The One Big Union (OBU) was a radical labour union formed in Western Canada in 1919. It aimed to empower workers through mass organization along industrial lines. The OBU met fierce opposition from other parts of the labour movement, the federal government, employers and the press. Nevertheless, it helped transform the role of unions in Canada.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

The logo appears in a One Big Union bulletin titled “The Workers’ Party and the One Big Union,” published 18 May 1922.

Background

As with many countries in the industrialized world, labour unions began in Canada in the 1800s. The first to form them were skilled labourers. Workers organized within specific trades, such as typesetting or bricklaying. Their unions tended to focus on issues specific to those trades, including certification and working conditions (see Craft Unionism).

In the early 1900s, syndicalism, a more radical form of labour organizing, became more popular worldwide. It argued that, as capitalist enterprise and state governments grew in power, the only way for workers to ensure their rights was to organize on a mass scale. A notable syndicalist union was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). It was based in the United States and had chapters in the Canadian West. In 1911, the IWW outlined its philosophy in a pamphlet titled One Big Union. That phrase also became the IWW’s slogan.

Syndicalist ideas struggled to catch on in Eastern Canada. The eastern labour unions, allied with the American Federation of Labor, enforced the status quo. They sometimes expelled members who sought to organize across professional lines. Syndicalism proved more popular in Western Canada. The West had a larger proportion of unskilled labourers, a large immigrant population and closer ties to radical American union organizers. However, labour unions nationwide kept their traditional structures until 1919.

Formation

Divisions between labour movements on either side of the country gradually grew. During the First World War, they came to a head. The Eastern-dominated Trades and Labour Congress of Canada (TLC) called for the United States to join the war and supported conscription. These acts outraged Western labour leaders, who condemned Canada’s involvement in the war. In 1918, as part of the War Measures Act, the Conservative government of Sir Robert Borden outlawed many radical political and labour groups. The ban included the IWW and groups representing German, Ukrainian and Polish speakers, many of whom participated in Western labour unions. Over the next several months, many labour leaders were arrested for participating in protests and outlawed unions.

On 13 March 1919, nearly 240 delegates of labour unions from Victoria to Winnipeg met in Calgary. They voted to leave their existing unions and the TLC and form a new union. This new union would organize along industrial lines and across professions. That June, the delegates met again to officially create the National Industrial Union of the Dominion of Canada, which became known as the One Big Union (OBU).

Excerpt from the One Big Union charter

The One Big Union . . . seeks to organize the wage worker not according to craft but according to industry; according to class and class needs; and calls upon all workers irrespective of nationality, sex, or craft to organize into a workers’ organization, so that they may be enabled to more successfully carry on the everyday fight over wages, hours of work, etc. and prepare themselves for the day when production for profit shall be replaced by production for use.

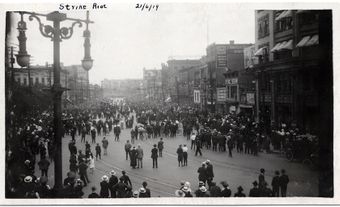

Winnipeg General Strike

Between the vote to secede and the creation of the One Big Union, the Winnipeg General Strike began. It was the largest strike in Canadian history. Though the OBU itself was not officially involved, many of those who helped found it also helped organize the strike — and were arrested for participating in it. The tactics of a mass general strike fit with the OBU’s overall philosophy.

Decline and Legacy

The One Big Union expanded its membership throughout 1919. By early 1920, it peaked at more than 40,000 members. However, it faced fierce opposition in the backlash against radical labour following the Winnipeg General Strike. Its opponents included the more conservative Trades and Labour Congress. In July 1919, the federal government passed Section 98. This addition to the Criminal Code extended the wartime ban of labour and political groups to peacetime. Newspapers accused the OBU of trying to lead a Bolshevik revolution in Canada. Some employers refused to negotiate with OBU members. This led to workers abandoning the OBU for other unions.

Facing these pressures and internal disagreements around organizing and tactics, OBU membership dwindled to as few as 5,000 members in 1922–23. The loss of membership gradually reduced the OBU’s radical idealism. In 1927, it joined with other labour groups to form the All-Canadian Congress of Labour, and later the Canadian Federation of Labour. The OBU began to focus more on the conditions of its members and less on mass organization. Membership gradually grew back to as many as 24,000 workers in the 1940s, almost entirely within the city of Winnipeg. The OBU was formally dissolved and absorbed into the Canadian Labour Congress in 1956.

Though the OBU’s period of influence was brief, many of its organizers went on to play prominent roles. They took part in labour, socialist and communist movements in Canada through the 1920s and ’30s (see also Communist Party of Canada). The OBU’s radical ideas also influenced a more progressive and politically active style of labour unionism in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom