Geography

Prince Edward Island is part of the Appalachian region, one of Canada’s seven physiographic regions. The island extends for 224 km, with a width ranging from 4 to 60 km. It’s surface ranges from nearly level in the west to hilly in the central region, and to gently rolling hills in the east. The highest elevation is 142 m in central Queens County.

The island’s predominant reddish brown sandy and clay soils are occasionally broken by outcroppings of sedimentary rock. This sedimentary rock is usually red-coloured sandstone or mudstone. The heavy concentrations of iron oxides in the rock and soil give the land its distinctive reddish-brown hue.

The coastline is deeply indented by tidal inlets. The north shore of the island, facing the Gulf of St. Lawrence, features extensive sand-dune formations. The shoreline generally alternates between headlands of steep sandstone bluffs and extensive sandy beaches. Dredging tidal runs created many of the island's harbours. These harbours are usable only by vessels of shallow draught, such as inshore fishing boats. A few harbours, such as those of Summerside, Charlottetown, Georgetown and Souris, provide access and shelter for larger vessels.

Little is left of the province’s original forests. Three centuries of clearing for agriculture and shipbuilding, as well as fire and disease, have radically transformed them. During the 19th century, the upland areas of the province were forested with beech, yellow birch, maple, oak and white pine. Today, many of these woodlands have deteriorated into a mixture of spruce, balsam fir and red maple. (See also Geography of Prince Edward Island.)

History

The first inhabitants of PEI were ancestors of the Mi’kmaq. There is evidence they occupied sites on PEI as many as 10,000 years ago by crossing the low plain now covered by Northumberland Strait. Occupation since that time has most likely been continuous, although there are some indications that there may have been seasonal migrations to hunt and fish on the Island as well. The Mi’kmaq have inhabited the area for the last 2,000 years.

Exploration

The first European to record seeing the Island was Jacques Cartier, who landed at several spots on the north shore during his explorations of the gulf in the summer of 1534. Although there was to be no permanent settlement for almost 200 years, the harbours and bays were known to French and Basque fishermen, but no trace of their visits has survived.

Settlement

French settlement of the Island (then known as Île St-Jean) began in the 1720s. The colony was originally a dependency of Île Royale, although a small garrison was stationed near what is now Charlottetown. Settlement was slow, with the population in 1748 reaching just over 700. However, with increasing British pressure on the Acadian inhabitants of Nova Scotia culminating in the decision to expel them in 1755, the population of the Island was significantly increased. Some 4,500 settlers were on the Island at the fall of Louisbourg in 1758, but the British quickly forced all but a few hundred to leave, even though the colony was not ceded to them until the Treaty of Paris (1763).

Under the British administration the name of the Island was anglicised to the Island of Saint John. This was the first of the new possessions to benefit from a plan to survey all of the territory in North America. Surveyor General Samuel Holland was able to provide detailed plans of the Island by 1765. He divided it into 67 townships of 20,000 acres each. Almost all of these were granted as the result of a lottery held in 1767 to military officers and others to whom the British government owed favours.

With the exception of small areas surrounding the land allotted for towns, there was no crown land. The proprietors were required to settle their lands to fulfil the terms of their grants, but few made an effort to do so. As a result the Island had vast areas of undeveloped land, yet those who wished to open up farms often had to pay steep rents or purchase fees.

Some proprietors refused to sell land at all and settlers found that they had no more security of tenure than they formerly had as tenants in England or Scotland. Further, the costs of the administration of the Island were to be borne by a tax paid by the proprietors on the land they held. This was often impossible to collect, and efforts made by the local government to enforce the terms of the grants were usually overruled by the British government under the influence of the landowners, most of whom never set foot in the colony.

The land question was the dominating political concern from 1767 until Confederation. Confrontation between the agents of the proprietors and the tenants frequently led to violence, and attempts to change the system were blocked in England. During the 1840s the government was able to buy out some of the landowners and make the land available for purchase by the tenants, but funds available for this purpose were quickly exhausted.

In spite of these difficulties the population grew from just over 4,000 in 1798 to 62,000 around 1850. Although there was an influx of Loyalists after the American Revolution, the majority of the newcomers were from the British Isles. Several large groups were brought from Scotland in the late 1700s and early 1800s by landowners such as Captain John MacDonald and Lord Selkirk, and by 1850 the Irish represented a sizable proportion of the recent immigrants.

Colonial Government

After 1758 the Island was administered from Nova Scotia and later, in 1763, became part of that province. In 1769, however, following representations made by the proprietors, a separate administration was set up complete with governor, lieutenant-governor, council and assembly. In 1799 the name of the colony was changed by the assembly to Prince Edward Island to honour a son of King George III stationed with the army in Halifax at the time.

With rapid growth in the second quarter of the 19th century, demands came for more effective control over the affairs of the colony by the elected assembly. Although the concept of representative government had been accepted since 1773, the administration was still dominated by the appointed executive council. In 1851 responsible government was granted to the colony and the first elected administration under George Coles took office. The period was not a politically stable one, however, for in the next 22 years, a total of 12 governments were in office. The land question continued and, in addition, matters such as assistance to religious schools divided the population.

Confederation

The Charlottetown Conference of 1864, the first in a series of meetings leading to Confederation, was held in the colony, and it marked the beginning of a period of political change that would leave a deep imprint. The meeting was called to discuss maritime union, but when visiting representatives from Canada began to promote a larger union, the original proposal failed to capture the imagination of Islanders.

When the other British North American colonies joined the new federation in 1867, few people in PEI regretted not being part of the union. The reluctance of the Islanders, however, could not last for long. A massive debt incurred by the Islanders in building a railway running from one end of the colony to the other, combined with pressures from the British government and Canadian promises, pushed the Island into Confederation in 1873. (See also Prince Edward Island and Confederation.)

The enticements offered by the Canadians included an absorption of the colony's debt, year-round communication with the mainland, and the provision of funds with which the colony could buy out the proprietors and end the land question. Although few Islanders displayed much enthusiasm, most accepted the union as a marriage of necessity.

Post-Confederation

The post-Confederation period brought severe hardships to the Island's economy and population as new technology, the National Policy and other forces combined to reduce the Island's prosperity. Although the province reached a population level of 109,000 in 1891, the lure of employment in western and central Canada, and in the US led to a drain on the population, which had slipped to 88,000 by the time of the Great Depression. Dominion-provincial relations dominated the political sphere as the Island sought to increase its subsidy from Ottawa, retain the level of political representation it had enjoyed at Confederation, and finally establish the continuous communication with the mainland that was promised in 1873.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the economy of the province was stable, with only slight changes in both farming and fishing — with the notable exception of the fox-farming industry between 1890 and 1939. By the mid-1960s, however, the situation had changed considerably. The number of farmers and fishermen had dropped, and the economy, which had lagged behind the rest of Canada, was in serious trouble.

Due to recent booms in PEI’s natural resource industries, the province has experienced several decades of relative stability. Important, however, are the continuing efforts to bring in new industry while still maintaining elements of the province’s history and heritage.

People

The Mi’kmaq can trace their ancestry on the Island as far back as 10,000 years ago. Upon the arrival of the Europeans, they were left with small parcels of land of poor quality, and suffered from disease and high unemployment. Late in the 20th century and into the 21st, PEI’s total Indigenous population slowly began to grow. They accounted for 0.7 per cent of the province’s population in 1996, 1 per cent in 2001, and approximately 1.3 per cent in 2006.

The majority of the Acadian population can be traced to several hundred Acadians who escaped deportation at the time of the British occupation of the Island following the fall of Louisbourg in 1758. In 2021, approximately 5.5 per cent of PEI’s population claims Acadian descent.

English, Scots and Irish arrived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and by 1861 the population of the Island grew to just over 80,000. Thereafter growth slowed and following 1891, natural increase was unable to keep up with the number of Islanders leaving, especially for New England.

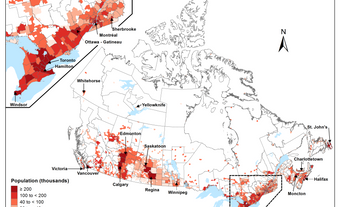

Most of the other ethnic groups on PEI are the result of immigration in the last 50 years. The 1950s and 1960s were periods of slow population growth as Islanders continued to leave the province in search of economic opportunities elsewhere. In-migration in the 1990s, combined with natural increase, caused the population to grow to 136,200 in 1996. In 2021, PEI’s population was 154,331, representing an 8 per cent increase from 2016. Despite this growth, the population only represents about 0.4 per cent of the Canadian total.

Urban Centres

As with other provinces, PEI’s urban population steadily increased throughout the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, but at a much slower rate than seen in most other provinces. Between 2001 and 2006, PEI’s urban population grew by only 0.8 per cent while its rural population declined by 12.8 per cent. Nevertheless, 62.9 per cent of PEI’s population dwelled in urban areas as of 2021.

PEI’s capital city, Charlottetown, is also its largest, with a population of 38,809 in 2021. Growth in the capital region has been most notable in the suburbs, but the city’s population grew by 7.8 per cent between 2016 and 2021.

Charlottetown is the seat of most government offices, the provincial university, the Confederation Centre of the Arts and the art gallery. At one time the city was a major port, but in recent years the number of vessels entering has declined significantly, although efforts by several agencies have resulted in regular visits by summer cruise liners. In 1984, the federal Department of Veterans Affairs was moved to the city, resulting in an increase in federal government employees in the area.

The next largest urban centre is Summerside. Summerside's principal economic bases are agricultural service industries and government offices.

Reserves

There are four reserves on Prince Edward Island, held by two First Nations. Three of these reserves, Morell, Rocky Point and Scotchfort, are held by Abegweit First Nation, while Lennox Island is held by Lennox Island First Nation. Both First Nations are Mi'kmaq. Of PEI’s 1,405 registered Mi'kmaq (2021), 615 live on the four reserves. The reserves vary in size from less than 1 km 2 to 5.4 km2. (See also Reserves on Prince Edward Island.)

Labour Force

In 2021, the sectors employing the most people on PEI were health care and social assistance, retail trade, and public administration.

Male and female employment rates are approximately equal, but unemployment across the province is a chronic problem. The unemployment rate in PEI is among Canada’s highest, at 10.3 per cent in 2021.

Language and Ethnicity

Along with Canada's Eastern Arctic, PEI is one of the most culturally homogeneous regions in Canada. The overwhelming majority of the Island's population (86.9 per cent) reported English as their mother tongue in the 2021 census, while only 3.0 per cent of the total population reported French. The most commonly reported ethnic origins were Scottish, Irish, and English. Visible minorities comprise 9.5 per cent of the population, with Chinese, South Asian, Filipino and Black people making up the largest visible minority communities. Indigenous people (including First Nations, Métis and Inuit) make up 2.2 per cent of the population.

Religion

Christianity is PEI’s central religion, with about 67.5 per cent of residents identifying with a Christian denomination, according to the 2021 census. Until recently religion played an important role in Island life. In 2021, about 28 per cent of residents claimed no religious affiliations.

Economy

Geography has dominated the economic history of PEI. In the 18th and 19th centuries its insularity was a benefit. Produce and manufactured goods had to travel only short distances before they could be loaded aboard cheap water transportation and the forests of the Island provided the resources for shipbuilding, which became a major industry in the mid-1800s. The prosperity of the Island was further reinforced by the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 that led to increased export of agricultural products to the US.

At the time of Confederation trade links were well established along the Atlantic seaboard and with the United Kingdom. However, the shift of focus after 1873 towards central Canada and western expansion, together with changes in technology, left the Island — which was a relatively strong economic partner in Confederation — in a weakened condition that has persisted to this day.

PEI was not prepared for the industrial age. It lacked coal and water resources essential to industrial development, and the cost and availability of transportation proved to be a difficulty not easily overcome. Industries on the Island were soon crushed by larger and more efficient plants in central Canada, but at the same time the National Policy provided no protection or markets for the Island's natural products.

The change in technology was most strongly felt in the shipbuilding industry. As the wooden sailing ship was replaced by steam vessels constructed of iron and steel, the entire industry died, having neither the raw materials nor the capital to make such a fundamental shift.

One activity in which the Island did provide a successful lead was in fox farming. Beginning in 1890 with the work of industry pioneers Charles Dalton and Robert Oulton, the province became the centre of a lucrative silver fox pelt industry. Fox breeding became very widespread, with many Island farmers supplementing their limited income from traditional agriculture in this way.

By the late 1930s new technology, changing fashions and the Great Depression caused a rapid decline in the industry. Several fox farms survived into the postwar period, but have since steadily declined. Although there was more stagnation in the economy than an absolute decline, by the early 1950s the per-capita income in PEI was just over half the national level and the outlook for the future was bleak.

The post-Second World War development of what amounted to new national policies had the most profound impact on the Island. Income support programs, human-services programs and new federal-provincial fiscal policy dramatically altered the Islanders' way of life. Attempts to alleviate regional disparities by using forced economic growth have caused a social revolution. Despite personal income levels remaining below the national average, these government programs helped increase income and provide markedly better health and educational facilities. The Federal-Provincial Comprehensive Development Plan, begun in 1969, has been central to much of this development.

This new period of development through government intervention also had negative consequences. Increasing dependence has been the principal cost. Recently, government initiatives have focused on further developing PEI’s natural resources and tourism in addition to attempting to diversify the Island’s economy by including new and more technological industries.

Agriculture

Agriculture is one of the province’s most important industries, and potatoes the most important crop.

In the latter half of the 20th century there were major changes in agriculture on Prince Edward Island. As late as 1951 over 90 per cent of all farms on PEI had horses, for a total of 21,000 animals. By 2011, only 1,481 horses and ponies inhabited the island, and fields used to produce the huge amount of forage for these animals have been turned to other uses.

The number of farms has steadily declined over the last 60 years. Between 1951 and 1996 the number of farms dropped from 10,137 to 2,217, and further dropped to 1,495 in 2011. While the number of farms has decreased, in the 20 year period between 1987 and 2007 the average size increased 53 per cent, from 238 acres to 365 acres. Despite the size of their properties, net farm income (about $3.1 million in 2012) is becoming a smaller portion of total income earned for PEI farmers. In 2006, for example, 43 per cent of farmers reported off-farm income.

Total farm cash receipts in 2012 were $467 million, representing an increase of 26 per cent since 2002. Of this total the most profitable single crop was potatoes, which earned over $246 million. Potatoes flourish in the soil and climate conditions found in PEI. The province is the nation's largest supplier of potatoes and the second-largest supplier of seed potatoes. Table stock is either sold fresh in eastern Canada and the US, or processed into French fries and other potato products. Dairy farms and beef production also represent a significant portion of PEI’s agricultural sector.

The provincial and federal governments have put in place a large number of programs to halt the exodus of farmers from the industry and to increase farm incomes. They have had some success, but the high cost of entering the industry remains a problem. At the same time, the average age of farmers has increased from 48 years in 1997 to 51 years in 2007. Both levels of government are active in agricultural research and Agriculture Canada maintains a large research facility in Charlottetown. The Atlantic Veterinary College on the campus of the University of Prince Edward Island has a significant impact on both animal and aquatic research benefiting the fishing industry.

Industry

Tourism, construction, primary resource-related manufacturing and services are the major industries of PEI. Since 1945, through exploiting the appeal of PEI's unspoiled landscape and sandy beaches, tourism has emerged as a major industry, growing significantly in the last three decades. However, it has sometimes brought inappropriate and random development, dependence on low seasonal wages and loss of land to off-Island owners. In 2000 the island attracted about 1.2 million tourists who spent over $301 million. By 2010 this number had increased slightly to over 1.3 million, generating $370 million in revenue. The completion of the Confederation Bridge in 1997 greatly increased tourist visits.

Since the 1960s, the government has been deeply involved in the construction and operation of attractions and accommodations. However, the major attraction remains the fine, warm sandy beaches along the 1,107 km of shoreline. Golf, deep-sea fishing and horse racing are among the sports available for tourists. Golf is particularly well-funded and recently gained much attention through exposure on the Golf Channel. In the last decade, government and private developers have established a number of heritage attractions, including sites operated by the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation. New cruise terminals, online reservation systems, improvements to provincial parks and active marketing campaigns have all helped to increase tourist traffic to the island in recent years. Attempts have been made to divert tourists from the central part of the Island, which is dominated by Prince Edward Island National Park, to eastern and western parts of the province, which have benefited less from the tourist dollar. A major problem is the shortness of the season, which consists of only eight to 10 weeks in July and August.

Mining

Mineral resources have not been discovered in commercial quantities on the Island, although trace deposits of coal, uranium, vanadium and other minerals exist. Since 1940, drilling has revealed the existence of natural gas beneath the seabed off the northeast part of the province, but its full natural gas supply is unknown because only exploratory wells have been drilled. Mining to date has been restricted to open-pit removal of gravel, but the latter is of low quality and in insufficient quantities to meet even local demand. Sand mining was a prevalent along PEI’s beaches until 2009, when the Department of Environment, Energy and Forestry stopped issuing sand mining permits. A study linking sand mining to the erosion of coastal beaches prompted the decision. As of 2008, PEI has opted to develop energy initiatives over its mining sector.

Forestry

Forestry is relatively undeveloped on the Island because of the depleted state of the woodlands and lack of effective management of the remaining resource. It was a principal industry in the 1800s, when most of the best timber was harvested. Since then forests have regenerated in species of little commercial value. Today, forests are being reconsidered as a source of both fuel and lumber for provincial use. Many Island homes are now being heated, at least in part, by wood fuel. Recent tax exemptions and financial incentives for wood heating systems helped re-establish wood and wood pellets as viable heat systems on the island.

Fisheries

Fishing is one of the most important resource sectors on the Island. The total value of fish landings (i.e. catch brought ashore) increased by about 37 per cent from 2009 to 2012, from $124.6 million to $170.4 million.

Lobster is by far the most valuable species. In 2012, the landed value of lobster was $113.8 million, more than double the value of other shellfish, including scallops and oysters, which accounted for $45.4 million in 2012. Pelagic and estuarial fish (e.g. Arctic char), as well as groundfish such as cod, are also caught in the Island’s waters.

Historically, another important industry in the western part of the Island was the harvesting of Irish moss, a marine plant that, when processed, yields carrageenan, an emulsifying and stabilizing agent used in many food products. However, the industry is steadily declining.

Transportation

Transportation to and from the Island by sea is currently handled by two ferry systems. Northumberland Ferries Ltd, a private company heavily subsidized by the federal government, operates between Wood Islands, PEI, and Caribou, Nova Scotia, from May to December, closing when ice and weather become severe. The second ferry service, C.T.M.A, runs from Cap-aux-Meules, Îles-de-la-madeleine to Souris, PEI.

Getting to and from the Island also takes place via Confederation Bridge, which links PEI to New Brunswick. It opened in May 1997 and at 12.9 km, it is the world's longest bridge over ice-covered water. The bridge is curved to keep drivers alert and reduce accidents, and the average crossing takes about 10 minutes. Discussion about the bridge began in earnest in 1987, when proposals for constructing a fixed link in the form of a bridge or tunnel came forward from the federal government and private developers. In January 1988, a plebiscite was held on the question by the provincial government of Premier Joe Ghiz. In this controversial vote, 59 per cent of Islanders voted in favour of a fixed link. Construction took four years and cost a total of $1 billion.

Over the years, the road network within the province has been substantially improved and now almost all primary and secondary routes are paved, which has greatly increased the use of road transportation in the shipping of primary and manufactured products. Additionally, the province is connected to major Canadian centres by daily air routes operated by West Jet and Air Canada.

Energy

Energy costs are one of the most serious problems facing PEI. Because the Island has only small ponds, few significant rivers, and generally low elevation, water power is seldom used. In the last century, numerous gristmills and sawmills used the limited hydropower available, but few survive today. Lacking hydroelectric capability, the Island is forced to rely on fossil fuels to generate power and on electrical power transmitted from New Brunswick via submarine cable. As of 2012, 76 per cent of PEI’s energy supply was from imported oil and almost half a billion dollars is spent annually on imported energy sources.

Since there is no potential for large-scale hydroelectrical development, alternative energy sources such as wind, solar and wood-fired generators are being investigated. In 2012, wind energy accounted for roughly 18 per cent of PEI’s energy supply while biomass accounted for another 10 per cent.

Provincial Government

There are 27 seats in Prince Edward Island’s provincial government. Each seat is held by a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) elected by eligible voters in their electoral district. According to the Elections Act, provincial elections are to be held on the first Monday of October, every four years. Sometimes, should the party in power see it as advantageous, an election may be called before this date. Elections may also occur before four years have passed in cases where the government no longer has the confidence of the Legislative Assembly (see Minority Governments in Canada).

As with the other provinces, PEI uses a first past the post electoral system, meaning the candidate with the most votes in each electoral district wins. Typically, the party with the most seats forms the government, and the leader of this party becomes premier. However, a party with fewer seats may also form a coalition with members of another party or parties in order to form the government.

Technically, as the Queen’s representative, the lieutenant-governor holds the highest provincial office, though in reality this role is largely symbolic. (See also Premiers of Prince Edward Island: Table; Lieutenant-Governors of Prince Edward Island: Table.)

The premier typically appoints members of the Cabinet from among the MLAs belonging to the party in power. Cabinet members are referred to as ministers and oversee specific portfolios. Typical portfolios include finance, health and education. (See also Politics on Prince Edward Island.)

Health

The Island is reasonably well served by hospital and health facilities, especially since the introduction of a provincial health-care plan in the late 1960s providing non-premium medical and hospital services. There are seven hospitals in the province, the largest hospital being the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Charlottetown. As in other provinces, health-care costs have risen sharply. A comprehensive ground ambulance system was established in 2006 and two rapid response units have recently been established to better serve rural Islanders. Air ambulance service is provided by Nova Scotia and New Brunswick when patients require immediate transportation.

Education

The public school system originated in the Free Education Act of 1852, and authorized the establishment of autonomous school districts based on local communities. Each of the 475 districts was entitled to a one-room school; usually offering grades one through 10. The school districts were governed by local boards, which collected taxes, hired teachers and organized volunteer services. Along with the church and the general store, schools became focal points in each community.

This system served the Island well in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but began to show serious deficiencies by the 1920s and 1930s. Inadequate facilities, lack of opportunities to study beyond grade 10 (except for a fortunate few who could attend high school in Charlottetown) and poorly paid, under qualified teachers all began to reach public attention. By 1956 per-capita expenditures for elementary and secondary education were the lowest in Canada — $92 compared with the $279 Canadian average — and by the 1960s the local schools, while providing an essential focus of community life, had fallen far behind Canadian educational norms.

The Comprehensive Development Plan provided the vehicle and the rationale for transforming the Island educational system. Beginning in 1972 the many small school districts were replaced by five regional boards, and the process of closing schools and building new, consolidated institutions began. In 1971 there were 189 schools; by 1994 that number had declined to 70. New regulations requiring university degrees for teachers were introduced, and teachers' salaries rose from an average of $5,724 in 1971 to $41,199 by 1994. As of 2011, most teachers in PEI could expect to earn between $47,135 and $76,289 annually.

During the 2011–12 school year, 20,831 students were enrolled in public school system. This is over a 10 per cent decrease from 10 years earlier, when 23,449 were enrolled in 2001–2. This is not a new trend: enrollment has been decreasing since the mid-1970s, due in large part to low birth rates and an aging population.

While enrollment is decreasing, spending is not. In 2009–10, $10,425 was spent per student in grades one through 12, up from $7,607 in 2004–5, an increase of 37 per cent. Also of note: full-day kindergarten was introduced in 2010; and during the 2011–12 year, PEI had the lowest teacher to student ratio in Canada.

Higher education in PEI began with the creation of Prince of Wales College (1834) and St Dunstan's University (1855). These two institutions were small and separated along religious lines. In 1969 they merged to form the University of Prince Edward Island, located in Charlottetown. Holland College is the Island’s community college.

Cultural Life

The rich cultural heritage of PEI developed as an integral part of the community partially because of the relative isolation of the province. Even within the province there was little communication between the Acadian communities in the western part of the Island and the predominantly Scottish communities in the southeast. Although the French language and Acadian culture have been strengthened in recent years, the Gaelic language has all but disappeared. Because of threats to the cultural life of the province, many groups actively support aspects of the Island's cultural heritage.

The provincial government assists these groups and funds a wide variety of activities. The Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, for example, not only administers historic sites but is also active in collecting and interpreting material culture. The Prince Edward Island Council of the Arts also assists and encourages local cultural development. Both Holland College and the University of Prince Edward Island are vital contributors to the contemporary cultural life of the Island.

Arts

The Confederation Centre of the Arts was built as a memorial to the Fathers of Confederation in 1964 to mark the 100th anniversary of the Charlottetown Conference. The centre is a major arts complex with three theatres, an art gallery and a public library. The gallery has a fine collection of Canadian art and features a large collection of the works of Robert Harris, a portraitist of the late 19th and early 20th century whose most notable work is the group portrait of the Fathers of Confederation. The 1,100-seat main stage theatre is home to the Charlottetown Summer Festival, a showcase of Canadian musical theatre.

At present there is an active artistic community on the Island and in addition to the Confederation Centre Gallery, there are several other private and public galleries. While the province is the home or birthplace of a large number of popular and academic writers, none is as well-known as Lucy Maud Montgomery, author of Anne of Green Gables. Most of Montgomery's stories are set on the Island and each year thousands of visitors come to see places mentioned in her books or associated with her life.

The Prince Edward Island Arts Guild officially opened in 1994. The building is the headquarters for many of the Island's arts organizations, including the Prince Edward Island Council of the Arts.

Communications

PEI is served by English-language CBC radio and by English- and French-language CBC television. The CTV television network also covers the Island, but is not produced locally. Four private radio stations broadcast in Charlottetown and one operates in Summerside. Cable television systems operate in all Island population centres, offering a wide range of programs, mostly of US origin.

There are two daily newspapers published in the province: the Guardian in Charlottetown and the Journal-Pioneer in Summerside. Three weekly papers are also published on the island: the Eastern Graphic, published in Montague; the West Prince Graphic, published in Alberton; and La Voix Acadienne, a French-language paper, produced in Summerside.

Historic Sites

Of Prince Edward Island's many important historic sites, the best known is Province House, the location of the Charlottetown Conference of 1864. Government House, the residence of the lieutenant-governor, is a carefully refurbished early 19th-century building. Other sites include Green Gables, the L.M. Montgomery home at Cavendish, and heritage sites operated by the Museum and Heritage Foundation at Charlottetown, Summerside, Elmira, Port Hill, Basin Head and Orwell Corner. A visitor can appreciate much of the Island's architectural heritage by simply walking in the older areas of Charlottetown or Summerside, or by driving along the country roads. Many fine examples of both rural and urban buildings from the last century are still intact and functional.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom