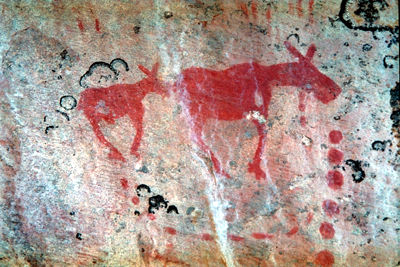

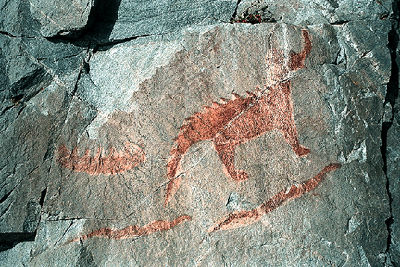

Rock art is generally divided in two categories: carving sites (petroglyphs) and paintings sites (pictographs). Pictographs are paintings that were made by applying red ochre or, less commonly, black, white or yellow dye. Although the majority of the images were traced with the finger, some could be executed with brushes made of animal or vegetal fibres. Petroglyphs are carvings that are incised, abraded or ground by means of stone tools upon cliff walls, boulders and flat bedrock surfaces.

Pictographs and Petroglyphs in Canada

Rock art sites have been discovered throughout Canada. In fact, pictographs and petroglyphs may constitute Canada's oldest and most widespread artistic tradition. It is part of a worldwide genre of rock art, which includes the cave paintings of Spain and France as well as the rock art of Scandinavia, Finland, northeast Asia and Siberia. No foolproof method for the precise dating of rock art has been discovered, other than speculative association with stratified, relatively datable archaeological remains. The tradition of rock art was no doubt brought into Canada by its earliest occupants during the last ice age.

Rock art in much of Canada is linked with the search for helping spirits and with shamanism - a widespread religious tradition in which the shaman’s major tasks are healing and prophesy, along with the vision quest. Several broad regions of rock art "style areas" have been distinguished, including the Maritimes, the Canadian Shield, the Prairies, British Columbia and the Arctic.

The Maritimes

The Maritime provinces count many rock art sites that are usually attributed to the Mi'kmaq. Essentially composed of petroglyphs, this art generally consists of fine incisions made on slate rocks along the shores of lakes and rivers. Some of them are found in Kejimkujik National Park, at Medway River and MacGowan Lake, and in southwest Nova Scotia. Images include animals, anthropomorphic figures, hunting and fishing scenes, footprints and fingerprints, and ornamental designs that are also found on Mi’kmaq clothes. In addition to this traditional iconography, there are also images of European origin, such as firearms, churches and Christian designs as well as beautiful representation of sailboats.

The Canadian Shield

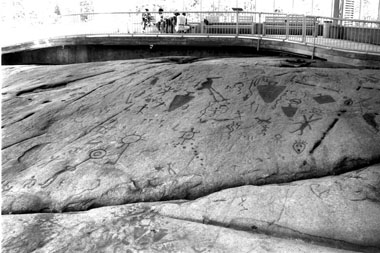

The Canadian Shield, which extends from Rivière St-Maurice in Québec to northern Saskatchewan, counts more than 500 pictograph sites, while petroglyph sites are confined to the south. The Peterborough petroglyph site in southern Ontario (see Petroglyphs Provincial Park) is the most outstanding in all of Canada with its several hundred images of humans, animals and boats, all contained on a single rock outcrop of crystalline limestone. Here, there are no pictorial boundaries such as frames or groundlines, and it seems that there is no deliberate grouping of images. Aesthetic order is in accord with nature, and images are often integrated with the numerous hollows, crevices and seams of the rock itself.

It has been showed that in painting sites, the arrangement of symbols corresponds to the ordering of the spiritual world in different levels: the Thunderbirds above, humans and other animals in the middle, and the underworld beings (the Horned Snake or Mishipeshu, the big lynx) at the inferior level. Moreover, the use of crevices, cracks or mineral seams (mostly quartz) shows an organization of space and a composition that stage the different mythological elements. For instance, the battle between Thunderbird and the Horned Snake is often depicted as the bird killing the reptile with lightning, which is materialized in the composition by a seam of quartz. Other iconographic themes also appear regularly: a figure with horns or rabbit ears accompanied by a wolf probably represents Nananbozo and his brother Wolf; a snake or Mishipeshu under a canoe shows the danger of those beings, which tip canoes and drown their passengers.

Pictograph sites in the Canadian Shield are less extensive in scale and contain fewer image clusters compared to carving sites. Although sites at Bon Echo Provincial Park in southern Ontario and at Lake Superior Provincial Park near Wawa, Ontario are well known, the majority of pictograph discoveries have been made in Quetico Park and at Lake of the Woods in northwestern Ontario. Hundreds of pictograph sites and a few petroglyph sites have been discovered in this part of the Canadian Shield, where they may have been in production from a very early period. At the site of Mud Portage in the Lake of the Woods area, for example, petroglyphs have been discovered beneath the layers of an Archaic period archaeological deposit, which have been dated by their discoverers to before 5,000 years ago, making them the oldest in Canada. Radiocarbon dating at the Nisula site along Lac Cassette, Québec, indicated that the paintings were made about 2,000 years ago. The geographic distribution of rock art sites and the iconographic themes that are represented seem to indicate that carvings and paintings on the rocks of the Canadian Shield were produced by the ancestors of Algonquian populations, including the Ojibwe, Cree, Innu and Anishinaabeg.

The Prairies

Despite the lack of rock surfaces on the Prairies, petroglyphs and pictographs are an important art form of southern Saskatchewan (see Saskatchewan Rock Art) and Alberta. The Herschel Site in Saskatchewan contains petroglyphs that could pertain to the oldest rock art tradition in North America, whereas the black paintings of the Swift Current Creek Site are unique in the country. Many pictographs have been found on isolated boulders and rocky outcrops along the foothills near Calgary. At Áísínai’pi (Writing-on-Stone) Provincial Park in southern Alberta, there is an extensive series of small-scale petroglyphs incised on the sandstone bluffs of the Milk River. They depict spiritual icons such as Thunderbird or shaman figures. Some narratives have also been illustrated: this is the case of a complex, four-metre long battle scene showing a camp circle, mounted warriors, tipis, guns and shot. The petroglyphs sometimes show evidence of contact with Europeans, since horses, men bearing guns and wheeled carts are found.

British Columbia

Some of the most intriguing images of Canadian rock art are painted on cliffs in interior British Columbia. Those near Keremeos are probably abstractions of the spirits the shaman encountered in his visions. The BC coast has many petroglyph sites, though the few pictograph sites are probably more recent. Stylistically, West Coast rock art is unique in Canada, often showing form and subject-matter linkages with the later historic art of the 19th century and with the very similar petroglyphs found on the lower Amur River in northeast Asia. Outstanding sites are located primarily on Vancouver Island - Nanaimo Petroglyph Park and Sproat Lake - but sites have been discovered as far north as Prince Rupert and along the Nass and Skeena River system.

The Arctic

The few rock art sites discovered in the Canadian Arctic are all located in the Kangirsujuaq area on Qikirtaaluk Island, Nunavik. They contain petroglyphs that only represent full faces, with human, animal or hybrid features. The carvings were probably made by the Dorset people, which occupied the Arctic between 500 BCE and 1500 CE. The faces that are found in rock art sites resemble masks that were sculpted by them. Among the sites recorded to this day, the most important is no doubt Qajartalik, which is located on the northeast side of the island, near the community of Kangirsujuaq. The site contains more than 170 faces that were incised in an outcrop of soapstone (steatite) about 1,500 years ago. Most of the faces are symmetrical and some have feline features and horns. The carvings probably had a spiritual meaning for the Dorset. Unfortunately, the Qajartalik petroglyphs have been vandalized several times.

Research History

Pictographs and petroglyphs in Canada were mentioned by explorers, travellers and settlers as early as the late 18th and early 19th centuries. But significant records and studies appeared only after 1850, initially by American scholars. The first to illustrate and interpret pictographs from the point of view of Indigenous peoples themselves was Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, a US Indian agent stationed at Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, in the early 19th century. He described the Agawa Pictographs at Bay near Wawa, Ontario, and wrote on the practice and meaning of pictography among Algonquian speakers in North America in a 6-volume publication dated 1851-57.

The work of Colonel Garrick Mallery for the Smithsonian Institute, however, was primarily responsible for stimulating scholarly and popular interest in rock art. His still definitive survey, Picture-Writing of the American Indians (1893), includes descriptions and drawings of several Canadian sites in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. In 1887 and 1888, Mallery visited and first recorded some of the extensive Kejimkujik petroglyphs in Nova Scotia.

Discoveries and accounts of rock art by Canadian authors appeared sporadically in the 1890s and more abundantly in the early decades of the 20th century. In BC, James A. Teit reported on pictographs of interior BC (1896-1930). In Ontario, David Boyle, one of Canada’s pioneer archaeologists, did most of the early rock art recording. He was notably the first, in 1896, to describe and illustrate the pictographs at Lake Mazinaw.

In these early years, too, Harlan I. Smith, archaeologist with the National Museum, wrote many of the earliest accounts of petroglyph sites along the BC coast (1906-36), following upon initial discoveries on Vancouver Island by the American anthropologist Franz Boas. While rock art research abated considerably across Canada between 1930 and the early 1950s, BC remained a focus of activity. Between 1936 and 1942, for example, Francis J. Barrow surveyed and reported on south coastal sites and the Norwegian archaeologist and rock art authority Gutorm Gjessing published 2 major studies of BC rock art after a cross-Canada survey undertaken in 1946-47.

In 1949, BC novelist and author Edward Meade began recording coastal petroglyph sites from Alaska to as far south as Puget Sound, the results of which appeared in 1971. Starting in 1960, the same territory was thoroughly covered by Beth and Ray Hill, whose lavishly illustrated book did much to attract public interest in BC rock art. In the province's interior, apiarist John Corner continued Teit's research. This work resulted in a popular illustrated survey, which remains a key publication for the region.

The 1960s were particularly rich years for rock art investigation in Canada, culminating with the foundation of the Canadian Rock Art Research Association (CRARA) in 1969. This national association of specialists devoted to research, public education and preservation of pictograph and petroglyph sites in Canada was instrumental in fostering public awareness and increased scholarly interest across the country through its biannual conferences and newsletters. Selwyn Dewdney was elected first senior associate in recognition of his long-standing contribution to rock art recording in the Canadian Shield and to public education. A commercial artist and art therapist, Dewdney had begun recording pictographs and petroglyphs for the Royal Ontario Museum in 1957. Aiming for a continuance of Boyle's pioneering work, Kenneth E. Kidd, then curator of ethnology, had sought funding for the systematic documentation of Ontario's rock art sites. With initial support of the Quetico Foundation, Dewdney was selected for the task of locating and recording new as well as forgotten sites in the rugged Shield. From 1957 to his death in 1979, Dewdney discovered and traced hundreds of sites throughout Ontario and westward to Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. The book co-authored by Dewdney and Kidd has stimulated enormous public interest in rock art of the Canadian Shield.

By the late 1960s, the scientific study of pictographs and petroglyphs had become widespread across Canada. More accurate systems of photographic as well as other means of recording have been applied and experiments have been undertaken, chiefly by scientists of the Canadian Conservation Institute, for the dating and preservation of unprotected rock art sites. Since the 1970s, a new generation of researchers and their students have continued to discover new sites and re-investigate known ones, using new methods of recording and new theories of interpretation.

Research has tended recently to focus on the interpretation of both the function and meaning of rock art in the context of Indigenous cultures and on the relationship of pictographs and petroglyphs to other forms of Indigenous visual expression. For about the last decade, research has shifted towards the study of the surrounding landscape and the integration of rock art sites in a broader geographical context (e.g., the importance of the area within the lakes or rivers network, the proximity of rapids or falls).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom