The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was created on 4 April 1949. It was Canada’s first peacetime military alliance. It placed the country in a defensive security arrangement with the United States, Britain, and Western Europe. (The other nine founding nations were France, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Italy.) During the Cold War, NATO forces provided a frontline deterrence against the Soviet Union and its satellite states. More recently, the organization has pursued global peace and security while asserting its members’ strategic interests in the campaign against Islamic terrorism. As of 2021, there were 30 member countries in NATO.

Advent of Cold War

In 1947, at the beginning of the Cold War and in the aftermath of the Second World War, the Soviet Union (USSR) created a buffer zone in Eastern Europe between itself and the West. It did so by pursuing a policy of aggressive military expansion at home and subversion abroad. It imposed its will on East Germany, Poland and other nations along the Soviet border. This was the source of much concern in Ottawa and other Western capitals. There was real fear that France, Italy or other nations might become Communist and eventually ally themselves with the Soviets.

The problem was complicated by what Ottawa saw as a resurgent isolationism in the United States; as well as an unwillingness in the US Congress to pick up the international burdens that France and Britain, both weakened by the Second World War, could no longer bear. The answer seemed to lie in an arrangement that would link the democracies on both sides of the Atlantic into a defensive alliance. This would protect western Europe from attack while involving the US firmly in world affairs. A further advantage for Ottawa was that such an arrangement might bind together all of Canada’s trading partners. It therefore offered potential economic benefits as well. (See also General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.)

Founding

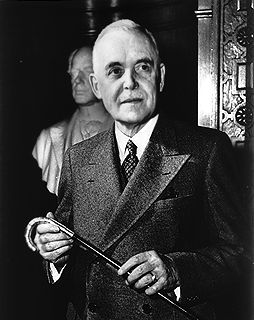

The first public expression of this thinking in Canada came from Escott Reid at the Couchiching Conference on 13 August 1947. Reid was a civil servant at the Department of External Affairs (now Global Affairs Canada). Other Canadians, including External Affairs Minister Louis St-Laurent, picked up the idea. It was soon discussed in Washington and London. Secret talks between the British, Americans and Canadians followed. These led to formal negotiations for a broader alliance in late 1948; by that time, St-Laurent was prime minister.

Canada’s representative at the negotiations was Hume Wrong. He was ambassador to the US and a hardheaded realist. Wrong believed any treaty should be for defence alone; this view was popular among the other participants. A provision supporting Ottawa’s wish for economic ties (an idea promoted by Reid and Canada’s new foreign minister, Lester Pearson), was included in the treaty; but little came of it in practice.

The treaty was signed on 4 April 1949. It included 12 nations: Canada, United States, Iceland, Britain, France, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Italy. At the core of the treaty was the collective security provision of Article 5; that “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.”

Korea and Europe

NATO existed largely as a paper alliance until the Korean War (1950–53). That led the NATO states — many of them fighting in Korea under the banner of the United Nations — to build up their military forces. For Canada, this had major consequences, including a huge increase in the defence budget and, eventually, the return of troops to Europe.

By the mid-1950s, about 10,000 Canadian troops were stationed in France and West Germany. They included an infantry brigade group and an air division. The Canadian contribution was small compared to the larger NATO members, but its quality was widely considered to be second to none. In 1955, a rearmed West Germany was also admitted as a NATO member.

By the late 1960s, high defence costs, plus the equipping of Canadian jets and other forces with US-supplied nuclear weapons, fed criticism at home about Canada’s role in NATO and its alleged subservience to US policy. By 1966, France had pulled out of NATO’s military structure, although it remained a member of the alliance.

The government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau considered a similar withdrawal for Canada. In 1969, after a major review of foreign policy, it decided instead to cut Canada’s contribution drastically; it ended the country’s nuclear strike role and reduced the army and air elements. At this point onward, Canadian commitment of arms and troops to the alliance remained substantially lower than other NATO partners wished.

Cold War Ends

As the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, Canada’s remaining troops in Europe were brought home. NATO then changed its focus from collective defence against the Soviet Union, to a wider pursuit of global peace and security. Canada was a strong supporter of NATO’s reform and expansion; it asserted that the alliance was finally embodying the ideals, such as international co-operation, for which it had been established.

One of the first crises to confront NATO in this new era was the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. This led to civil war and sectarian fighting in the Balkans. NATO became a partner of the United Nations’ various interventions in the region. The lines between peacekeeping and war-fighting became blurred. In 1995, NATO aircraft started bombing Serbian-held areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Operation Deliberate Force. In 1999, NATO forces (including Canadian combat aircraft) launched a 78-day air campaign to stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo and oust Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic. (See Canadian Peacekeepers in the Balkans.) In 2001, NATO also intervened in Macedonia.

Throughout this period, Canada sent thousands of military personnel to the region as part of both NATO and UN forces; 23 Canadian Forces members died in the Balkans missions. The end of the Cold War also marked the unification of Germany. In 1999, NATO admitted Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary — three nations once under Soviet control.

Fight Against Terrorism

The alliance's priorities evolved with global developments. The day after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on Washington, DC, and New York, NATO invoked the Article 5 “collective defence” clause for the first time in its history.

The US subsequently invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 because its government was sheltering Osama bin Laden. In 2003, NATO assumed leadership of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). This was a United Nations-mandated force that grew to include more than 40 NATO and non-NATO members. The force was tasked first with securing Kabul, and later other parts of Afghanistan. It was the first time NATO had undertaken a mission so far from Europe.

Canadian forces fought in Afghanistan from the start. Canadian special forces were involved in the 2001 invasion. In 2003, more than 700 Canadian troops under ISAF command provided security in Kabul. In 2006, a Canadian Army battle group fought under ISAF in the Kandahar area. Most Canadian forces left the country in 2014; by that time, 158 Canadians had died in Afghanistan.

In 2011, Canada sent fighter jets to Libya as part of NATO’s bombing operation against Moammar Gadhafi’s regime.

Expansion

At the NATO Prague Summit of 21–22 November 2002, member nations agreed to make changes to ensure that the alliance remained a central mechanism for meeting its members’ security needs. This involved expanding the organization with new members, enhancing relationships with NATO’s partner countries, and giving the alliance new capabilities.

As of 2021, NATO had grown to include 30 members. In addition to the founding 12 countries, the member countries are (with year of admission): Greece and Turkey (1952); Germany (1955); Spain (1982); the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland (1999); Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia (2004); Albania and Croatia (2009); Montenegro (2017); and North Macedonia (2020).

Canada has participated in every NATO mission since the alliance’s creation. In recent years, Canada has funded about 5.9 per cent of NATO’s budget.

See also Canada and the Cold War; NORAD; Middle Power; Defence Policy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom