Early Life

As the son and nephew of printers, Henri Julien studied at Abbot Joseph Chabert’s art school in Ottawa. Around 1868, he began his career as an engraver and lithographer with Georges-Édouard Desbarats, the Queen’s Printer (see Print Industry), where he also learned to draw and paint. At that time, photoengraving had not yet been invented, and instead of published photos to accompany their articles, newspapers often contained images drawn by illustrators. Julien illustrated articles for three of Desbarats’s publications: the Canadian Illustrated News, L’Opinion publique, and Hearthstone. At the Canadian Illustrated News, he was influenced by illustrators Edward Jump, Charles Kendrick and Bohuslar Kroupa. He also drew political cartoons and collaborated with nearly every satirical newspaper at the time, including Le Canard, Le Farceur, Le Franc Parleur, Le Grelot, Le Violon and Le Vrai Canard. Julien’s drawings quickly became known by a wide audience. He often signed his political cartoons under the pseudonyms Crincrinand Octavo.

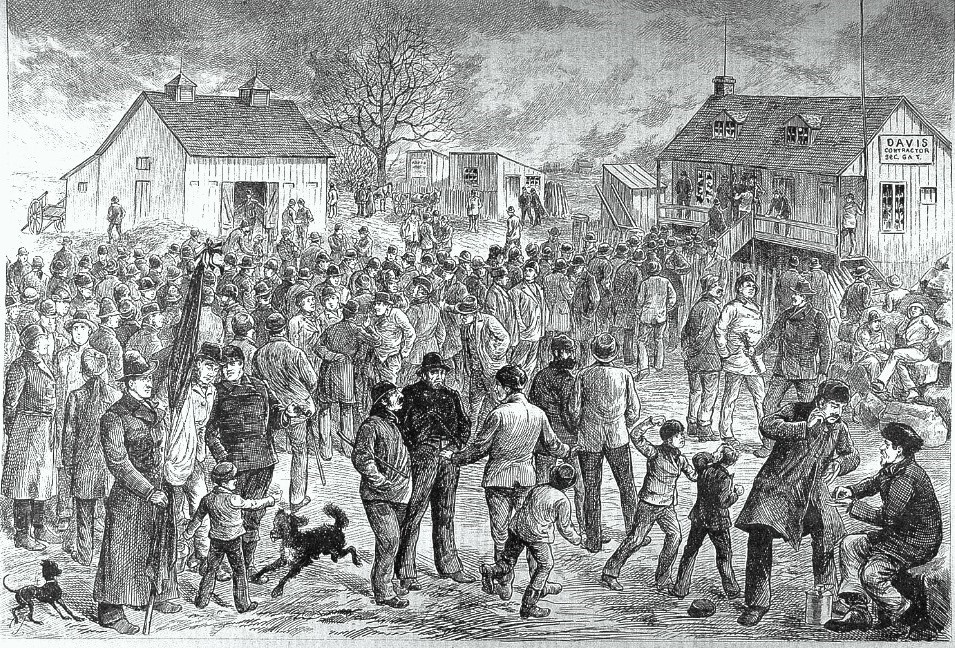

In 1874, Julien accompanied the North West Mounted Police’s expeditionary force, which was commanded by George-Arthur French to end the smuggling of alcohol in the Prairies. During that trip, he also made illustrations of life in the West for the Canadian Illustrated News. His visual memory was so impressive that he was able to perfectly reproduce scenes he had seen several days earlier — a huge advantage in such a challenging work environment.

Artistic Director for the Montreal Daily Star

In 1888, Julien became the artistic director for the Montreal Daily Star, where he proved his talent as a political cartoonist. He quickly became the most well-known newspaper illustrator in Canada. He drew outstanding caricatures of Sir Wilfrid Laurier and his Cabinet, particularly between 1897 and 1900, when he sketched them from the press gallery in a series of famous political cartoons entitled the By-Town Coons. The series presented the group in the form of a minstrel show—a burlesque performance that traditionally involved singers and comedians in blackface. Julien’s quick wit and strong sense of humour gave birth to some of the best political commentaries of the day.

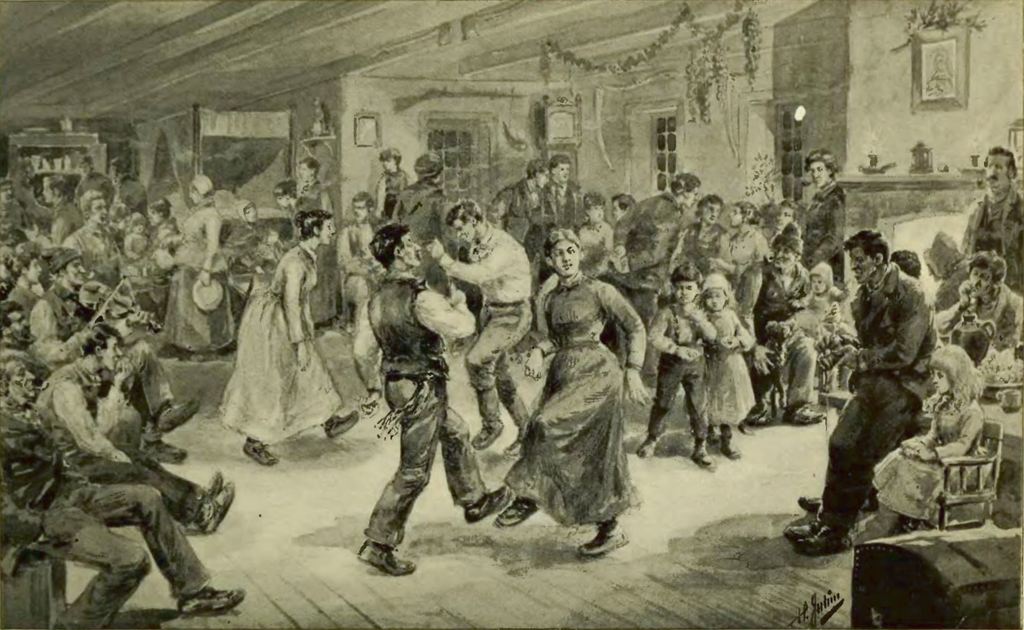

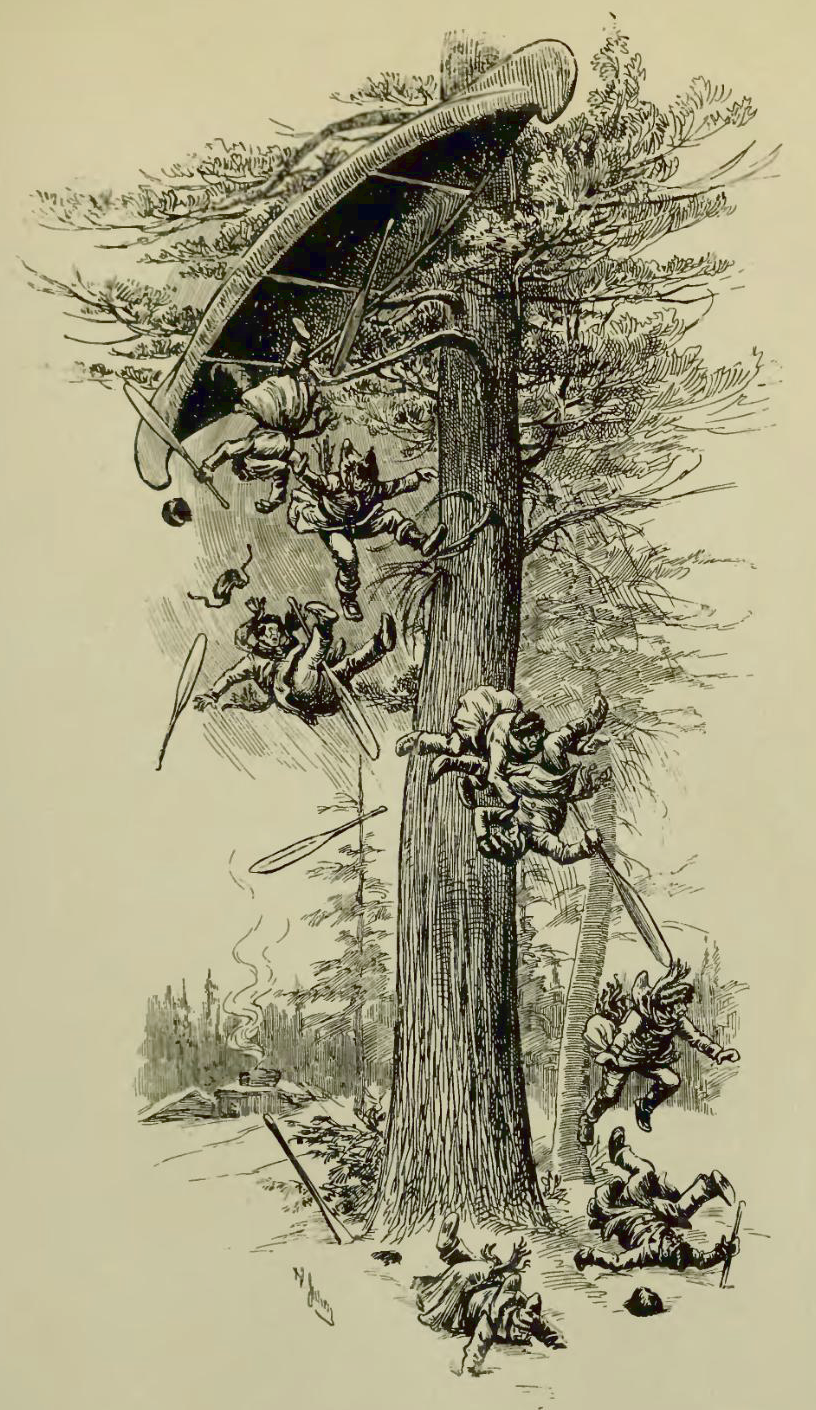

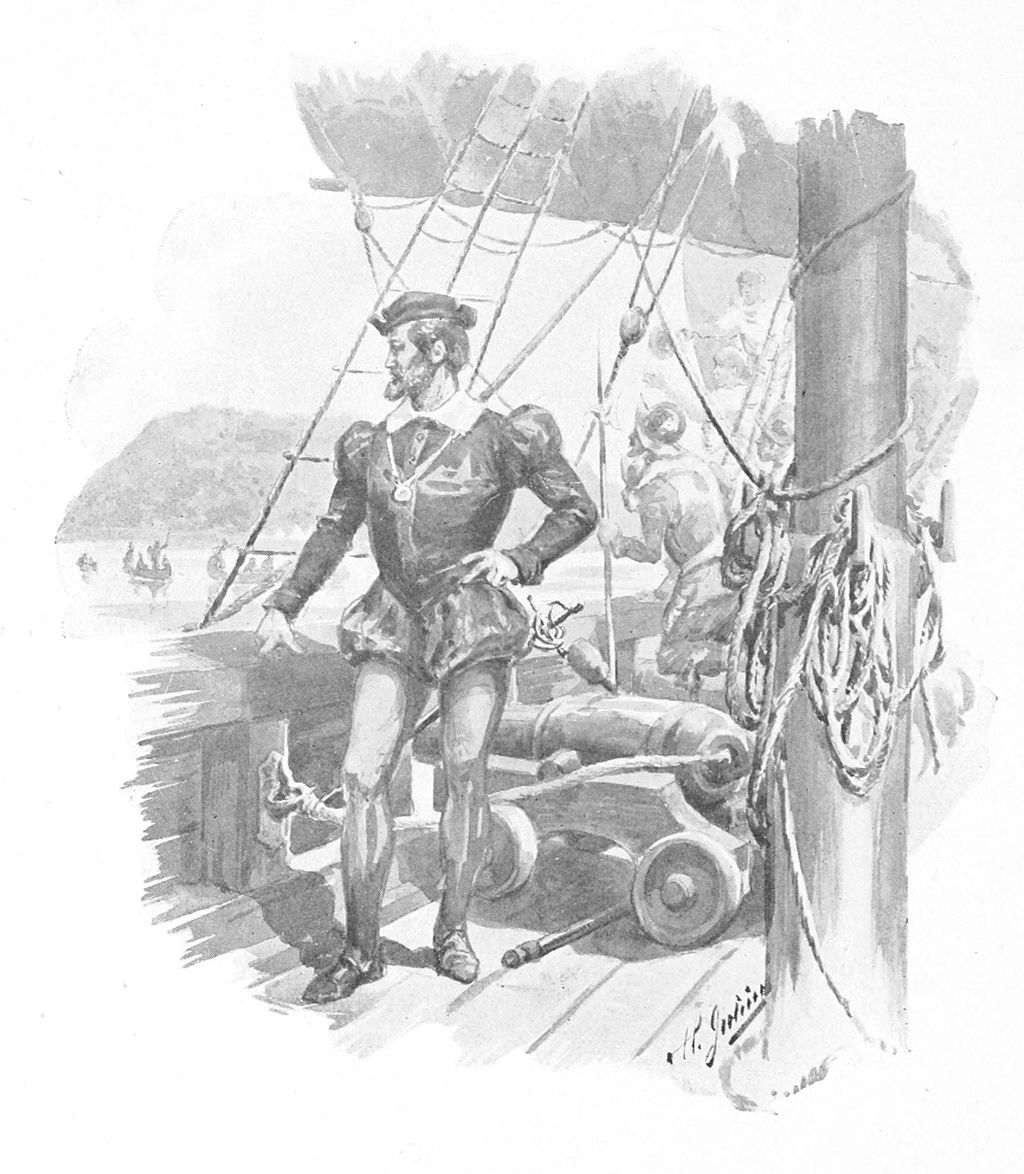

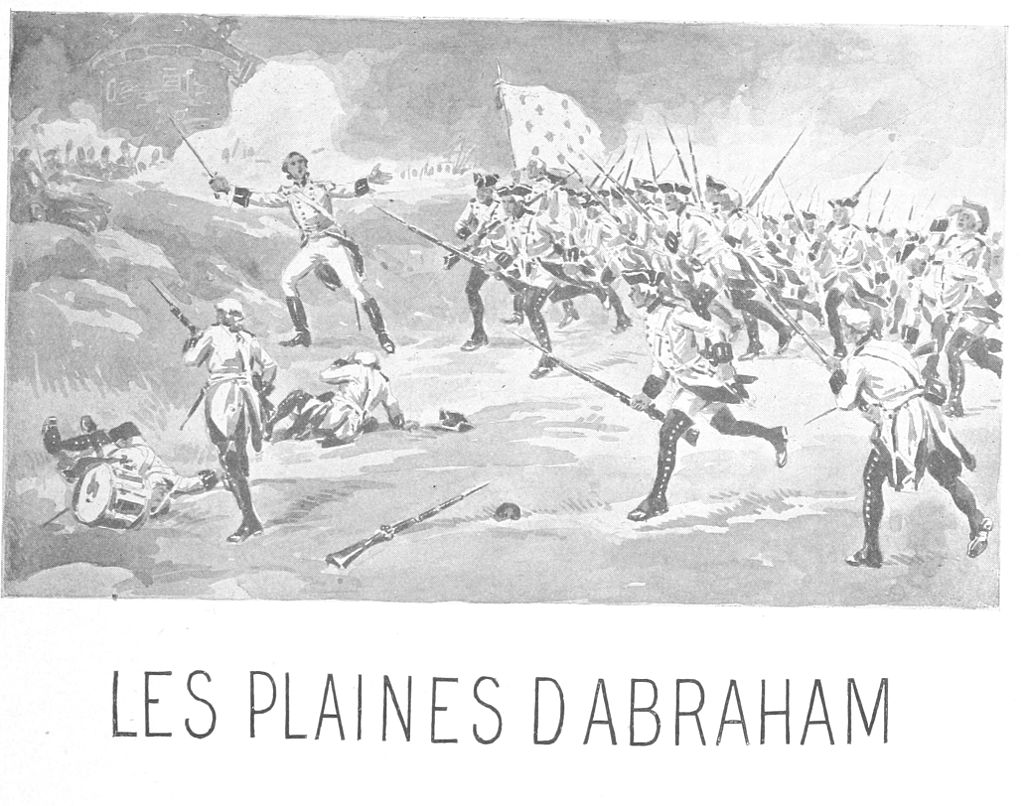

During this time, Julien also illustrated the following works: Les anciens Canadiens by Philippe-Aubert de Gaspé, La légende d’un peuple by Louis Fréchette, La chasse-galerie by Honoré Beaugrand, Les contes vrais by Pamphile Lemay, and Mélanges poétiques by Félix-Gabriel Marchand. He also created watercolours and oil paintings and regularly exhibited his work through the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

He died suddenly at age 56 as a result of a heart attack.

Style and Legacy

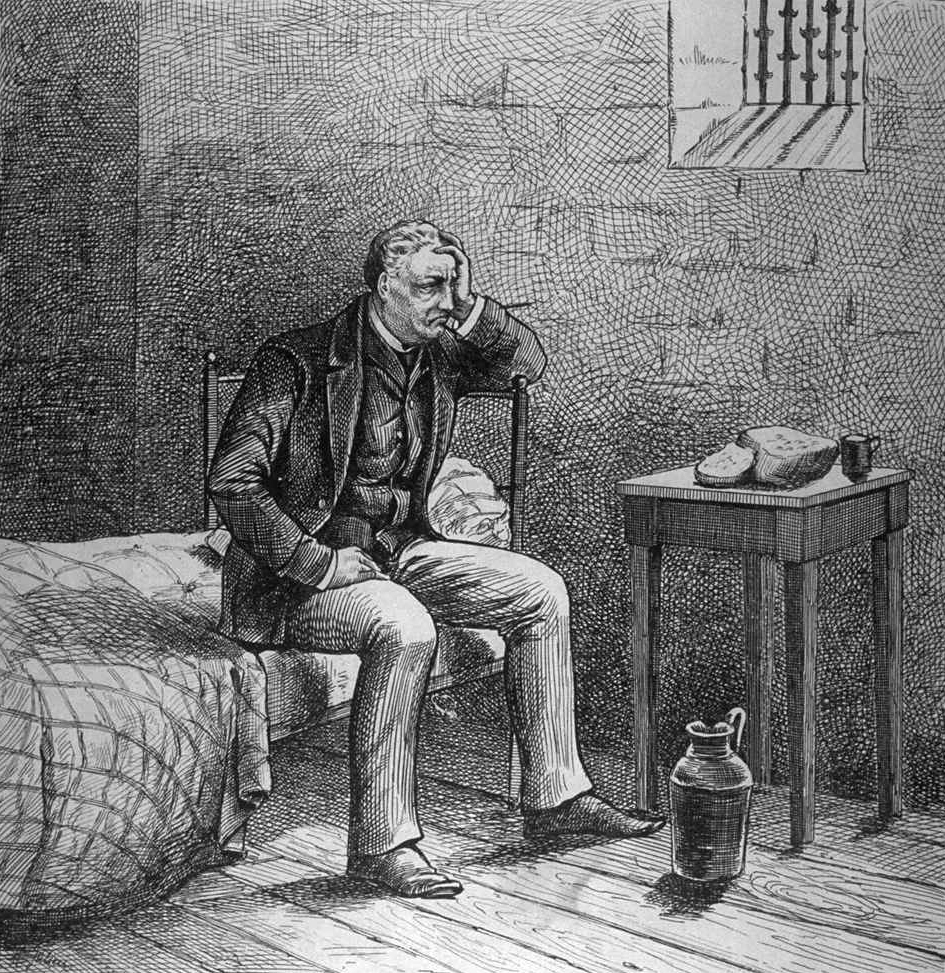

Julien was a remarkably versatile visual artist. His drawings of animals, particularly bison (1874–75), were outstanding. He could also sketch the daily lives of French Canadian farmers on the spot. His ethnological paintings and illustrations greatly contributed to his national and international reputation. His paintings would later be exhibited in London and New York, where he stayed for a brief period in 1884 to paint and exhibit. His major works were Tobogganing (1885); Départ de Québec du premier contingent canadien s’embarquant pour la guerre des Boers en Afrique du Sud (1899); Le patriote, also known by the name Le vieux de ‘37 (1904), which remains relevant in modern times, as it became the symbol of the Front de libération du Québec and is often still used in the centre of the Patriotes’ tricolour flag; Habitant fumant la pipe (1906); and La chasse-galerie (1906).

Julien often based his paintings on his sketches. Each of his drawings and paintings was done in a different style. He could switch from the most gothic style of romanticism (such as his scenes of tournaments) to quick, lively sketches in shades of red. His printmaking was accurate and animated, and his caricatures were full of curved lines — marking the beginning of the comic book culture that would become hugely influential in the following century. The scathing captions from his political cartoons were written just as ruthlessly as those of French caricaturist Honoré Victorin Daumier (1808–79), who was one of his many inspirations, not only for his drawings, but also for his piercing and subversive tone in the world of political satire.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom