A political campaign is an organized effort to secure the nomination and election of people seeking public office. In a representative democracy, electoral campaigns are the primary means by which voters are informed of a political party’s policy or a candidate’s views. The conduct of campaigns in Canada has evolved gradually over nearly two centuries. It has adapted mostly British and American campaign practices to the needs of a parliamentary federation with two official languages. Campaigns occur at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal levels. Federal and provincial campaigns are party contests in which candidates represent political parties. Municipal campaigns — and those of Northwest Territories and Nunavut — are contested by individuals, not by parties.

Historical Background

Political campaigns in Canada have a long history. Representative political institutions were established in the British North American colonies of Lower Canada, Upper Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick before the end of the 18th century. (See also Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Canadian Parliamentary Democracy.) Early campaigns preceded the creation of organized political parties. The campaigns were largely a series of individual efforts in local constituencies. (See also Local Government.)

Until responsible government was established in the mid-19th century, the governor of each colony, as the appointed representative of the British Crown, frequently intervened in electoral campaigns; they ensured the election of members who would co-operate with them and make the necessary funds available to their administration. Once responsible government was achieved, recognized government officials and opposition leaders attempted to coordinate the campaigns of their followers. The goal was to elect as many of them as possible.

With Confederation in 1867, campaigns had to be extended over a vast geographical area. The general election campaigns of 1867, 1872 and 1874 were conducted in a highly decentralized manner. They largely followed the rules and practices that the various provinces had inherited from pre-Confederation days.

Unlike their modern counterparts, early campaigns did not lead up to a single polling day. Elections were spread over several weeks. Different ridings voted on different days. This enabled the government to schedule the polling in its safest ridings at an early date. This created a bandwagon effect that might persuade voters in more doubtful ridings to support the incumbents. Opposition strongholds were left to the last so as not to discourage supporters of the government. Party leaders and other notable figures often were candidates in more than one constituency. This increased their odds of retaining a seat. (See also Voting in Early Canada.)

Within each riding, voting might extend over two days. Voting was by a show of hands rather than by secret ballot; bribery and intimidation were therefore a common and more-or-less accepted aspect of campaigns. (See Political Corruption; Conflict of Interest.) The small size of the electorates facilitated a more personal approach to campaigning than is possible today. Skilful politicians such as Prime Minister John A. Macdonald knew most of their supporters by name. In the federal election of 1867, an average of fewer than 1,500 votes was cast in each constituency.

First Modern Campaign

The federal election campaign of 1878 was in some respects the first modern campaign. Almost all candidates represented one of the two recognized parties: Liberal or Conservative. The parties were clearly differentiated on issues of policy. Their policy approaches were extensively discussed during the campaign. The Conservative victory was regarded as a mandate to implement that party’s policies of tariff protection and rapid completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Virtually all constituencies voted on the same day. A secret ballot was used for the first time. This was also the first election in which candidates were required to appoint an official agent and to file a statement of their campaign expenditures. The most important procedures followed in future campaigns were largely established in 1878. The first national election provisions were enacted in 1885. This laid the foundations for the present system. Canada’s electoral process is now national; the same basic rules are in force throughout the country.

Strategies

Modern electoral campaigns are carefully planned and coordinated efforts. They require lengthy preparation and centralized control. The leader of a party appoints a campaign committee with a campaign director reporting to the leader. Specific persons are responsible for various aspects of the campaign, including fund raising; advertising; travel arrangements; relations with the media; and the measurement of public opinion.

In the Liberal Party, it is customary to run a separate campaign in Quebec that reports directly to the national leader. This is because Quebec has its own political culture; it often has different priorities and issues than the rest of Canada, all of which are expressed through its own francophone news media. For the Conservative and New Democratic (NDP) parties, federal campaigns in Quebec were merely a part of the overall national effort until the mid-1980s. This changed for the Conservatives following their capture of a large majority of seats in Quebec in 1984. The NDP followed suit soon thereafter.

Campaign planning is somewhat easier for the party that controls the government. The prime minister normally determines the date of the election. It is selected to advantage the governing party’s campaign; or when the opposition is at a disadvantage. The date is influenced by prevailing economic conditions, by the government’s popularity and by the progress of its legislative program through Parliament. This important advantage is lost when an election is brought about by the loss of a vote of confidence in the House of Commons. In such cases (e.g., the federal elections of 1926, 1963 and 1980), the governing party loses this advantage. Since an election must be held at least every five years, a prime minister can also lose the advantage by letting the election take place on the pre-determined date.

Campaign strategies must also consider the varying loyalties to parties held by many Canadians. Each party seeks first to mobilize its own supporters (the party’s “base”). It then attempts to secure the votes of those who might be leaning in its direction. Finally, it tries to persuade as many undecided voters as possible. Governing parties stress their accomplishments in office and announce plans designed to attract undecided voters. Opposition parties attack the government’s record and make promises to do better if elected.

Campaign Issues

Campaign issues emerge out of the debate between the government and the Opposition. Issues sometimes emerge unpredictably and alter the political agenda (e.g., the Syrian refugee crisis during the 2015 election campaign). Not all campaigns are characterized by well-defined issues. Partly for this reason, and partly because Canadian parties are not sharply differentiated by ideology, campaigns emphasize the personal characteristics and capabilities of the party leaders. Parties try to acquaint voters with the leaders and to convince voters of their attractiveness; this often includes attacks on the leaders of other parties.

Examples of federal election campaigns that were dominated by a particular issue include those of 1878 (National Policy); 1891 (reciprocity with the United States); 1896 (Manitoba schools question); 1911 (reciprocity again); 1917 (conscription); 1926 (the constitutional powers of the governor general in the King-Byng Affair); 1957 (the government’s imposition of closure during the pipeline debate); 1963 (nuclear weapons); 1974 (wage and price controls); and 1988 (free trade with the United States).

Most of these issues were raised by the Opposition, rather than the government. Most of these campaigns ended with the defeat of the governing party. The 1988 campaign, in which the government sought and received a mandate to implement free trade, was an exception. Whenever the opposition parties failed to generate a major issue, the governing party was typically re-elected. The governing party usually prefers to emphasize its competence and overall record rather than a specific issue.

The issues of greatest importance to Canadians can change from election to election. Even the position of parties can change over time. For example, in 1911, the governing Liberals favoured a comprehensive reciprocal trade agreement with the United States. The Conservatives opposed it and won. Those positions were reversed in 1988.

During election campaigns, parties try to focus voters’ attentions on the issues where they are generally seen as most competent. It is this struggle to shape the criteria by which voters evaluate parties and leaders that defines elections.

Leadership

Campaigns typically emphasize the personality, charisma and traits of the leaders. This approach is often deplored by those who would prefer a more intellectual, policy-oriented approach to politics. This is nothing new, as former slogans attest: “The Old Man, The Old Flag, and The Old Party” (used for John A. Macdonald’s last campaign in 1891); “Let Laurier Finish His Work” (1908); “King or Chaos” (1935); and “It’s Time for a Diefenbaker Government” (1957). In each case, the leader referred to in the slogan won the election.

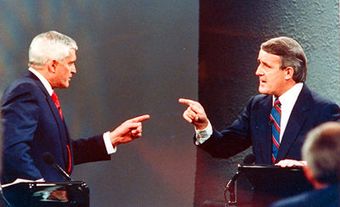

In earlier campaigns, the ability of the leaders and their image to influence the voters was largely indirect. It was dependent on the persuasive powers of local candidates and of newspapers that supported the leader. Today, thanks to modern transportation and communication — particularly televised debates — party leaders, or at least their public images, are much better known to voters.

In the early Canadian elections of the 19th century, John A. Macdonald and his Liberal opponents, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake, campaigned only in central Canada. Wilfrid Laurier, in 1917, was the first party leader to visit the Western provinces during a campaign. William Lyon Mackenzie King failed to visit Quebec, his party’s major stronghold, during his successful campaign in 1921.

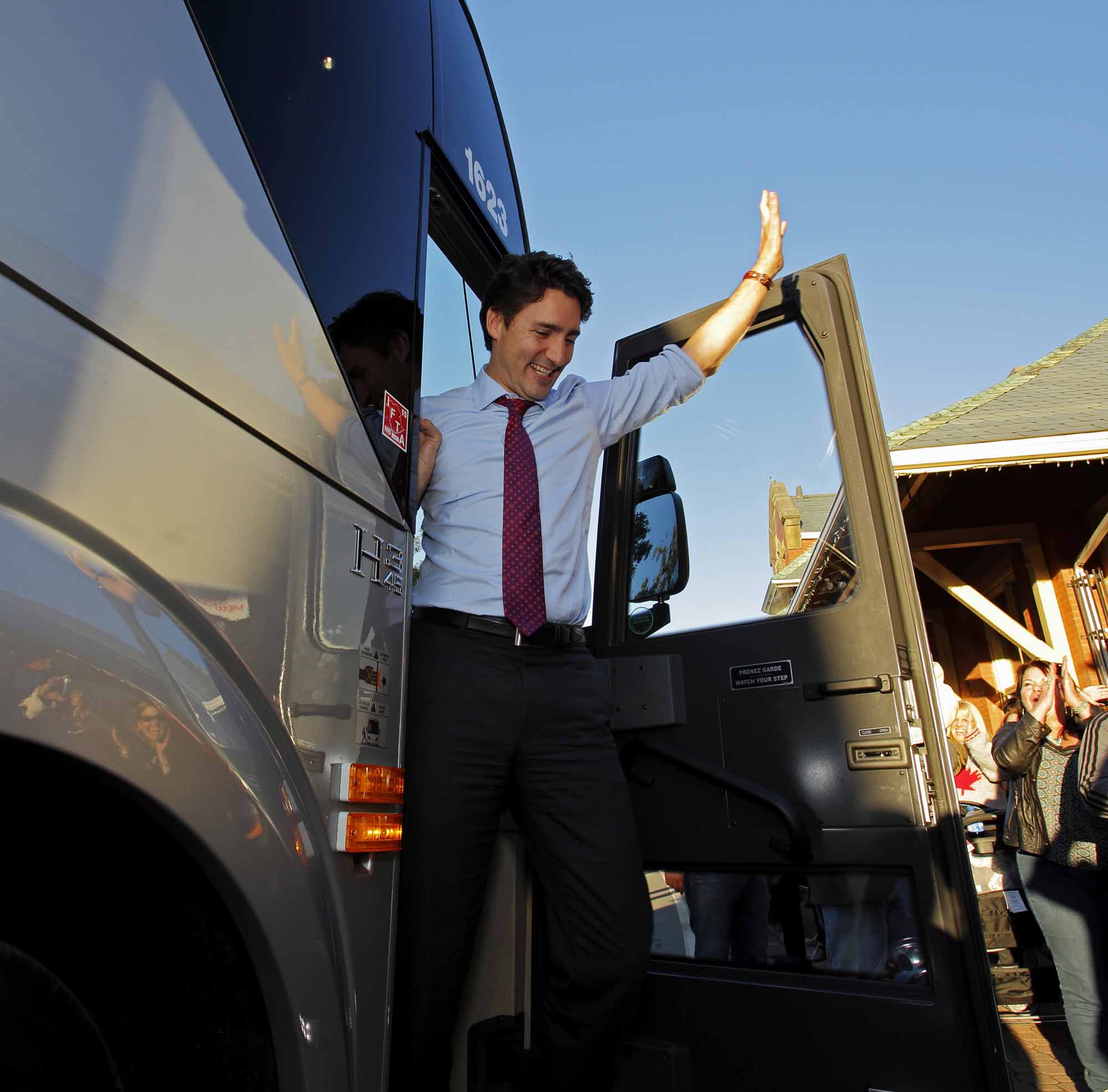

Today, leaders of national parties are expected to campaign in every province. Planning the leader’s schedule during the two months of the campaign is an important task. Party leaders who held office up to and including John Diefenbaker, relied mainly on the railways for their travel. Today’s leaders use chartered buses and aircraft, often emblazoned with their party logos. At each stop on the tour, the leaders promise new policies of particular interest to the locality.

Media

Electronic communications have made it possible for voters to hear and see party leaders without leaving their homes. Nationwide radio broadcasts by party leaders were first used in the federal campaign of 1930. Television was first used in the campaign of 1957. In the late 20th century, all-news cable television brought daily campaign events live into voters’ homes. It also shortened the news cycle from several days or weeks to a 24-hour period. In the 21st century, the Internet, cellular phones and social media allow campaigns to reach voters almost anywhere. Instant communications have also shortened the news cycle to a matter of hours.

Television and the Internet have made it unnecessary to attract large numbers of voters to political rallies. Party leaders still address large rallies in hockey arenas and auditoriums. But today, such events are attended mainly by reporters and people directly involved in the party’s local campaign. Those in the latter category are often brought to the rally by chartered bus to ensure that empty seats will not be seen by voters viewing the event on television or online. Perhaps no medium has done more than television to turn campaigns into contests of images over ideas. In modern campaigns, the leader that looks and sounds the most trustworthy and likeable on television, rather than the party with the best policy, often has the greatest advantage.

Advertising

Political advertising is now an essential part of any campaign. Modern advertising techniques were first applied to political campaigns before the Second World War. Today, advertising agencies are often employed year-round by political parties, not only during campaigns. They are highly influential in shaping campaign strategies and advising Canadian leaders. Slogans, leaflets, posters, lapel buttons and other paraphernalia, as well as newspaper advertisements and videos, seek to create the desired image of the party, its leaders and its policies. Most advertising expenditures by parties are now devoted to television.

Even policy development, and the ideas put forward by leaders and parties during a campaign, are often determined not by policy experts or politicians themselves; but by advertising and marketing advisors hired to shape the party’s brand and message. During a campaign, “message discipline” is imposed on a party’s candidates; often by strategists who operate in backroom offices and who might never be known to voters. Critics argue that as modern marketing and branding techniques have risen in importance; the authenticity of candidates and what they say has declined.

Negative advertising is as old as democracy itself; as are attacks that directly criticize or raise doubts about an opposing party and its leader. There is widespread debate in Canada about the appropriateness of attack ads. Some believe they turn off voters from the political process and suppress voter turnout on election day. Others say negative ads are a legitimate tool in campaigns. They are used for the simple reason that they work; by harming the electoral chances of the targeted candidate. Occasionally, negative ads backfire. One of the most spectacular examples of this was a television ad in the 1993 campaign. The Progressive Conservatives highlighted the facial deformity of Liberal leader Jean Chrétien, who has Bell’s palsy. The ad was roundly condemned. Chrétien was elected prime minister; the Conservatives suffered their greatest defeat ever.

Polling

Modern campaigning is also deeply affected by the sampling and measuring of public opinion. The periodic measurements of party standings by independent polling organizations are reported in the media. These may affect the timing of elections and create a bandwagon effect during the campaign. The parties themselves employ their own pollsters and polling firms (whose findings are normally not published) to identify areas of strength and weakness; to discover the voters’ attitudes towards leaders, candidates and issues; and to determine the particular image and brand of a campaign.

National War Rooms

Television and the Internet, air travel, and modern techniques of measuring and manipulating public opinion have all increased the importance of centralized organization in a national or provincial campaign. The heart of a modern federal campaign is its national headquarters. These are often based in Toronto or Ottawa. They comprise a team of strategists, advisors, advertisers, pollsters, logistics planners and media relations staff. They are led by a campaign manager or director and work in a campaign “war room.” They determine the daily message or announcement by the leader; react to statements by opposing candidates or special interest groups; and handle news media requests and messaging.

A second, smaller tier of advisers and planners travels with the party leader as he or she campaigns across the country. They remain in close contact with national headquarters. The national campaign office, in consultation with the leader’s group, gives strategic direction to a party’s campaign offices, and to local constituency campaigns.

Local Constituencies

Strong local campaigns at the constituency level are still necessary for electoral success. (See also Local Government.) Local campaigns are primarily the responsibility of the candidate, their official agent and the local campaign manager. The main objectives are to introduce the candidate to as many voters as possible; to identify the voters who are likely to support the candidate; and to ensure that those voters actually vote. The first objective is accomplished mainly by having the candidate visit voters at their homes. It is also customary to visit places where many voters are employed. Community associations in middle-class neighbourhoods often sponsor debates among the local candidates. However, it is widely believed that they are only attended by voters who have already made up their minds.

Identifying the committed vote was easy in the stable rural communities and small towns of Macdonald’s and Laurier’s Canada. Today, among the diverse and highly mobile populations of modern cities, it can only be accomplished by an army of party canvassers. They attempt to visit each household at least once during the campaign. On election day, they will check to ensure that friendly voters have actually voted. They may even provide transportation to the polling place.

Local campaigns, now generally honest and fair, were not always so. In rural areas, it was once common to bribe voters with food, alcoholic beverages and money. (See Political Corruption.) In the larger cities, such as in Montreal before the Quiet Revolution, there were many instances of impersonating voters; placing fictitious names on the voters’ lists; stealing ballots and intimidating the other party’s volunteers by the threat or use of violence. Stricter regulation of campaigns and a more affluent and sophisticated electorate have brought about the end of such practices. However, the manipulation of the electorate through advertising; the extensive branding and image-making of party leaders and candidates at the expense of authenticity; and the frequency with which campaign promises are ignored after the election, continue to raise questions about the quality of the democratic process.

See also Political Party Financing in Canada; Political Participation in Canada; Canadian Party System; Canadian Electoral System; Chief Electoral Officer; Electoral Behaviour.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom