Parliament Hill is a nine-hectare (0.09 km2) site in downtown Ottawa. It is home to Canada’s Parliament Buildings, the seat of the country’s federal government. Parliament Hill’s open grounds — a rarity among national parliaments — provide a place to gather for celebration or protest and are a National Historic Site. An excellent example of the gothic revival architecture style, the Parliament Buildings — Parliament (Centre Block) and two office buildings (East and West blocks) — officially opened on 6 June 1866. The Library of Parliament is the only part of the original Centre Block to have survived a fire in 1916. A Memorial Chamber and Peace Tower were added to the rebuilt Centre Block in honour of fallen First World War soldiers. The Centennial Flame was added to the grounds to mark Canada’s centennial in 1967. A $4.5–5 billion project to restore the Parliament Buildings began in 2002 and is due to be finished by 2031.

Background and Function

Parliament Hill in Ottawa is a visually striking complex of buildings located on a limestone outcrop overlooking the Ottawa River. It was proposed after Queen Victoria chose the small town for the new capital in 1857. Construction of the Parliament Buildings began in 1859. They were to provide more extensive space for a House of Commons and a Senate.

The Parliament Buildings — comprising Parliament (Centre Block) and two administrative buildings (East and West blocks) — are set within a designed landscape in the picturesque tradition. The complex is also known as the Parliamentary Precinct.

The site was once used as living quarters for the Royal Engineers who worked on the Rideau Canal and was known at the time as Barracks Hill. It was considered the obvious choice for the location of the Parliament Buildings. The hill was a local public meeting site before the buildings were constructed. After their completion, people continued to visit the grounds in honour of special occasions, such as royal jubilees, state funerals and other significant events. Public protests and rallies were recorded as early as the 1870s. Regular organized protests became more common after the Second World War.

Parliament Hill’s open grounds are a rarity among national parliaments of the world. Vital to the Hill’s character today are both its celebrations, including annual Canada Day festivities and the ceremonial Changing of the Guard, and its role as a democratic forum for citizens. These functions combine to reinforce the Parliament Buildings as the centre and symbol of Canada's federal government.

Site Description

Parliament Hill is on an approximately nine-hectare (0.09 km2) site. It is both named and officially delineated by the Parliament of Canada Act. It lays between the Ottawa River in the north and Wellington Street in the south, from the Supreme Court of Canada building in the west, to the Rideau Canal in the east. Within the Precinct, the Centre Block and the Parliamentary Library are centrally located at the hill's highest point near a steep escarpment. The East and West Blocks are on each side of the Centre Block. They create a public plaza facing the city's urban core. Directly to the southeast lies the National War Memorial and the National Arts Centre. The Bank of Canada is across the street to the southwest.

Commemorative monuments of political and royal figures are found throughout the grounds. In 2000, Parliament's commemorative program widened to include an ensemble statue depicting the Famous Five women who spearheaded the Persons Case. The most notable monuments on the Hill were designed by prominent Canadian sculptors, such as Louis-Philippe Hébert, Walter Allward and Frances Loring.

The landscape of the grounds is distinctly different from the grid-like plan of central Ottawa. Its formal and informal areas create a picturesque landscape. The land surrounding the new buildings was neglected until 1873. New York-based landscape architect Calvert Vaux drew up plans for the grounds, though he never visited Ottawa. His plan for a rising, curving roadway with elegant staircases leading to a wide upper terrace unified the sloping stages between the street and the hill's highest point.

A scenic walkway along the edge of the rugged escarpment surrounding the formal grounds provides views across the Ottawa River out to the Gatineau Hills. The public can stroll the grounds and at one time had access to a "lovers' lane" down the hill's escarpment.

Competition to Design Parliament

At the time of Confederation, few building projects on as large a scale as the one proposed for the Parliament Buildings had been completed in Canada. A competition was held in 1859 to find suitable architects for three federal buildings: a Parliament building (Centre Block), two administrative buildings (East and West Blocks), and a Governor General’s residence. (See also Architectural Competitions.)

A wide variety of styles was submitted by architectural firms to the Department of Public Works. The designs were of two general styles: Neoclassical, which was identified at the time with American republicanism; and Gothic Revival, which had been used for the recently completed British Parliament in London, England. After discussions between Public Works commissioners and Governor General Sir Edmund Walker Head, the picturesque Gothic Revival style was chosen. It was thought to best represent the values of parliamentary democracy.

The Centre Block was awarded in 1859 to Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones. It was reworked in 1863 by Fuller and Charles Baillairgé. (See Baillairgé Family.) The East and West Blocks were awarded to Thomas Stent and Augustus Laver. The governor general's home was never built. Government departments began to move from Quebec City (the capital of the Province of Canada) to the new capital buildings in 1865. The original Centre Block and the two administrative blocks officially opened on 6 June 1866.

Parliament Buildings Design

The Parliament Buildings are excellent examples of highly developed Victorian Gothic revivalism. It was the most successful of the medieval revival styles of architecture in 19th-century Canada. (See also Architectural History: 1759–1867; Canadian Architecture: 1867–1914.) The buildings’ designs evolved from two streams of thought on Gothic architecture. One was the influence of the English architect Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. He saw the Gothic as an honest aesthetic because of its functionalism, creating buildings designed for their usability rather than their style. Pugin’s ideas were widely accepted at a time when picturesque sensibilities were strong.

A second influence was the notion of an authentic moral uprightness expressed through the Gothic’s high standards of craftsmanship. In the view of British theorist John Ruskin, Gothic architecture’s highly ornate decorativeness allowed a freedom of expression to anonymous craftsmen, who were increasingly inhibited by the Industrial Age.

The Parliament Buildings reflect both branches of Victorian Gothic revivalism. But they also reflect Canadian tastes through the eclectic choice of Gothic ornament and local materials. Each of the Parliament Buildings was designed to incorporate Gothic elements. These included pointed arches, lancet windows and tracery, spires with crockets and rubble-course stonework. In Pugin's tradition, a liberal and varied composition of projecting and receding masses produced the picturesque silhouettes of the buildings and the visual legibility of the plan. Ruskinian elements include the attention to minute details of ornamentation and a strong sense of polychromy, despite the replacement of the colourful slate tile of the mansard roofs with copper in later years.

When English author Anthony Trollope visited the Parliament Buildings he said: “I know no modern Gothic purer of its kind or less sullied with fictitious ornamentation.” The original Parliament Building complex had a strong impact both nationally and internationally. It set a course for federal building design over the following decades.

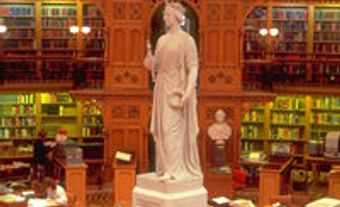

Library of Parliament

The present library building is the only part of the original Centre Block that survived the disastrous fire of 1916. It best exemplifies the High Victorian Gothic Revival style. (See also Library of Parliament.)

Destruction and Reconstruction

On the night of 3 February 1916, fire broke out in the Centre Block's House of Commons reading room. All that remained the following morning were the building's exterior walls and the Parliamentary Library. The library was spared thanks to the foresight of the first Parliamentary Librarian, Alpheus Todd. He helped draw up the building’s exact specifications and insisted that the library be separated from the rest of the building by a corridor. He also made sure the library’s main entrance had iron, fireproof doors. These key design features helped prevent the fire from spreading to the library. It was also thanks to library clerk Michael MacCormac that the doors were actually shut during the fire.

With Canada's energies focused on the First World War in Europe, the fire was rumoured to be an act of sabotage. It caused great alarm within the federal government, but according to a Royal Commission report, it proved to be an unfortunate accident due to either faulty wiring or a smoldering cigar.

Undeterred, the government rebuilt the Centre Block immediately. Architects John A. Pearson and Jean-Omer Marchand were selected to redesign the Centre Block in a style sympathetic to the original, but with modern materials and spatial planning. Reconstruction officially began on 24 July 1916. At first, the architects intended to rebuild on the footprint of the former Centre Block. But a decision to include more office space meant that an additional floor was needed. What was left of the original walls and foundation was demolished and rebuilt with load-bearing concrete walls and a steel frame.

Unlike the former Centre Block, the new building used a symmetrical bi-axial plan with major and minor corridors laid out according to principles held by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. (Marchand was one of the first Canadian architects to graduate from the school, in 1903.) The Beaux-Arts method of organizing space was achieved separately from a building's surface decoration or application of style. This approach is well illustrated in the Centre Block's main axis corridor linking the Parliamentary Library with the main public entrance. The two houses are aligned on secondary axes at each end of the building and are connected to the impressive two-storey Confederation Hall.

More than seven years were required to build most of the new Centre Block. It remained incomplete until the central Memorial Tower was officially opened on 11 November 1928.

The new Centre Block was intended to respect the original design, but it is fundamentally a building belonging to the 20th century and to Canada's wartime experience. It is stylistically sympathetic to the original's High Victorian Revival style in its recreation of the mansard-roofed end pavilions, the central tower and in its use of local stone and intricate ironwork. Inside, the two-storey Confederation Hall and the double-height chambers of each house are similar to the original.

Memorial Chamber, Peace Tower and Carillon

The new Centre Block was intended as a memorial to the Canadians who fought in the First World War. It therefore expressed through its design a stronger sense of nationhood. Throughout the building are reminders of its dedication to the valorous fallen soldiers. For example, there is a Memorial Chamber at the base of the tower containing a record of each soldier's name. A more discreet reminder is a small engraving on the west wall of the building noting the capture of Vimy Ridge, which had a deep impact on the country’s national image both at home and abroad.

A new sense of Canadian identity and iconography is evident throughout the building. It features symbolic carvings using materials and motifs from across the country. This sense of national consciousness differentiates the second Centre Block from the first.

The Peace Tower is a 92.2-meter-tall campanile functioning as both a clock and a bell tower. It is generally considered the most widely known symbol of Canada in the world, after the Canadian flag. The Peace Tower contains a carillon — a set of bells played via a keyboard. It includes 53 bells and weighs 54 tonnes. It is one of the largest carillons in North America. It is recognized the world over as a well-tuned example. The carillon was restored in 2023 as part of the Centre Block restoration project.

Centennial Flame

The centennial year of Confederation (1967) is remembered by a perpetual flame. The Centennial Flame is the centrepiece of the grounds. It remains alight at all times in a fountain near the front gate. The fountain was originally in the shape of a dodecagon — a 12-sided polygon. It had equal sections for each of the 10 provinces and two territories of Canada in 1967. In 2017, for Canada’s 150th anniversary, the fountain was rebuilt as a tridecagon (13-sided polygon) to include Nunavut, which became a territory in 1999. Each section includes a bronze shield featuring the province or territory’s coat of arms, the year it joined Confederation and its floral emblem.

Cat Colony

For about 30 years, beginning in the mid-1920s, cats were used to control a rodent problem in the Parliament buildings and around Parliament Hill. When chemicals began to be used for rodent control in the mid-1950s, the resident cat population was moved outdoors. A feral cat colony eventually formed.

Groundskeepers and custodians took care of the cats for many years. Volunteers took up the job in the mid-1980s. Small structures resembling barns were built in which the cats could live. By the 1990s, the colony had become a small tourist attraction. Its numbers eventually dwindled thanks to neutering and adoption programs. The last cat was adopted in 2013 and the cat houses were destroyed.

Preserving a Public Space

The Parliament Buildings have come to be an enduring and important national symbol for Canada. As such, the federal government has in place a heritage conservation program to preserve both the architectural and heritage values of the complex and grounds.

Awareness of the buildings' importance was not always the case. In the late 1950s, in need of more office space, the government decided to demolish the West Block and replace it with a large modern office building. Public outcry forced the government to reconsider the plan and to renovate the building instead. Over recent decades, each building has undergone a sensitive conservation process.

Recent Renovations

Renovating, rehabilitating and restoring the Parliament Buildings (in whole or in part) has been an ongoing effort since the 1970s.

Beginning in 2002, Public Services and Procurement Canada undertook the most significant and thorough renovation and restoration project since the Centre Block was rebuilt after the 1916 fire. The National Capital Commission, the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons were also involved in the project. WSP provides engineering and project management services. HOK serves as architect of record, leading architectural design and conservation efforts, as well as landscape architecture. Architecture49, DFS and ERA Architects also assist with the project.

The Sir John A. Macdonald Building and the Wellington Building — both located on the south side of Wellington, across from the Parliament buildings — were renovated first. They re-opened in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The West Block was rehabilitated between 2010 and 2018 in preparation for the extensive renovation of the Centre Block. This project involved creating a new Visitor’s Welcome Centre as well as the new temporary facility for the House of Commons Chamber. The Senate was relocated to the Government Conference Centre.

This effort aims to restore the building after decades of deterioration, as well as to improve its resistance to both fires and earthquakes and lower the building’s overall carbon footprint. It will also seek to upgrade, improve, and/or replace heating, ventilation, electrical, plumbing and communications systems. Since 2002, preservation efforts have included replacing the roof, removing asbestos, upgrading the buildings’ heating and cooling systems and restoring its decorative features.

The Centre Block project began in 2018. The building was officially vacated and parliament was moved to its temporary location in the courtyard of the West Block. 40,000 truckloads of earth and rock were removed from in front of Centre Block to make room for a new three-story underground visitors complex. It will include new exhibition space and educational facilities, as well as new security facilities. The Centre Block is expected to be completed in 2031, at a cost of between $4.5 and $5 billion.

For the most part, the Parliament Buildings are to be restored to their original state. The exception is the glass canopy over the West Block’s former courtyard (which currently serves as a temporary chamber for the House of Commons) and the new underground visitor’s centre in front of the Centre Block. These two additions are new and not in keeping with the original look of the buildings and Parliamentary precinct, but they are minimally invasive. Despite this, not everyone was happy with the West Block’s new glass roof. Some MPs complained it was out of sync with the rest of the building, while others noted the cost.

The decision to keep the look and feel of the Parliament buildings and the precinct in general is a result of the buildings’ globally emblematic status as symbols of Canada. In addition, the Parliament buildings — a unique collection of landmark Gothic Revival architecture — have been protected as a National Historic Site since 1976.

Historic Land Deal with First Nations

In October 2016, the federal government agreed to give 115,500 acres (475.5 km2) of Crown Land to the Algonquins of Ontario. The area stretches from Ottawa to North Bay and includes much of the Ottawa Valley and Parliament Hill. The agreement also includes a cash payment of around $300 million. It is the first modern-day treaty in Ontario and was the result of 24 years of negotiations.

However, in December 2016, the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation across the Ottawa River in Quebec filed an Aboriginal title claim for the sites of Parliament Hill, the Supreme Court of Canada and Lebreton Flats. The Algonquin Anishinabe claim a historical right to the land and oppose the government’s deal with the Algonquins of Ontario. Jean-Guy Whiteduck, chief of the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation, said, “We're not against any sound, environmentally-friendly, development. And we're not about to displace anyone, that's not our intention. We're just saying that the land belongs to us, there has to be real consultation with us.”

As of January 2024, the treaty was in the final stage of negotiations.

(See also National Capital Commission; National Historic Sites in Canada; Parliament; House of Commons; Senate.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom