The October Crisis refers to a chain of events that took place in Quebec in the fall of 1970. The crisis was the culmination of a long series of terrorist attacks perpetrated by the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), a militant Quebec independence movement, between 1963 and 1970. On 5 October 1970, the FLQ kidnapped British trade commissioner James Cross in Montreal. Within the next two weeks, FLQ members also kidnapped and killed Quebec Minister of Immigration and Minister of Labour Pierre Laporte. Quebec premier Robert Bourassa and Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau called for federal help to deal with the crisis. In response, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau deployed the Armed Forces and invoked the War Measures Act — the only time it has been applied during peacetime in Canadian history.

Background

The FLQ was founded in 1963, during a period of profound political, social and cultural change in Quebec. (See also Quiet Revolution; Francophone Nationalism in Quebec.) Members of the FLQ — or felquistes — were influenced by anti-colonial and communist movements in other parts of the world, particularly Algeria and Cuba. Felquistes shared a conviction that Quebec must liberate itself from anglophone domination and capitalism through armed struggle. Their objective was to destroy the influence of English colonialism by attacking its symbols. They hoped that Quebecers would follow their example and rise up to overthrow their colonial oppressors.

Between 1963 and 1970, felquistes were responsible for more than 200 bombings and dozens of robberies that left six people dead. Their targets included numerous mailboxes in Westmount, a wealthy, anglophone area of Montreal; several Canadian Armed Forces armouries and facilities; the head office of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) in Montreal; a federal government bookstore; McGill University; the residence of Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau; the provincial Department of Labour; and the Eaton’s department store in downtown Montreal. In February 1969, an FLQ bombing at the Montreal Stock Exchange injured 27 people.

One of the most spectacular actions of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) involved the explosion of a bomb at the Montréal Stock Exchange in 1969. The photos show the damage caused by the explosion outdoors and inside the building. La Presse, February 4th, 1969, p. 7.

By 1970, more than 20 FLQ members were in prison for these acts of violence. Four felquistes were sentenced to between 6–12 years imprisonment after pleading guilty to manslaughter in the death of a night watchman at an Armed Forces recruitment centre in April 1963. Pierre Vallières, a former journalist who joined the FLQ in 1965, wrote his controversial autobiography, Nègres blancs d'Amérique (1968), while jailed in New York for FLQ activities. Pierre-Paul Geoffroy, who was responsible for 31 bombings including the explosion at the Montreal Stock Exchange, received 124 life sentences plus 25 years; it was, at the time, the longest prison sentence ever levied in the British Commonwealth.

Beginning of the Crisis

In the fall of 1969, the remaining FLQ movement split into two distinct Montreal-based cells. The South Shore gang, which became the Chénier cell, was led by Paul Rose; other members were his brother Jacques Rose, Bernard Lortie and Francis Simard. The Liberation cell was led by Jacques Lanctôt; other members were his sister Louise Lanctôt and her husband, Jacques Cossette-Trudel, as well as Marc Carbonneau, Nigel Barry Hamer and Yves Langlois.

Shortly after 8 a.m. on 5 October 1970, three armed members of the Liberation cell, one disguised as a deliveryman, kidnapped British trade Commissioner James Cross from his home in Montreal. In exchange for the release of Cross, the cell issued seven demands; they included the release of 23 FLQ “political prisoners,” the broadcast and publication of the FLQ manifesto, $500,000, and safe passage to Cuba or Algeria. The Quebec government was given 24 hours to comply; it rejected the ultimatum but indicated it was willing to negotiate.

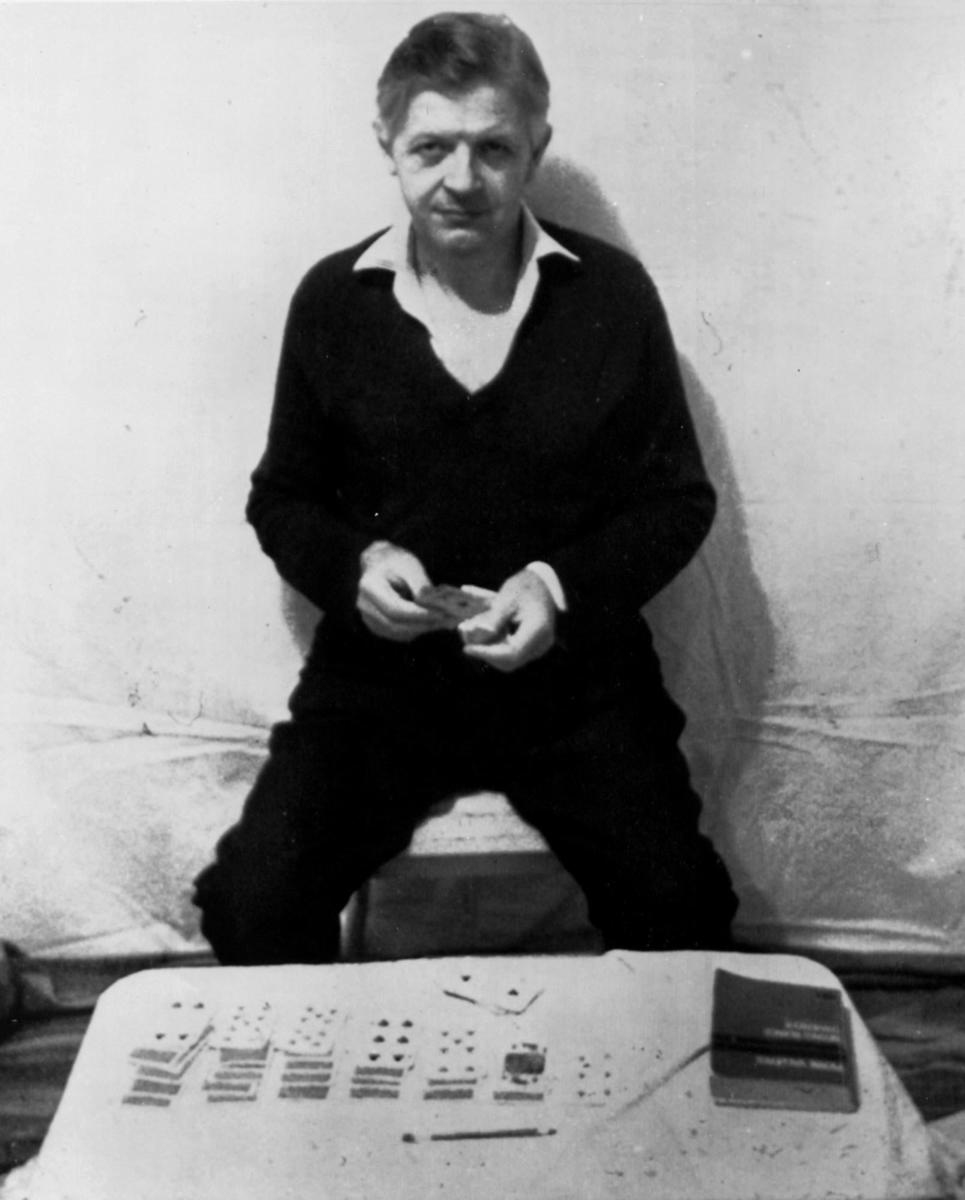

British Trade Commissioner James Cross plays solitaire almost one month after his kidnapping in this photo released by his FLQ kidnappers in early November 1970.

In the days that followed, police arrested 30 people following a series of dawn raids. Several French newspapers published the FLQ manifesto — a diatribe against established authority that was also read on Radio-Canada. Parti Québécois leader René Lévesque published a newspaper article imploring the FLQ not to inflict violence on Cross or anyone else. The Liberation cell provided proof that Cross was still alive and extended its deadline for its demands to be met to 10 October at 6 p.m.

On 10 October, shortly before the 6 p.m. deadline, Quebec justice minister Jérome Choquette announced that if Cross were released, the Liberation cell would be granted safe passage out of Canada; but none of their other demands would be met. Shortly after the deadline passed, two masked members of the Chénier cell kidnapped Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte while he was playing with his nephew on his front lawn in Saint-Lambert. (They had found his address in the phone book.)

Crisis Intensifies

Following the kidnapping of Laporte, elected officials in Quebec flooded the police with requests for protection. On 11 October, the Chénier cell issued a communiqué; they threatened to kill Laporte unless all seven FLQ demands were met by 10 p.m. It also released two letters written by Laporte — one to his wife and one to Premier Robert Bourassa. Shortly before 10 p.m., Bourassa announced on the radio that he would not meet the FLQ’s demands but that he was open to further negotiations. The Chénier cell responded by postponing Laporte’s execution.

On 12 October, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau asked the Canadian Armed Forces to deploy soldiers in Ottawa to protect high-profile people and locations. The next day, CBC reporter Tim Ralphe questioned Trudeau at the front entrance of the Parliament Buildings. Ralphe expressed concern about the heavy military presence in the city. Trudeau replied, “Yes, well there are a lot of bleeding hearts around who just don’t like to see people with helmets and guns. All I can say is, go on and bleed, but it is more important to keep law and order in the society than to be worried about weak-kneed people.” Ralphe asked Trudeau exactly how far he was willing to go. Trudeau responded, “Well, just watch me.” Meanwhile, Robert Demers, a senior official in the Quebec Liberal Party, began negotiating with FLQ lawyer Robert Lemieux.

On 15 October, the Quebec government formally requested assistance from the Armed Forces to supplement the local police. Within an hour, 1,000 soldiers were deployed at key locations in Montreal. Bourassa and Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau requested further federal assistance. That afternoon, around 3,000 students attended a rally in support of the FLQ; they called on the governments to meet the terrorists’ demands. Later that evening, the Quebec government announced it would release five FLQ prisoners on parole and guarantee the two cells safe passage out of Canada in exchange for the return of the hostages.

War Measures Act and Murder of Laporte

On 16 October, at the request of Premier Bourassa, the municipal government of Montreal and the Montreal police force, the federal government invoked the War Measures Act to confront the state of “apprehended insurrection” in Quebec. Under the emergency regulations, the FLQ was outlawed and membership became a criminal act; normal civil liberties were suspended, and arrests and detentions were authorized without charge.

Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield, former prime minister John Diefenbaker and NDP leader Tommy Douglas all voiced dissenting opinions in the House of Commons. Douglas, a longtime champion of civil liberties (see Saskatchewan Bill of Rights), likened the move to using “a sledgehammer to crack a peanut.” René Lévesque and Le Devoir publisher Claude Ryan also condemned the decision. However, public opinion polls indicated a clear majority supported invoking the Act.

Within 48 hours of Trudeau’s invocation of the War Measures Act, more than 250 people were arrested. On 17 October, at 10:50 p.m., Laporte’s body was found in the trunk of an abandoned car near the Saint-Hubert airport. An autopsy later revealed that he had been strangled.

The Manhunt

On 18 October, warrants were issued for the arrest of Marc Carbonneau and Paul Rose. They were wanted in connection with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte. Police issued additional warrants for the other members of the Chénier cell — Jacques Rose, Bernard Lortie and Francis Simard — on 23 October. By 20 October, police had conducted 1,628 raids under the War Measures Act.

On 26 October, an appeal from Barbara Cross, James Cross’s wife, to the FLQ was broadcast on radio station CKLM. “To those holding my husband,” she said, “ I wish to express my confidence that, as he is a victim of circumstances, he will be well treated. I entreat them to free him without further delay.” Meanwhile, the Quebec justice minister announced that members of the Quebec Civil Liberties Union would be allowed to visit people who had been detained under the War Measures Act.

On 2 November, the federal government and the Quebec government jointly offered a $150,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the kidnappers. On 6 November, police raided an apartment in Côte des Neiges and arrested Bernard Lortie. However, the other members of the Chénier cell hid behind a false wall in a closet and slipped away the next day.

Cross’s Release

By 13 November, charges had been laid against 46 people detained under the War Measures Act. On 21 November, a letter from Cross dated 15 November was received by the authorities, confirming that he was still alive.

Jacques Cossette-Trudel and his wife Louise Lanctôt were arrested by Montreal police on 2 December. By the next day, police had negotiated the release of James Cross in exchange for safe passage of all members of the Liberation cell, including Cossette-Trudel and Lanctôt and their infant daughter, to Cuba. After being held in a room in a Montreal North apartment for 59 days, Cross had lost 22 pounds but was otherwise in good health. He had not been harmed and described his captors as courteous.

Crisis Ends

Paul and Jacques Rose and Francis Simard were arrested on a farm southeast of Montreal on 28 December. They and Bernard Lortie were charged with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte on 5 January 1971. Paul Rose was sentenced to life imprisonment for kidnapping and murder; Francis Simard was sentenced to life for murder; Bernard Lortie was sentenced to 20 years for kidnapping; and Jacques Rose was acquitted of kidnapping and murder but was sentenced to eight years for being an accessory after the fact in the kidnapping of Laporte.

All the members of the Liberation cell, who were granted safe passage out of Canada in exchange for the release of James Cross, eventually returned to Canada. Jacques Cossette-Trudel and his wife Louise Lanctôt were sentenced to two years in prison on 7 August 1979 and were released on parole in April 1980. Jacques Lanctôt returned in January 1979. In addition to kidnapping charges in the case of Cross, he was also charged with conspiracy to kidnap Israeli trade commissioner Moshe Golem. Nigel Barry Hamer was sentenced to 12 months in jail on 21 May 1981. Marc Carbonneau was sentenced to 20 months in jail and three years probation on 23 March 1982. Yves Langlois, the final member of the Liberation cell to return from exile, was sentenced to two years in prison; he was paroled on 27 May 1983.

War Measures Act and Civil Rights Abuses

The federal response to the kidnappings was intensely controversial. Opinion polls showed that a majority of Canadians supported the federal cabinet's action. But invoking the War Measures Act was criticized as excessive by Quebec nationalists and by civil libertarians throughout the country. A total of 497 individuals were arrested under both the War Measures Act and the Public Order Act; it replaced the War Measures Act on 1 December and was in effect until 30 April 1971. Four hundred and thirty-five people were released and 62 were charged (32 of these were held without bail). In spring 1971, the Quebec government announced that it would pay up to $30,000 in compensation to roughly 100 people who were unjustly detained.

After the crisis, the federal cabinet gave ambiguous instructions to the RCMP Security Service; dubious acts such as break-ins, thefts and electronic surveillance were permitted, all without warrants. These tactics were later condemned as illegal by the federal McDonald Commission and the Keable Inquiry in Quebec, both of which issued their reports in 1981. The McDonald Commission called for the creation of a new civilian security agency, separate from the RCMP; this led to the establishment of the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS) in 1984.

In 1988, the War Measures Act was repealed and replaced by the Emergencies Act. It created more limited and specific powers for the government to deal with security emergencies. Under the Emergencies Act, Cabinet orders and regulations must be reviewed by Parliament and are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

In Popular Culture

Pierre Vallières published The Assassination of Pierre Laporte in 1977. It focuses on the actions taken by police and government officials that, in Vallières’s estimation, contributed to the death of Laporte. Francis Simard’s autobiography, Talking It Out: The October Crisis from Inside, was published in 1987.

The National Film Board released two acclaimed documentaries about the crisis in 1973 — Action: The October Crisis of 1970 and Reaction: A Portrait of a Society in Crisis — both directed by Robin Spry. Michel Brault became the only Canadian ever to win the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival with Les Ordres (1974). Based on the experiences of 50 people who were detained during the crisis, it is widely regarded as one of the best Canadian films ever made.

Pierre Falardeau, a staunch Quebec nationalist, created controversy in 1994 with the feature film Octobre. Adapted from Francis Simard’s autobiography, the film paints a sympathetic portrait of the Chénier cell members and their kidnapping and murder of Laporte. In 2000, CBC TV broadcast Black October (2000), a two-hour documentary about the crisis featuring interviews with Pierre Trudeau and James Cross. In 2006, it aired October 1970, an eight-part mini-series starring R.H. Thomson as Cross and Denis Bernard as Laporte. In 2010, for the 40th anniversary of the crisis, Radio-Canada broadcast a radio documentary about the crisis and its ramifications; it featured an interview with Pierre Laporte’s nephew, Claude Laporte, who witnessed his uncle’s kidnapping.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom