The Pacific Scandal (1872–73) was the first major post-Confederation political scandal in Canada. In April 1873, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and senior members of his Conservative cabinet were accused of accepting election funds from shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan in exchange for the contract to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. The affair forced Macdonald to resign as prime minister in November 1873. But it did not destroy him politically. Five years later, Macdonald led his Conservatives back to power and served as prime minister for another 18 years.

Background

At the time of the Pacific Scandal, the financial activities of political parties were mostly unregulated. (See Political Party Financing in Canada.) From Confederation until about 1897, the Liberal and Conservative parties both tended to rely on corporate donations. This led to periodic scandals. (See also Political Corruption.)

In 1871, British Columbia was lured into the Dominion of Canada under the promise that a transcontinental railway would be built within 10 years. (See Railway History.) The proposed line was 1,600 km longer than the first American transcontinental. It represented an enormous expenditure for a nation of only three and a half million people. Two syndicates vied for the contract, including the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Campaign Donation

The Pacific Scandal originated when Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and his Conservative colleagues Sir George-Étienne Cartier and Hector-Louis Langevin went looking for campaign funds for the 1872 general election. (See Political Campaign.) The target of their solicitations was Sir Hugh Allan, a Montreal shipping magnate and railway builder. The Conservatives needed money to compete in the election; particularly in Ontario and Quebec, where it appeared they might lose several seats.

Financed partly by American backers, Allan donated more than $350,000 to the Conservative campaign. Despite the financial boost, the Conservatives did poorly in the vote. While Macdonald held on to power, the majority government he won in 1867 was greatly reduced.

After the election, a railway syndicate organized by Allan was rewarded with the profitable contract to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Allan was given the contract on the assumption that he would remove American control on the syndicate’s board of directors. But Allan, unknown to Macdonald, had used American money to supply the campaign funds to the Conservatives.

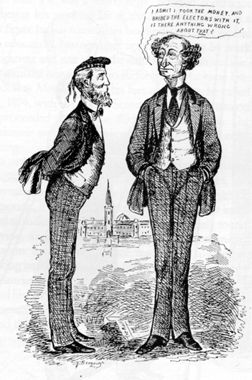

This Pacific Scandal cartoon by John Wilson Bengough shows Sir John A. Macdonald explaining to Alexander Mackenzie, the leader of the opposition: “I admit I took the money and bribed the electors with it. Is there anything wrong about that?”

Unearthing the Scandal

Sir Hugh Allan was a prolific letter-writer. He kept records of his correspondence with Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. While Allan and his lawyer, John Abbott, were in England securing funds for the Canadian Pacific Railway, Abbott’s private secretary, George Norris, and an accomplice stole incriminating letters that Allan had left with Abbott for safekeeping.

The letters showed that an agreement existed between Allan and the Conservatives; notably Macdonald, Cartier and minister of public works Hector-Louis Langevin. The deal assured Allan the railway contract in return for campaign funds. Norris sold the documents for $5,000 to Liberal opposition members. They broke news of the scandal in the House of Commons on 2 April 1873.

Conservatives Resign

In response to Liberal accusations, Macdonald claimed that his “hands were clean” because he had not profited personally from his association with Allan. However, by his own admission, Macdonald — who was a heavy drinker — could not remember periods of time during the 1872 election campaign and the negotiations with Allan. Days after the matter entered the House of Commons, the Macdonald government convened a parliamentary committee to investigate allegations of conflict of interest and corruption.

When the committee first met in July, a litany of damaging letters and telegrams appeared in Liberal newspapers. One of the most sensational pieces of evidence against the prime minister was a telegram from Macdonald to John Abbott: “I must have another ten thousand; will be the last time of calling; do not fail me; answer today.” In another, Allan had written to his American financiers to report that he would be made president of the CPR “on certain monetary conditions.” According to published opinion, Macdonald had “obtained money from a suspicious source [and] applied it to illegitimate purposes.”

By August, when it appeared that the committee’s report would implicate Macdonald in the scandal directly, he asked Governor General Lord Dufferin to prorogue (suspend) Parliament. Lord Dufferin granted a 10-week prorogation; but he warned Macdonald that “your personal connection with what has passed cannot but fatally affect your position as minister.” Macdonald convened a royal commission to investigate while Parliament was suspended.

When the House of Commons reconvened on 23 October, several Conservative members of Parliament (MPs) left the party. Many of these MPs, including Donald Smith (who would later be named president of the CPR, as well as Lord Strathcona), joined opposition leader Alexander Mackenzie in his call for a vote of confidence. The Conservative’s weakening majority was further threatened by the likelihood that members from the new province of Prince Edward Island would also vote against the government. Macdonald realized that his government would lose the confidence of the House. He asked the governor general to dissolve Parliament on 5 November.

Did You Know?

Donald Smith later became director of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He was famously photographed driving the ceremonial Last Spike of the completed transcontinental railway on 7 November 1885. He was named Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal in 1897.

Donald Smith driving the Last Spike to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway on 7 November 1885.

Allan’s company never did get started. A new contract agreement to build the Canadian Pacific Railway had to wait until 1880. The Liberals were invited by Lord Dufferin to form government. Mackenzie became Prime Minister. An election was called for January 1874; the Liberal party formed a large majority, winning 138 of 206 seats in the House of Commons.

Macdonald’s Comeback

The scandal was the final political struggle for Sir George-Étienne Cartier. He had lost his Montreal East seat in the 1872 election but was acclaimed to the Manitoba riding of Provencher a month later. Cartier was at the centre of the scandal because he had written the letter offering the railway contract to Allan. He died one month after the scandal broke, on 20 May in London, England, where he was receiving treatment for Bright’s disease.

Macdonald offered to resign as Conservative leader the day after he stepped down as prime minister. However, the Conservative caucus refused his resignation. Macdonald would rise to become prime minister again when his party won the 1878 election. He remained prime minister until his death in 1891. He was succeeded, ironically, by John Abbott, Sir Hugh Allan’s lawyer at the time of the scandal.

Langevin’s Legacy

Sir Hector-Louis Langevin left politics in 1873 because of his role in the Pacific Scandal. He attempted a return to federal politics in the 1878 election; but he lost in the riding of Rimouski. A month later, he was acclaimed to the vacant riding of Trois Rivieres and became Minister of Public Works; the Cabinet post he held when the government resigned in 1873. But his fortunes changed after the death of Macdonald in 1891. That year, he was implicated with MP Thomas McGreevy in the so-called McGreevy-Langevin scandal. This affair was even uglier. It involved kickbacks from federal contracts to McGreevy. Langevin stepped down as public works minister and was exiled to the backbenches until he left politics in 1896. McGreevy was sentenced to a year in jail.

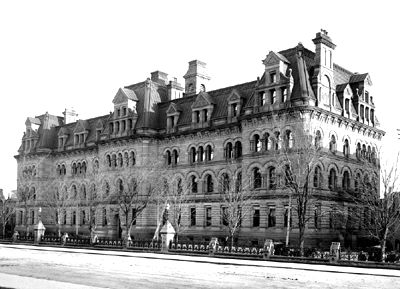

From 1889 until 2017, the building that houses the Prime Minister’s Office in Ottawa was named Langevin Block, after Sir Hector-Louis Langevin. However, the large, limestone building across from Parliament Hill was renamed the Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council when it came to light that Langevin had played a role in the creation of the residential schools system.

See also Political Patronage in Canada; Political Corruption; Conflict of Interest.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom