Political Context

In the late 1950s and the early 1960s, several organizations were established to promote or achieve Québec independence. Some of them, such as the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale (RIN; see Pierre Bourgault) also tried their luck in the province’s political arena. On 13 October 1968, a political party was founded that was to continue to have an impact on Québec and Canadian politics for many years to come. The Parti Québécois, created by the merger of the Mouvement souveraineté-association, led by René Lévesque, and the Ralliement national, led by Gilles Grégoire, also received the support of the militant base of the RIN, which was dissolved at about the same time. As a new, pro-independence political party, the Parti Québécois soon became the rallying point for almost all nationalist movements and associations in Québec.

After enjoying moderate success on the political scene, the Parti Québécois won the Québec general election of 15 November 1976, defeating the Liberals under Robert Bourassa. This victory was attributable to a political manoeuvre, carefully orchestrated by Claude Morin, in which the party promised that it would hold a referendum on sovereignty-association during its first term in government.

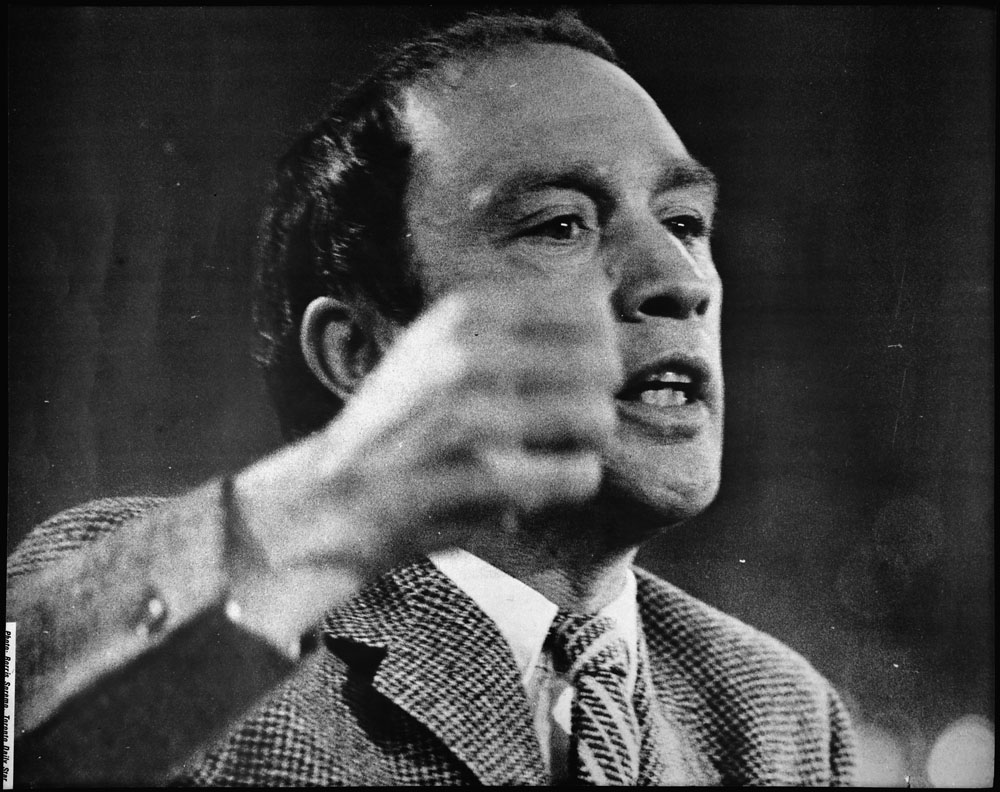

On 22 May 1979, the federal Liberal Party, led by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, lost the Canadian general election. René Lévesque would now be dealing with a federal minority government led by Joe Clark, a prime minister who had little influence in Québec. Thus conditions had at last become favourable for the date of the referendum to be announced. On 21 June 1979, René Lévesque told Québec’s National Assembly that the referendum would be held in the spring of 1980. In November 1979, the PQ government published La nouvelle entente Québec-Canada (known in English as the White Paper on Sovereignty-Association), in which it asserted that “sovereignty is indissociable from association.” The wording of the referendum question was announced on 20 December 1979:

The Government of Quebec has made public its proposal to negotiate a new agreement with the rest of Canada, based on the equality of nations; this agreement would enable Quebec to acquire the exclusive power to make its laws, levy its taxes and establish relations abroad — in other words, sovereignty — and at the same time to maintain with Canada an economic association including a common currency; any change in political status resulting from these negotiations will only be implemented with popular approval through another referendum; on these terms, do you give the Government of Quebec the mandate to negotiate the proposed agreement between Quebec and Canada?

In the meantime, in early December, the political calculus had changed again, when Joe Clark’s government lost a vote of confidence on its first budget. New federal elections were set for 18 February 1980. This time, the Liberals won, taking 74 out of 75 ridings in Québec, and Pierre Trudeau — who had returned as party leader — now formed a majority government ( see Elections of 1979 and 1980 ). He promised that his government would reform federalism and that a No vote in the upcoming Québec referendum would not be a vote for the status quo.

Results of the Referendum

When the referendum was held on 20 May 1980, the plan for sovereignty-association was rejected by 59.56% of the votes cast, with a participation rate of 85.61%. An estimated 50% of francophone voters had supported this option. Some observers attributed part of this support, especially among women, to a clumsy comment by Lise Payette, Parti Québécois Minister of State for the Status of Women. In a speech in the National Assembly on International Women's Day (8 March 1980), she had decried the stereotypical character of Yvette, who still appeared in Québec elementary school readers as the good little girl who helped around the house. At a partisan meeting the following day, Payette said that Claude Ryan, the leader of the No camp, wanted women to remain “Yvettes,” and she then insulted his wife by saying that he was married to one. Liberal Party activists wasted no time in exploiting the minister’s blunder. They held a massive “Brunch des Yvettes” in Québec City, followed by several others, including one in Montréal that attracted over 15,000 female supporters of the No camp. The “Yvettes” movement may well deserve credit for reversing the initial trend that showed 47% in favour of the Yes option.

In the days following the referendum defeat, the Parti Québécois reaffirmed that sovereignty was still the only viable option for Québec and would one day win majority support. This hope was already palpable in the speech that René Lévesque gave on the night after the referendum, when he said, “If I have understood you correctly, you are telling us, ‘until the next time.’”

Constitutional Talks Resume

In the aftermath of the referendum, intensive negotiations took place between the federal government and the 10 provincial governments (see also Constitutional History), but were suspended when the provincial representatives rejected the federal proposals to patriate the Canadian Constitution. Later, all of the provinces except Québec embraced this idea.

In April 1981, despite its loss in the referendum, the Parti Québécois was re-elected, with 80 seats in the National Assembly and 49.2% of the votes (an increase of more than 8% in popular support compared with the election of 1976).

Constitutional Accords Rejected and Second Québec Referendum Held

In September 1984, a Conservative federal government was elected, led by Brian Mulroney, and constitutional discussions between the federal and Québec governments resumed. In May 1985, the Parti Québécois announced the conditions that the government of Québec would require in order to support patriation. They included recognition of Québec’s distinct status and its right to either veto federal-provincial agreements or to opt out of them with adequate financial compensation if they were reached without Québec’s consent (see Federal-Provincial Relations).

The talks continued beyond the December 1985 Québec general election, in which Robert Bourassa’s Liberals were returned to power. In June 1987, an agreement was reached. Known as the Meech Lake Accord, it recognized Québec as a “distinct society,” comprised other constitutional changes as well, and was conditional on approval by the House of Commons and the provincial legislatures. At the end of the day, the agreement (see Meech Lake Accord: Document) was not adopted.

In October 1992, a Canada-wide referendum was held on another agreement, the Charlottetown Accord (see Charlottetown Accord: Document). This agreement was rejected by 54.3% of the voters. In October 1995, a Parti Québécois government held another referendum on Québec sovereignty (see Québec Referendum (1995)), which the No side won by a very slim majority: 50.58% of the votes. The participation rate was also very high: 93.25% of all Quebecers participated in this democratic exercise.

As of this writing, some two decades since this second referendum, the achievement of political sovereignty for Québec is still part of the program of the Parti Québécois. A second party in Québec’s National Assembly, Québec Solidaire, has also taken a position in favour of the principle of sovereignty for Québec.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom