The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was the forerunner of Canada's iconic Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Created after Confederation to police the frontier territories of the Canadian West, the NWMP ended the whiskey trade on the southern prairies and the violence that came with it. They helped the federal government suppress the North-West Resistance and brought order to the Klondike Gold Rush. The NWMP pioneered the enforcement of federal law in the West, and the Arctic, from 1873 until 1920.

Origins

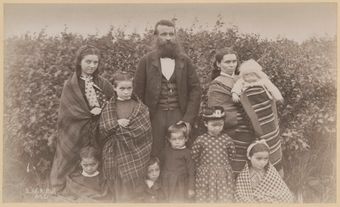

On 23 May 1873, the Canadian Parliament passed an act to establish “a Mounted Police Force for the North-West Territories.” Formerly known as Rupert’s Land, the domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the North-West Territories had been purchased by Canada in 1870. It included all of present-day Manitoba, and parts of Saskatchewan, Alberta and Canada’s northern territories. The vast region was populated by First Nations and Métis peoples, and a few white traders.

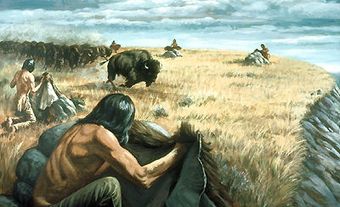

In Ottawa, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald wanted to send out a paramilitary force to secure Canadian sovereignty in the West and prepare the way for settlement. However, it was the whiskey trade that demanded immediate firm action. Traders from Fort Benton, Montana, had been operating illegal posts, such as the notorious Fort Whoop-Up in southern Alberta. They were tough adventurers, many of them veterans of the US Civil War, and even known desperadoes or outlaws. In exchange for bison (buffalo) hides from the Métis and First Nation peoples, they traded such merchandise as blankets, guns and ammunition. However, their most profitable commodity was alcohol. Nicknamed firewater, their whiskey was a potent concoction adulterated with such ingredients as Jamaica ginger, red peppers, chewing tobacco and laudanum.

Macdonald had received reports of the devastating effect of the whiskey trade on the Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood) and other First Nations. Lieutenant William F. Butler, a British army officer sent to investigate conditions on the frontier, wrote, “... the region of the Saskatchewan is without law, order, or security for life or property; robbery and murder for years have gone unpunished; Indian massacres are unchecked even in the close vicinity of the Hudson Bay Company's poste, and all civil and legal institutions are entirely unknown.” In June 1873, more than 30 Assiniboine were killed near a whiskey post in an incident known as the Cypress Hills Massacre.

First Recruits

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was modelled after the Royal Irish Constabulary. Macdonald initially called it the North-West Mounted Rifles, but changed Rifles to Police to avoid arousing American suspicions.

Reports from the West had stressed the symbolic importance of the traditional British army uniform among First Nations, so the NWMP adopted a scarlet tunic and blue trousers. Applicants had to be males between the ages of 18 and 40, of sound constitution and good character, able to read and write in either English or French, and ride a horse. Pay was 75 cents a day for sub-constables, and $1 for constables. Men from all walks of life applied, but many of those accepted had previous military or police experience.

In August 1873, the first 150 recruits went to Lower Fort Garry (now Winnipeg) where, under the force's first commissioner, George A. French, they were trained along the lines of a cavalry regiment. They were drilled in the use of revolvers and carbine rifles, and light field artillery. On French’s recommendation, an additional 150 recruits were sent to Lower Fort Garry the following spring.

The March West

On 8 July 1874, 300 officers and men of the NWMP set out from Dufferin, Manitoba, on a gruelling, two-month, 1,300-kilometre march across untracked prairie. Men and horses endured extreme weather conditions, hunger, foul water, illness, and hordes of mosquitoes and black flies before reaching La Roche Percee in southern Saskatchewan. There, the contingent split. Most of “A” Troop, under Inspector W.D. Jarvis, proceeded northwest to set up a police post at Fort Edmonton.

Meanwhile, French went south to Fort Benton to purchase supplies and fresh horses. Then he and Assistant Commissioner James F. Macleod led “B”, “C”, and “F” Troops, and the remainder of “A” westward. Their objective was Fort Whoop-Up. Métis scout Jerry Potts served as guide.

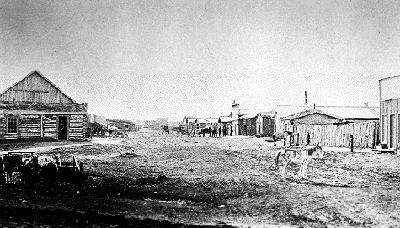

The Fort Whoop-Up outlaws had fled before the police arrived. Indigenous leaders like Siksika chief Isapo-muxika (Crowfoot) were pleased when the police arrested a few whiskey traders who were still in the area. The illicit trade had been quashed without a shot being fired.

First Nations Relations

For a decade and a half, the NWMP concentrated on building close relations with First Nations – ones that were complex, and not always beneficial to Indigenous people.

The police forged diplomatic links with the Blackfoot Confederacy, which included a friendship between James Macleod and Isapo-muxika. Such relations allowed the NWMP to play an essential role in convincing Indigenous leaders to sign treaties with the Canadian government and move their people onto reserves. (See Numbered Treaties.) Those treaties required First Nations to give up vast tracts of territory and their traditional way of life, reducing them to a state of dependency on the government. Afterwards, the NWMP also failed to protect Indigenous interests amid the oncoming tide of white settlement, and the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

However, the establishment of police posts like Fort Macleod ended Canada’s brief “Wild West” period, which had caused great harm to Indigenous communities. As Isapo-muxika said at the signing of Treaty 7 in 1877: “If the police had not come to this country, where would we all be now? Bad men and whiskey were killing us so fast that very few of us would have been alive today. The Mounted Police have protected us as the feathers of the bird protect it from the frosts of winter. I wish them all good, and I trust that all our hearts will increase in goodness from this time forward."

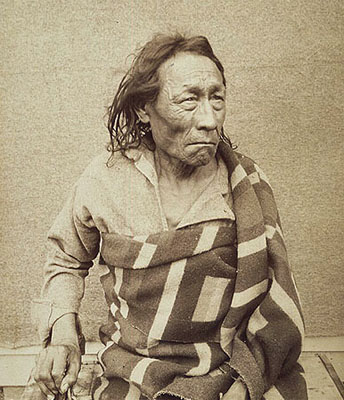

NWMP policies towards First Nations also contrasted sharply with those of the United States Army south of the border, where there was open war with Indigenous people. In 1876, after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the US, thousands of Sioux followers of chief Tatanka-Iyotanka (Sitting Bull) sought refuge in Canada rather than surrender to American soldiers. The NWMP then defused a potentially volatile diplomatic crisis, and played a role in convincing the American Sioux to eventually return to the US.

North-West Resistance

In the early 1880s, unrest smoldered among the Métis and on reserves due to the disappearance of the bison herds, crop failures, the overbearing manner of Canadian Pacific Railway surveyors, and disenchantment with the government in Ottawa. NWMP strength was increased to 500 men, but that was insufficient for growing responsibilities, which now included a limited role in southern British Columbia. Ottawa ignored the NWMP's warnings of potential trouble in the Saskatchewan Valley if grievances were not addressed.

In 1885, under the leadership of Louis Riel and with the support of the Cree chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), the Métis rebelled against the Canadian government, taking up arms in a violent insurgency. The fighting that followed killed hundreds of people, including eight NWMP constables, before the North-West Resistance was crushed by the police and federal troops. The defeat of the rebels — and the subsequent hanging of Riel — marked the subjugation of the Métis and Plains First Nations by Ottawa, and the permanent enforcement of Canadian law in the West.

Law and Order

After the resistance, the government increased the NWMP to 1,000 men and appointed Commissioner Lawrence Herchmer to modernize the force. Herchmer improved training and enhanced methods of crime prevention, therefore preparing the police to cope with the coming waves of settlers.

The police performed a wide array of civic duties, from serving as postmasters to customs collectors. They rescued lost children and retrieved missing livestock. NWMP surgeons often tended to civilians. The constables enforced the law and kept the public peace in white communities and on reserves. NWMP investigators solved crimes like robbery and murder, and were effective in breaking up rustler gangs operating along the international border.

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government, elected in 1896, wanted to disband the NWMP on the grounds that it had outlived its usefulness. However, that idea was unpopular in the West where the murders of Sergeant William Wilde and Sergeant Colin Colebrook — by (respectively) the Kainai warrior Si’k-okskitsis (Charcoal) and a Cree youth Kitchi‑manito‑waya (Almighty Voice) — stoked fears of an “uprising.” Meanwhile, another significant event far to the north proved the necessity of maintaining the NWMP.

Klondike and Arctic Expansion

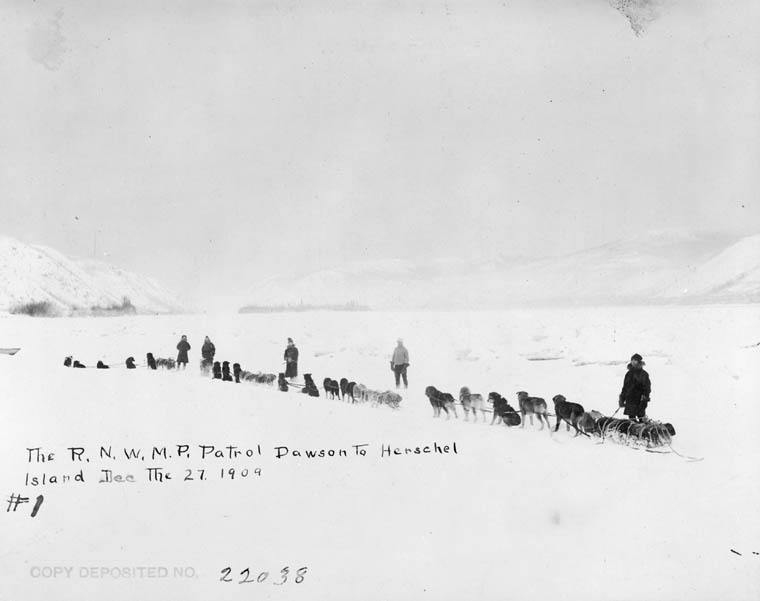

Inspector Charles Constantine had already established an NWMP post near the Yukon community of Forty Mile, when, in 1896, news of a major gold strike on the Klondike River touched off a stampede of fortune seekers to the North. The NWMP quickly set up checkpoints on the routes to Dawson City, the gold rush capital.

Their strict enforcement of regulations — including the NWMP's requirement that prospectors bring enough provisions to last them a year on the Klondike — prevented many fortune seekers from dying by exposure and starvation. Criminals from Skagway, Alaska, were denied entry. The Klondike Gold Rush was orderly and relatively crime-free. (See Gold Rushes in Canada.)

Did you know?

The NWMP began to hire women as matrons or jailers to help with female prisoners starting in the 1890s. One of these women was “Klondike Kate” (Katherine Ryan), who became the NWMP’s first special constable in the North-west Territories in 1900.

In 1900, after the gold rush had ended, the NWMP expanded its authority north of the Arctic Circle and in 1903 established the first Arctic police post at Fort McPherson. By now the force was internationally famous. An NWMP detachment had represented Canada in London at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Further contingents would participate in the coronations of King Edward VII and King George V. In 1904, the Force was granted the prefix Royal, and became known as the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP).

RCMP Established

During the First World War, members of the RNWMP were exempted from military service because they were needed on the home front to discourage acts of enemy sabotage. In 1920, the RNWMP merged with the Dominion Police to form the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom