislature by Galt’s friend Francis Hincks, which ensured the railway’s completion (1853). Under the Act, railways that were longer than 75 miles (120 km) were eligible to receive a government grant that guaranteed interest of up to 6 per cent on half its bonds once half of the railway had been completed. While the Act established government assistance for railway construction, it also inspired a railway building mania in Canada, and led companies and governments to overextend themselves financially.

Another collaboration between Canadian and American interests lay behind the Great Western Railway, which began construction in October 1849 and was completed from Niagara Falls to Windsor, Canada West (Ontario), in January 1854. In this case Conservative politician and businessman Allan MacNab arranged for partners in Canada and the United States, and persuaded the legislature to proffer a loan of £200,000, profiting mightily himself.

The most ambitious pre-Confederation railway project in Canada was the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) — a bold attempt by Montreal to capture the hinterland of Canada West and traffic from American states in the Great Lakes region. The GTR aroused great anticipation, but Canadians had neither the money nor the technicians to build it. The success of Hincks and other promoters in raising money for the GTR and other railway projects was largely due to their determination and the seemingly unbounded enthusiasm of British investors for railways.

By the time it was completed from Sarnia to Montréal in 1860, the GTR was £800,000 in debt to the British banks of Baring Bros and Glyn Mills. Edward Watkin, sent out by head office to reorganize the railway, declared the GTR “an organized mess — I might say a sink of iniquity.” The GTR relied on government assistance in order to continue operations, and in 1862 the Grand Trunk Arrangements Act provided yet more resources to the railway company. The public, which had earlier been enthusiastic about the GTR’s potential, viewed such handouts with contempt and hostility.

Economic and Industrial Impact

The financial difficulties experienced by all early railways forced massive public expenditures in the form of cash grants, guaranteed interest, land grants, rebates, and rights-of-way. In return, the railways contributed to general economic developments, and the indirect benefits for business and employment were significant. Unlike canals, railways extended into new territories and pushed the agricultural and timber frontiers westward and northward.

The effect of railways on emerging urban centres was crucial and dramatic. Toronto’s dominant position in south-central Ontario was clearly established by its rail connections. It benefited from its connections with the Great Western and its central place on the GTR, neither of which it had done much to help build. It also tapped the northern hinterland via the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railway (completed to Collingwood, on Georgian Bay, in 1855, with a branch line to Belle Ewart on the south shore of Lake Simcoe), the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway (completed to Owen Sound, on Georgian Bay, in 1873), and the Toronto and Nipissing Railway (extended to Lake Simcoe in 1877). Toronto was also home to the first locomotive built in Canada; the Toronto No. 2 of the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron line was built by James Good of Toronto in 1853.

While railways were also constructed in sparsely populated and nonindustrial areas such as Newfoundland, they were not as profitable and tended to diminish in size and importance over time. The development of a Newfoundland Railway system is a case in point. In 1919, the Grand Trunk Railway was earning $16,000 per mile while the Newfoundland system was earning $1,500.

The railways played an integral role in the process of industrialization, tying together and opening up new markets while, at the same time creating a demand for fuel, iron and steel, locomotives, and rolling stock. The pioneer wood-burning locomotives required great amounts of fuel, and “wooding-up” stations were required at regular intervals along the line.

Entrepreneurs invested in the manufacture of almost everything that went into the operation of the railway, and consequently railways had a positive effect on levels of employment. Some small towns became railway service and maintenance centres, with the bulk of the population dependent on the railway shops; for example, the Cobourg Car Works employed 300 workers in 1881. The railway also had a decisive impact on the physical characteristics of Canadian cities: hotels and industries were built around tracks, yards, and stations, making the railway a central feature of the urban landscape.

The railway greatly stimulated engineering, particularly with the demand for bridges and tunnels. Canadians contributed a few inventions, notably the first successful braking system (W.A. Robinson, 1868) and the rotary snowplough (J.W. Elliott, 1869; developed further by O. Jull), which made possible safe, regular travel in Canadian winters. The great Canadian railway engineer Sir Sandford Fleming devised his famous zone system of time to overcome the confusion of clocks varying from community to community along the rail routes (see Invention of Standard Time).

The Transcontinentals

The second phase of railway building in Canada came with Confederation in 1867. As historian George Stanley wrote in The Canadians, “Bonds of steel as well as of sentiment were needed to hold the new Confederation together. Without railways there would be and could be no Canada.” In fact, the building of the Intercolonial Railway was a condition written into the Constitution Act, 1867. Because of the grand scale of the new nation, and the fact that political considerations often overrode economic realities (e.g., in the circuitous routes the Intercolonial and other railways took to avoid American territory), government assistance was crucial in building the transcontinental railways.

The Intercolonial was owned and operated by the federal government and was largely financed with British loans backed by imperial guarantees. Despite the badgering of commissioners determined to make political advantage, Fleming built the Intercolonial to the highest standards and completed it by 1876.

The Canadian Pacific Railway

In 1871, British Columbia was lured into Confederation with the promise of a transcontinental railway within 10 years. The proposed line — 1,600 km longer than the first US transcontinental — represented an enormous expenditure for a nation of only three and a half million people. Two syndicates vied for the contract, and it was secretly promised to Sir Hugh Allan in return for financial support for the Conservatives during the closely contested 1872 election. The subsequent revelation that Allan was largely backed by American promoters, and that he had sunk $350,000 into the Conservative campaign, brought down the government (see Pacific Scandal).

Did you know?

Treaties 1 to 7, concluded between the Crown and First Nations from 1871 to 1877, solidified Canada’s claim to lands north of the US-Canada border. They enabled the construction of a national railway and opened the lands of the North-West Territories to agricultural settlement. In exchange for their traditional territory, government negotiators made various promises to First Nations — both orally and in the written texts of the treaties — including special rights to treaty lands and the distribution of cash payments, hunting and fishing tools, farming supplies, and the like. These terms of agreement are controversial and contested. To this day, the Numbered Treaties have ongoing legal and socioeconomic impacts on Indigenous communities.

On 21 October 1880, the government finally signed a contract with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) Company, headed by George Stephen, and construction began in 1881. The “Last Spike” was driven on 7 November 1885 and the first passenger train left Montreal in June 1886, arriving in Port Moody, BC, on 4 July. Completion of the railway was one of the great engineering feats of the day and owed much to the indefatigable supervision of William Van Horne and the determination of Sir John A. Macdonald. While Macdonald’s government was criticized for the generous terms offered to the company, it considered the railway crucial to the nation.

Though ostensibly a private enterprise, the CPR was generously endowed by the federal government with cash ($25 million), land grants (25 million acres), tax concessions, rights-of-way, and a 20-year prohibition on the construction of competing lines on the prairies that might provide feeder lines to US railways. Whether or not the country received adequate compensation for this largesse has been hotly debated ever since. However, the CPR was built in advance of a market and by a very expensive route through the Canadian Shield of Northern Ontario. Macdonald’s controversial decision in favour of an expensive all-Canadian route seemed to be vindicated during the North-West Rebellion; how would the American government have reacted to Canadian troops moving across American territory? The CPR also had a profound effect on the settlement of the Prairie West, and new cities, from Winnipeg to Vancouver, were heavily dependent on the railway. Other western towns were strung out along the railway like beads on a string.

Did you know?

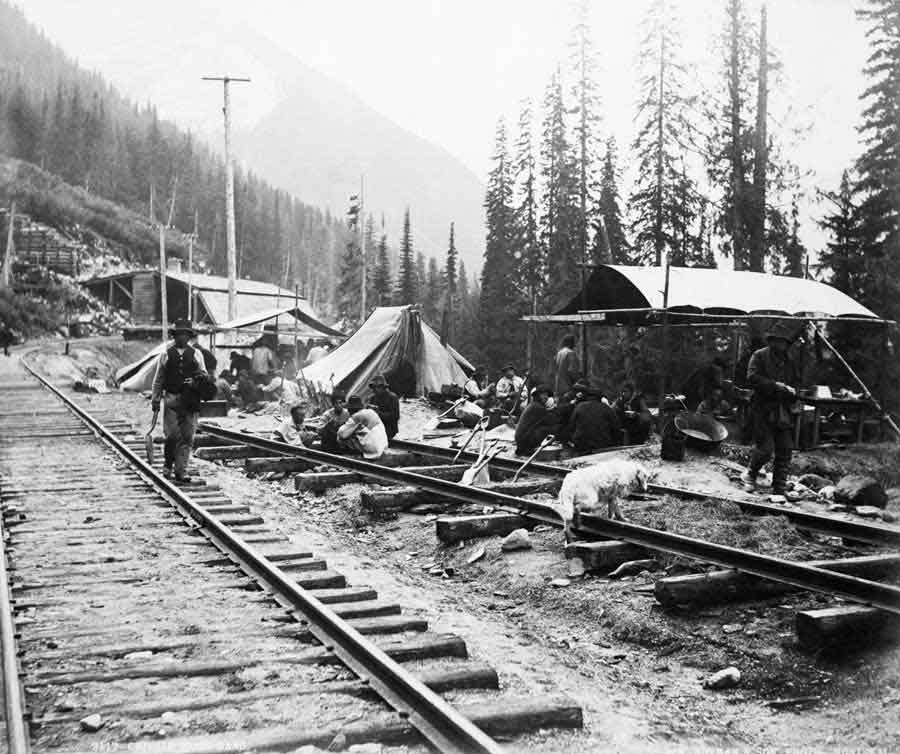

The construction of Canada’s railways created a great demand for workers. New immigrants from the British Isles, continental Europe and China made up much of the labour force on these projects. Railway construction also drew workers from local communities and the United States. Upon arriving in Canada, many immigrants encountered exploitative working conditions and poor living circumstances. This was the case for some 15,000 Chinese labourers who helped to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Working in harsh conditions for little pay, they suffered greatly and historians estimate that at least 600 died. (See also Immigrant Labour; Working-Class History.)

The Canadian Northern Railway

The flood of immigrants to the Prairie West after 1900 and the dramatic increase in agriculture soon proved the CPR inadequate, and a third phase of railway expansion began. Numerous branches sprouted in the West, of which the most notable was the Canadian Northern Railway, owned by the two bold entrepreneurs Donald Mann and William Mackenzie. The Canadian Northern grew by leasing and absorbing other lines; it also constructed new links to Regina, Saskatoon, Prince Albert and Edmonton, and pushed on through the Yellowhead Pass. It was linked to the East, with its main eastern terminus at Montreal, and also operated mileage in eastern Quebec and the Maritimes.

Though sometimes portrayed as rapacious promoters, Mackenzie and Mann built their railway to serve Western needs that were not being met by the CPR, and they invested most of their own fortunes in the enterprise. Nevertheless, the railway received public assistance of $250 million, most of it in the form of provincial and federal bond guarantees.

A Third Transcontinental Railway

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier enthusiastically encouraged the development of a third transcontinental railway by the Grand Trunk company, now led by Charles M. Hays. Although it would have made sense for the GTR to co-operate with the Canadian Northern company, mutual jealousies made such co-operation difficult. Therefore, the federal government itself decided to build a line from Winnipeg to Moncton (the National Transcontinental Railway or NTR) and to lease it to the GTR on completion. The NTR was built through the expanse of northern Quebec and Ontario in hopes of encouraging development there; begun in 1905, it was completed in 1913 at a cost of $160 million. The GTR’s subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific (GTP), constructed the more profitable line westward from Winnipeg. The GTP began construction in 1906 and was completed in 1914 through the Yellowhead Pass and along the spectacular Skeena River valley to Prince Rupert, BC.

Did you know?

In 1912, more than 7,000 immigrant workers on the Canadian Northern Railway and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway went on strike in British Columbia. Led by the Industrial Workers of the World, they demanded better living conditions in their work camps, including sanitation and a minimum wage. The workers’ demands were largely refused. The provincial government used violence and mass arrests to break the strikes. (See Fraser River Railway Strikes.)

Nationalization

The ill-planned proliferation of railways proved disastrous. Rumours of outrageous patronage in the building of the NTR were later confirmed. The Canadian Northern and GTP were constantly begging aid from the public purse. The First World War delivered the knockout blow, ending immigration and stifling the flow of British capital. In confusion and frustration, Prime Minister Robert Borden called a royal commission, headed by Sir Henry Drayton and British financier W.M. Acworth, which in May 1917 recommended the nationalization of all railways except the CPR. By the 1920s, the Canadian Northern, Intercolonial, Grand Trunk Railway and Grand Trunk Pacific were brought together to form the Canadian National Railways (CNR).

Did you know?

In the first decades of the 20th century, the job of sleeping car porter was one of the few positions available to Black men in Canada. Sleeping car porters were railway employees who attended to passengers aboard sleeping cars. While the position carried respect and prestige for Black men in their communities, the work demanded long hours for little pay. Porters could be fired suddenly and were often subjected to racist treatment. Black Canadian porters formed the first Black railway union in North America (1917) and became members of the larger Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1939. Both unions combatted racism and the many challenges that porters experienced on the job.

The North

The period after the formation of the CNR was essentially one of consolidation, although several lines were pushed into northern frontiers. The Hudson Bay Railway, beginning at a line built by Mackenzie and Mann to The Pas, Manitoba, in 1906, was finally opened to traffic in 1929. The Pacific Great Eastern began pushing slowly into the interior of BC in 1912. It was completed from Squamish to Quesnel by 1921, and finally reached Prince George and Dawson Creek in the 1950s. Northern Alberta Railways (owned jointly by CNR and CPR) ran lines from Edmonton North to Grande Prairie and to Dawson Creek by 1931.

Perhaps the most successful of these ventures was the Ontario Northland Railway, which reached James Bay in 1932. Owned by the Ontario government, the railway led directly to a mining boom in the Timmins-Porcupine area as well as to the emergence of the giant pulp and paper industry. The Quebec, North Shore and Labrador Railway, completed in 1954, provided access to the massive iron-ore deposits of interior Quebec and Labrador. The Great Slave Lake Railway was opened in 1964 between Roma, Alberta, and Hay River, Northwest Territories.

Challenges

More recently, railways have faced challenges from other modes of transportation. This has prompted significant changes at both the Canadian National Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway, including the privatization of CN in 1995 and the streamlining of operations at CP. Both railways are important carriers of bulk commodities in North America, particularly coal and grain. Many finished goods are also transported by rail, using railway containers that can easily be transferred between train, ship, and truck. Due to the relatively low cost of rail transport, rail is a cost-effective option for the long-distance transport of Canadian and American goods to market.

However, passenger travel has declined significantly. In order to compensate railways for the loss of passenger fares, the Canadian government offered direct subsidies to the railways from 1967 to 1977. This ended with the creation of VIA Rail in 1977, which became a Crown Corporation in 1978. VIA is responsible for most intercity passenger operations. In the 2000s, financial pressures led to the reduction of intercity service, although VIA still operates many passenger trains in the Quebec City–Windsor corridor.

Legacy

Did the railways achieve the ends expected of them? Did they repay the large infusions of public money? A final accounting can likely never be done, particularly in terms of judging the satisfaction of nationalistic and long-term economic goals. Regulation of the railways (now the responsibility of the Canadian Transportation Agency) and freight-rate agreements (notably the Crow’s Nest Pass Agreement) have been highly controversial, and very different views have been taken by western farmers and the railway companies on these issues (see Transportation Regulation).

At the same time, the railwaymen — from Fleming and Van Horne to Allan, Mann, Mackenzie, Stephen and Lord Shaughnessy — have been among the most prominent figures in Canadian history, evoking by turns admiration for their outstanding engineering feats and contempt for their perceived bleeding of the public purse.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom