There are varying perspectives on when Indigenous peoples first arrived in what is now North and South America. Some Indigenous traditions state that Indigenous peoples have been here since time immemorial. Archaeological research ranges widely in arguments surrounding first arrival, including dates as far back as 130,000 years ago to as recently as 12,000 years ago.

First Indigenous Peoples in North America

There are numerous perspectives within the field of archaeology regarding the first arrival of Indigenous peoples to North America. Some archaeologists argue people may have arrived in North America as far back as 130,000 years ago. Others argue that the first human occupants of Canada arrived during the last Ice Age, which began about 80,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. During much of this period almost all of Canada was covered by several hundred metres of glacial ice. The amount of water locked in the continental glaciers caused world sea levels to drop by more than 100 meters, creating land bridges in areas now covered by shallow seas. One such land bridge crossed what is now the Bering Sea, joining Siberia and Alaska by a flat plain more than 1,000 kilometers wide (see also Beringia). This plain allowed for the movement of large herbivores such as caribou, muskox, bison, horse and mammoth, and, at some time during the ice age, these animals were followed by human hunters who had adapted their way of life to the cold climates of northern latitudes.

There is ongoing debate regarding the time of the first Indigenous peoples arriving in what is now Canada. It was long thought that humans could not have reached the American continents until the end of the ice age. That's because it was thought that before the last major ice advance, 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, human cultures in other parts of the world had developed neither technologies capable of living in the cold Arctic conditions of northeast Asia, nor watercraft capable of crossing the open seas of a flooded Bering Strait.

Recent research indicates, however, that humans had reached Australia across a wide stretch of open sea by at least 30,000 years ago, and that as long as 200,000 years ago the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) occupants of Europe were living under extremely cold environmental conditions and may have had watercraft capable of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. It is possible, therefore, that humans could have reached North America from northeast Siberia at any time during the past 100,000 years. Additionally, recent work by scholars, including some notable Indigenous scholars, argues that there is evidence indicating Indigenous peoples may have been living on the continents of North and South America as long ago as 130,000 or even 200,000 years ago.

Early Indigenous Peoples History

During the past few decades, several American continent archaeological sites have been claimed to date to the period of the last ice age. The earliest time frame for when Indigenous peoples may have lived in the continents of North and South America is actively debated within the field of archaeology. The earliest widespread occupation of the Americas that is universally accepted by archaeologists, however, begins 15,000 years ago. Much of Alaska and Yukon remained unglaciated throughout the ice age, probably because of a dry climate and insufficient snowfall (see also Nunatak). As such, these regions, called Beringia, were joined to Siberia by the Beringian Plain and separated from the rest of North America by glaciers. The environment was a cold tundra, although spruce forests were present at least during interstadial or nonglacial periods and supported a wide range of animals.

Archaeological finds along the Old Crow Basin in northern Yukon have been claimed by some researchers to indicate the presence of Palaeolithic hunting populations in the period 25,000 to 40,000 years ago. However, other archaeologists argue these objects have been found in redeposited sediments. As such, they argue many of them may have been manufactured by things other than humans (such as carnivore chewing or ice movement). Additionally, there are archaeologists that question the age of the few definitively man-made artifacts found in these locations.

Bluefish Caves is a broadly accepted archaeological site that shows occupation by humans in the Americas in north Yukon. Here, in three small caves overlooking a wide basin, a few chipped stone artifacts have been found in layers of sediment containing the bones of extinct fossil animals, which radiocarbon dating indicates are from between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago (see also Geological Dating).

The artifacts include types similar to those of the late Palaeolithic of northeast Asia and probably represent an expansion of hunting peoples from Asia across Beringia and Alaska into northwestern Canada. Archaeologists do not know whether people similar to those who occupied the Bluefish Caves expanded farther into North America. A relatively narrow ice-free corridor may have existed between the Cordilleran glaciers of the western mountains and the Laurentide ice sheet extending from the Canadian Shield, or, such a corridor may have opened only after the glaciers began to melt and retreat about 15,000 years ago (see also Glaciation).

Recent evidence suggests that another route may have been taken along the Pacific coast to the west of the Cordilleran glaciers. No early sites have been found along the route of these corridors, but by 12,000 years ago some groups had penetrated to the area of the western United States and had developed a way of life adapted to hunting the large herbivores that grazed the grasslands and ice-edge tundras of the period.

Expansion Across Canada

By about 11,000 years ago, some early Indigenous peoples began to move northward into Canada as the southern margin of the continental glaciers and the ice sheet retreated. Environmental zones similar to those found today in Arctic and subarctic Canada shifted northward as well. In many regions, the ice front was marked by huge meltwater lakes (e.g., Lake Agassiz). Their outlets were dammed by the glaciers to the north, and they were surrounded by land supporting tundra vegetation grazed on by caribou, muskoxen and other herbivores. To the south of this narrow band of tundra were spruce forests and grasslands, and the early Indigenous peoples probably followed the northern edge of these zones as they moved across Canada.

Archaeological sites related to early Indigenous peoples’ are radiocarbon dated to around 10,500 years ago in areas as far separated as central Nova Scotia and northern British Columbia. The largest sites yet found in Canada are concentrated in southern Ontario, where they are clustered along the southern shore of Lake Algonquin, the forerunner of the present Lake Huron and Georgian Bay (see also Great Lakes).

By about 10,000 years ago, early Indigenous peoples had probably occupied at least the southern portions of all provinces except Newfoundland. Most sites are defined by a scattering of chipped stone artifacts, among them spear points with a distinctive channel or "flute" removed from either side of the base to allow mounting in a split haft. Such "fluted points" are characteristic of early Indigenous peoples’ technologies from Canada to southern South America and serve to define the first widespread occupation of North and South America about 9,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Hunting Culture

Because very little organic material is preserved on archaeological sites of this period, it is difficult to reconstruct the way of life of early Indigenous peoples. In the dry western regions of the US, where sites are better preserved, they appear to have concentrated on hunting large herbivores, including bison and mammoths. In Canada, archeologists speculate that early Indigenous peoples hunted caribou herds of the east and the bison herds of the northern plains, as well as fishing and hunting small game. Coastlines were well below present sea level, so any evidence of early Indigenous peoples use of coastal resources has been destroyed by the later rise in sea level.

While early Indigenous peoples lived in southern Canada, the continental glaciers melted over the course of about 4,000 years and disappeared by about 7,000 years ago. A warmer climate existed until about 4,000 years ago, and the environments of the country diversified as coniferous forest, deciduous woodland, grassland and tundra vegetation became established in suitable zones. The ways of life of early Indigenous peoples living in these environmental zones became diversified as they adapted to the conditions and resources of local regions. The development over time of the various cultures of early Indigenous peoples is therefore best described on a regional basis.

West Coast

There is little evidence that the classic "fluted point" of early Indigenous cultures penetrated the coastal regions of British Columbia. The earliest occupants of the area appear to have been related to other cultural traditions. About 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, the southern regions were occupied by people of the Old Cordilleran tradition, whose sites are marked by pebble tools made by knocking a few flakes from heavy beach cobbles, and by more finely made lanceolate projectile points or knives chipped from stone. No organic material is preserved on these sites, but their locations suggest that these people were adapted primarily to interior and riverine resources, gradually making greater use of marine resources.

The northern and central coast was occupied by people of the early Coast Microblade tradition, who also used pebble tools but lacked lanceolate points. Microblades are small razorlike tools of flint or obsidian made by a specialized technique and were widely used during this period in Alaska and northwestern Canada. It is suggested that these people entered British Columbia from the north and that they were related to Alaskan groups who may have crossed the Bering land bridge shortly before it disappeared.

Salmon Fishery

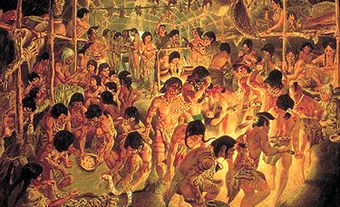

It is unclear how either of these two groups were related to those who occupied the West Coast after 5,000 years ago, but it seems likely that both contributed to the ancestry of the later Indigenous peoples. At about 5,000 years ago, a major change occurred in coastal occupation. Whereas earlier sites were all relatively small, indicating brief occupations by small groups of people, large shell middens, or human-made heaps, characterize most of the more recent sites.

Stabilization of sea levels probably resulted in increased salmon stocks, which in turn allowed people to store more food and live a more sedentary life in coastal villages that were occupied for years or generations. Animal bones and bone tools have been preserved in the shell middens, and artifacts of wood or plant fibre appear in occasional waterlogged deposits, allowing archaeologists to reconstruct a more complete picture of the way of life of these people than of earlier occupants of the region.

Artifacts recovered from the earliest sites indicate an efficient adaptation to the coastal environment. Barbed harpoons for taking sea mammals, fish hooks, weights for fish nets, ground slate knives and weapon points, and woodworking tools that could have been used for the construction of boats have been found on coastal sites of the period. Waterlogged sites have produced examples of basketry, netting, woven fabrics and wooden boxes similar to those known from the historic period. By about 3,500 years ago, there is evidence that this adaptation was beginning to lead to the development of the societies of the Northwest Coast.

Burials that show differential treatment in the number of grave goods for members of the community, as well as the appearance in some regions of artificial skull deformation, suggest the existence of the ranked societies with which these practices were later associated. The high incidence of broken bones and skulls among male burials, coincidentally with the appearance of decorated clubs of stone or whalebone, suggests the development of a pattern of warfare.

Art Objects

Social organizations based on status and wealth may also account for the appearance at this time of numerous art objects, personal ornaments such as beads, labrets and earspools, and exotic goods indicating widespread trade networks into the interior and to the south (see also Indigenous Art).

A similar situation appears to have characterized most coastal regions during the past 1,500 years. This interpretation is based on the decline of the sculpted stone artwork that characterized the preceding period, perhaps indicating only a change from art in stone to art in wood and woven fabrics, which are poorly preserved archaeologically but were highly developed by the later Indigenous peoples of the region. This period produces the first definitive evidence for occupation of the large plank-house villages characteristic of the historic period, and of major earthworks and defensive sites indicating an increase in warfare. Stone pipes mark the introduction of tobacco. The people of the past 1,500 years developed the various traditions and ways of life of the Northwest Coast Indigenous Peoples.

Intermontane Region

The valleys and plateaus of interior British Columbia are characterized by diverse environments ranging from boreal forests through grasslands to almost desert conditions. The early Indigenous cultures of the area were correspondingly diverse, and this variety, combined with the lack of sufficient archaeological research in the region, results in an unclear picture of this time in the area.

Earliest Canadian Skeleton

Archaeological finds of early Indigenous peoples’ projectile points and other artifacts indicate that the earliest peoples of the area came from the plains, adapting their grassland bison-hunting way of life to the pursuit of bison, wapiti and caribou in the intermontane valleys. Little is known of these people, but the skeleton of one man who died in a mudslide near Kamloops is radiocarbon dated to about 8,250 years ago and is thus the earliest well-dated human skeleton known from Canada. Analysis of the composition of the bones indicates that this man lived primarily on land animals rather than on the salmon of the Thompson River.

Between 8,000 and 3,000 years ago, the area appears to have been occupied by various groups who manufactured and used microblades and who are thought to have been related to the microblade-using peoples of the north coast or of the Yukon interior. The riverine location of many microblade sites suggests that these groups were developing adaptations based on the salmon resources of interior rivers, but little else is known.

Pit House Villages

A major change in the occupation of the region began about 3,000 years ago, with the introduction of semi-subterranean pit houses from the Columbia Plateau to the south. Pit house villages grew larger through time, indicating a more efficient economy and an increasingly sedentary way of life. Around this time, in the coastal areas to the west, archeological sites show evidence of exotic trade goods (shells), stone sculpture and differential burial patterns. Over the past 3,000 years, cultural influences from the West Coast, the plains and the Columbia Plateau combined to form the cultures of the various interior peoples of British Columbia (see also Indigenous People: Plateau).

Plains and Prairies

The northern plains and prairies of western Canada, like no other region of North America, provided an environment in which the descendants of early Indigenous peoples of 10,000 years ago were able to continue their way of life until the time of European contact. As the large herbivores of the ice age became extinct in the early postglacial period, these people transferred their pursuit to the various species of now-extinct bison that occupied the grasslands. Although heavily dependent on bison, early Indigenous peoples and their later descendants must also have been hunters of smaller game and gatherers of plant foods where available. They almost certainly developed techniques of communal hunting involving ambush or the driving of bison to hunters armed with spears and darts thrown with throwing boards. Archaeology knows these people primarily through the chipped flint spearpoints that they used.

New Hunting Methods

By about 9,000 years ago, their fluted projectile points had been replaced by lanceolate or stemmed varieties characteristic of the late Plano people. Between approximately 9,000 and 7,000 years ago, the Plano people developed a widespread and efficient bison-hunting adaptation across the northern plains. By at least 7,000 years ago, caribou hunters using spearpoints obviously related to those of the Plano tradition had pushed northward to the Barren Lands between Great Bear Lake and Hudson Bay.

The following two millennia on the northern plains, between approximately 7,000 and 5,000 years ago, are poorly known. This period saw the climax of the postglacial warm period or altithermal, and it is suggested that heat and drought reduced the carrying capacity of the grasslands so that the area was occupied by fewer bison and consequently by fewer bison hunters.

Sites around the fringes of the plains, and some sites in the plains area itself, show continuing occupation, and the development of spearpoints with notches for hafting. Such points are characteristic of approximately 5,000 to 2,000 years ago, during which various groups developed more efficient communal bison-hunting techniques, including the use of pounds and jumps, over which the bison were driven (see also Head-Smashed-In-Buffalo-Jump).

Technology From Outside

Over the past 2,000 years, the plains area was introduced to various influences from the Eastern Woodlands and from the Mississippi and Missouri valley peoples to the south. During the early first millennium CE, small, chipped stone arrow points began to replace the spearpoints of earlier times, and the introduction of the bow increased hunting efficiency. Pottery cooking vessels and containers of types similar to those in use to the east and south were used. Burial mounds were constructed in some regions, especially in southern Manitoba (see also Linear Mounds Archaeological Site), and exotic trade goods indicate contacts with the farming people of the Missouri Valley. Although most of the northern plains was beyond the limit of early agriculture, relatively small-scale farming was attempted in the more southerly regions.

Horses Arrive on Plains

The westward push of European settlement in the 18th century caused a rapid acceleration of change in plains life, as peoples from the eastern woodlands began to move westward onto the grasslands. Horses, which had gradually spread northward from the Spanish settlements in the American southwest, reached the Canadian plains about 1730, causing a revolution in Indigenous techniques of hunting, travelling and warfare, until the near extinction of the bison as a result of European settlement in the late 19th century.

Eastern Woodlands

Early Indigenous hunters using fluted spear points lived in southern Ontario, and probably the St. Lawrence Valley, by at least 10,000 years ago when the ice sheet had retreated from the area. With the draining of the large ice-edge lakes and seas of the region, the extinction of the ice-age fauna, and the establishment of coniferous forests, the environments of these regions changed dramatically during the following two millennia. The next occupation of the region was by later early Indigenous peoples using artifacts similar to those of the Plano tradition, which developed on the plains to the west.

The best evidence for Plano occupation comes from the northern shores of lakes Superior and Huron, but Plano-related sites are known from the upper St. Lawrence Valley and as far east as the Gaspé Peninsula. These eastern Plano people of some 9,000 to 7,000 years ago were probably big-game hunters who were heavily dependent on caribou, the predominant herbivore in the subarctic forests of the period.

Archaic Cultures

Around 7,000 years ago, warmer climates and the establishment of deciduous forests, saw the development of Archaic cultures. The Archaic label is applied to cultures throughout eastern North America which show adaptations to the utilization of local animal, fish and plant resources. These adaptations probably allowed increases in the populations of many areas, and greater social complexity is suggested by complex burial practices and the existence of long-distance trade. The Archaic stage is also marked archaeologically by the development of new items of technology: stemmed and notched spear points and knives, bone harpoons, ground stone weapon points and woodworking tools (gouges, axes), and in some areas, tools and ornaments made from native copper.

Early Indigenous peoples of the Shield Archaic culture lived in the Canadian Shield area of central and northern Quebec and Ontario. They apparently developed about 7,000 years ago out of northern Plano cultures such as those which occupied the Barren Grounds west of Hudson Bay, or those known from northwestern Ontario. Since the acid forest soils of the region have destroyed all organic remains, relatively little is known of their way of life. From the locations of their camps, however, they were probably generalized hunters heavily dependent on caribou and fish. Although pottery and other elements were introduced from the south about 3,000 years ago, marking the Woodland period of local history, it seems likely that the way of life present during the Archaic period remained relatively unchanged and was much like that of the Algonquian peoples of this area at the time of European contact and the beginning of the fur trade.

The deciduous forest areas to the south supported denser populations than the spruce forests to the north and saw the development, about 6,000 years ago, of the Laurentian Archaic, probably from earlier Archaic cultures of the area. These people were generalized hunters and gatherers of the relatively abundant animal and plant resources of the region. Exotic materials such as copper and marine shells, most often found as grave goods in an elaborate burial ceremony, indicate extensive trade contacts to the south, east and west.

Introduction of Farming

The appearance of pottery, introduced from areas south of the Great Lakes between 3,000 and 2,500 years ago, is used archaeologically to mark the beginning of the Woodland period. As in the regions to the north, the initial Woodland period probably saw few changes in the general way of life of local peoples. During the following centuries, however, there is evidence of continuing and expanding influence from the south, including an elaborate mortuary complex involving mound burial, which appears to have been transferred, or at least copied, from the Adena and Hopewell cultures of the Ohio Valley (see also Rainy River Burial Mounds). The most important introduction was agriculture, based on crops that had been developed in Mexico and Central America several millennia previously, and which had gradually spread northward as they were adapted to cooler climatic conditions

The first crop to appear was maize, or corn, which began to be cultivated in southern Ontario about 1,500 years ago and was a major supplement to a hunting and gathering economy. The early maize farmers occupied relatively permanent villages of multifamily wood and bark houses, often fortified with palisades as protection from the warfare that appears to have intensified with the introduction of agriculture. By 1,350 CE beans and squash were added to local agriculture, providing a nutritionally balanced diet that led to a decrease in the importance of hunting and gathering (see also Indigenous Peoples: Uses of Plants).

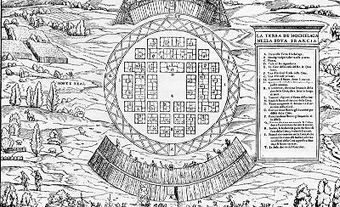

Pre-colonial Iroquoian Villages

At the time of European contact, this agricultural lifestyle was characteristic of the Iroquoian peoples who occupied the region from southwestern Ontario to the middle St. Lawrence Valley. It is the only region of Canada in which early agriculture was established as the local economic base and was the area with the greatest Indigenous population density.

The Iroquoian peoples lived in villages composed of large multi-family longhouses, with some of the larger communities containing more than 2,000 people. Wide-ranging social, trade and political connections spanned their area of occupation.

East Coast

Early Indigenous peoples lived in what are now the Maritime provinces by at least 10,000 years ago, but evidence of their presence is slight as sea levels were much lower than at present and only traces of interior camps can be found above present sea level. The same problem restricts knowledge of early Archaic sites, although archeologists assume that there was continuous occupation throughout this period, as there was in the Eastern Woodlands area to the west.

Marine Hunting Tools

The best evidence of early Archaic occupation is found in the Strait of Belle Isle area of Labrador where initial occupation occurred before 8,000 years ago and is marked by chipped stone artifacts suggesting a later early Indigenous peoples/Archaic transition. The coastal location of these early Archaic sites suggests a maritime adaptation, an interpretation reinforced by the 7,500-year-old mound at L'Anse Amour Site in which was found a toggling harpoon, a walrus tusk and an artifact of walrus ivory. The term Maritime Archaic is applied to these people and their descendants.

Coastal hunting and fishing allowed Maritime Archaic people to expand to far northern Labrador by 6,000 years ago, and to Newfoundland by about 5,000 years ago. For the following 2,000 years they were the primary occupants of these areas, developing a distinctive maritime way of life with barbed harpoons, fishing gear, ground-slate weapons and ground-stone woodworking tools.

Maritime Archaic people also elaborated a mortuary complex in which large cemeteries were used over considerable lengths of time, the burials accompanied by large numbers of grave goods and heavily sprinkled with red ochre. Cemeteries of this type are found in the Maritime provinces and New England. Similarities in burial traditions, artifacts and the physical type of the skeletons suggest relationships to the contemporaneous Laurentian Archaic of the Eastern Woodlands, and it seems likely that Laurentian people occupied some regions of the Maritime provinces.

Migration from the North and East

Between 4,000 and 2,500 years ago, the Maritime Archaic people were displaced from most of coastal Labrador by a southward expansion of Palaeo-Inuit from the Arctic, and by other Archaic groups moving eastward from the Shield area and the St Lawrence Valley. The Dorset culture people also occupied Newfoundland for about a millennium, beginning about 2,500 years ago. With the withdrawal of the Palaeo-Inuit from Newfoundland and all but northern Labrador about 1,500 years ago, these areas were re-occupied by people who were probably ancestral to the Labrador/Innu and Newfoundland Beothuk. Archeologists do not know whether these were the descendants of earlier Maritime Archaic people, or of other groups that moved to the area at a later time.

Trade and Cultural Influences

In the Maritime provinces to the south of the Gulf of St Lawrence, the past 2,500 years saw the introduction of ceramics from the south and the west. The possible extent of other cultural influences is suggested by the 2,300-year-old Augustine burial mound in New Brunswick, which duplicates the Adena burial ceremonialism of the Ohio Valley and includes artifacts imported from that region. Early in this period local groups apparently began to develop a more sedentary way of life, as shell middens began to accumulate in some coastal regions. Evidence from these sites indicates a generalized hunting and fishing way of life, utilizing both coastal and interior resources. This lifestyle was characteristic of Atlantic Canada at European contact, and the sites dating to the past 2,000 years almost certainly represent those of the ancestral Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqiyik peoples.

Western Subarctic

The forest and forest-tundra area between Hudson Bay and Alaska is, archaeologically, one of the least-explored regions of Canada. Although the far northwest of the region has produced evidence of extremely early human occupation, later developments are only vaguely known.

In the area to the west of the Mackenzie River, there is thought to be evidence of two distinct early postglacial occupations dating between 11,000 and 7,000 years ago. One is by groups related to early Indigenous peoples of more southerly regions and marked by lanceolate spear points. Probably the earliest Indigenous peoples to live in the area used fluted points since a few such artifacts are known from Alaska and Yukon. However, these finds have not been dated earlier than the fluted point sites to the south, so it is still uncertain whether they represent the original movement of early Indigenous peoples to the south or a subsequent return movement northward.

Somewhat more recent occupations are marked by spear points which relate either to the late Plano tradition of the northern Plains, or to the Old Cordilleran tradition of British Columbia and the western US. The second major occupation is by groups related to the Palaeoarctic tradition of Alaska.

It is unclear how these early occupations relate to those of the Northern Archaic, which was present in the area from about 6,000 to at least 2,000 years ago. This culture is characterized by notched spearpoints and other elements of apparent southern origin, but at least the early sites of the period also produce microblades, and microblades may have been in use in some regions until close to the end of this period. Neither is it known how the Northern Archaic relates to the ancestry of the Dene who occupied interior northwest Canada. Definite ancestral Dene sites can be traced for only about the past 1,500 years in this area. This may represent a movement of Dene from elsewhere or continuous development out of the Northern Archaic of earlier times.

The earliest occupation of the region between Mackenzie River and Hudson Bay was by Plano-tradition people who moved into the Barren Grounds from the south shortly before 7,000 years ago. Notched spearpoints and other types of stone tools from at least 6,000 years ago led to the definition of the Shield Archaic tradition. It seems that the Shield Archaic developed locally out of Plano culture, rather than representing a movement of people from the south, and there was little change in the way of life followed by local groups. The Barren Grounds continued to be occupied by Shield Archaic Indigenous peoples until about 3,500 years ago when, perhaps in response to climatic cooling that caused the treeline to shift southward, the region was taken over by Palaeo-Inuit from the Arctic coast (see also Climate Change).

This occupation lasted for less than 1,000 years, when people using various forms of lanceolate and stemmed spearpoints, and later arrow points, reoccupied the territory. The origin of these groups is not clear, but they probably moved into the Barren Grounds from the south and west and may have arrived at various times between 2,500 and 1,000 years ago. At least the more recent of these groups were ancestral to Dene, who led a caribou-hunting way of life not greatly different from that of the Plano and Shield Archaic peoples of much earlier times.

Arctic

The coasts and islands of Arctic Canada were first occupied about 5,000 years ago by groups known as Palaeo-Inuit. Their technology and way of life differed considerably from those of known Indigenous groups and more closely resembled those of eastern Siberian peoples. Although there is disagreement among archaeologists on the question of Palaeo-Inuit origins, it seems likely that the Palaeo-Inuit crossed the Bering Strait from Siberia, either by boat or on the sea ice, approximately 5,000 years ago, and rapidly spread eastward across the unoccupied tundra regions of Alaska, Canada and Greenland. These early occupants seem to have preferred areas where they could live largely on caribou and muskox but were also capable of harpooning seals and in some areas adapted to a maritime way of life.

Early Palaeo-Inuit technology, based on tiny chipped flint tools including microblades, was much less efficient than that of Inuit occupants of the region. There is no evidence that they used boats, dogsleds, oil lamps or domed snowhouses, as they lived through most or all of the year in skin tents heated with fires of bones and scarce wood. Nevertheless, between 4,000 and 3,000 years ago they occupied most Arctic regions and had expanded southwards across the Barren Grounds and down the Labrador coast, displacing other Indigenous occupants.

Dorset People

After about 2,500 years ago, the Palaeo-Inuit way of life had developed to the extent that it is given a new label, the Dorset Culture. There is some evidence that the Dorset people used kayaks and had dogs for hunting if not for pulling sledges; soapstone lamps and pots appear, as well as semi-permanent winter houses banked with turf for insulation. Dorset sites are larger than those of their predecessors, suggesting more permanent occupation by larger groups, and in some regions, it is apparent that the Dorset people were efficient hunters of sea mammals as large as walrus and beluga. A striking art form was developed in the form of small carvings in wood and ivory (see also Inuit Art). It was the Dorset people who, around 2,500 years ago, moved southward to Newfoundland and occupied the island for about 1,000 years.

Early Inuit

The Dorset occupation of Arctic Canada was brought to an end between 1,000 and 500 years ago, with the movement into the area of Early Inuit peoples from Alaska. Over the preceding 3,000 years, these ancestors of the Inuit, who were probably descended from Alaskan Palaeo-Inuit, had developed very efficient sea-mammal hunting techniques involving harpoon float and drag equipment, as well as kayaks and large, open skin boats from which they could hunt whales. The early Inuit movement across the Arctic, during a relatively warm climatic period when there was probably a decrease in sea ice and an increase in whale populations, occurred rapidly.

Travelling by skin boat and dogsled, by 1,200 CE, they had established an essentially Alaskan way of life over much of Arctic Canada and displaced the Dorset people from most regions. In Greenland and in the eastern Canadian Arctic, they soon came into contact with the Norse, who had arrived in Greenland about 980 CE. Norse artifacts have been recovered from several early Inuit sites (see also Norse-Indigenous Contact).

The early Inuit way of life, characterized by summer open-water hunting and the storage of food for use during winter occupation of permanent stone and turf winter houses, became more difficult after 1,200 CE as the arctic climate cooled, culminating in the Little Ice Age of 1600 to 1850 CE. During this period, many elements of their way of life had to be changed, and the early Inuit either abandoned portions of the Arctic or rapidly adapted to the new conditions. During the same period, contact with European sailors, whalers and traders (see also Basque, History of Commercial Fisheries), and the impact of European diseases may have been as important as climate change in altering the traditional early Inuit way of life. It was during this period that much of the culture of the Inuit was developed (see also Inuit).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom