Early Life and Career

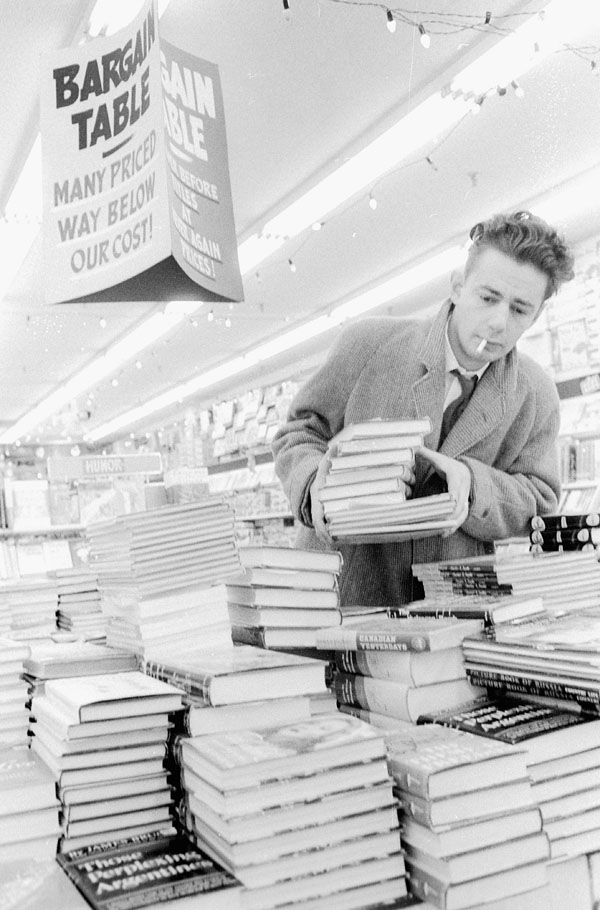

Richler’s voice came early in his career, but not with his first books. After graduating without distinction from Baron Byng high school on St. Urbain Street, he lasted less than two years at Sir George Williams College (later Concordia University). By age 19 he was off to Europe for a traditional writer’s education in life, and enjoyed, between 1949 and 1952, his fair share of formative misadventures in Spain, Paris and London. By 1954 he was settled in London and had already published his first novel, The Acrobats. It was very serious, very dark, and though the work of such an evidently talented young man that it was soon published in several countries, it bore little resemblance to the mature artist. The same was true of Richler’s second and third novels, of which Son of a Smaller Hero (1955) managed to infuriate and alienate most of his large family in Montréal, as well as a considerable percentage of the city’s Jewish community. Only with his fourth novel, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, published in 1959, did he learn how to translate his ferocious, satiric, funny take on human behaviour onto the page. With this novel, and its anti-hero, the hard-nosed, unscrupulous, but also energized and empathetic young hustler, Duddy Kravitz, Richler gave Canadian literature one of its most challenging and unresolved protagonists, and one of its first important novels. It won him admirers in London, New York and Toronto, but not so many, it often seemed, among his “people” in Montréal — a pattern that would persist for decades.

Though two lengthy excerpts from Duddy Kravitz ran in Maclean’s, the novel’s initial impact in Canada was minimal. This spoke more to the somnambulant state of Canadian literary culture at the time, and was one reason why Richler continued to live in London, where he both began a large family with his second wife, Florence Richler, née Wood, whom he married in 1960, and maintained a robust and impressive career as a freelance journalist and scriptwriter for radio, television and film. He and Florence did not repatriate permanently with their five children until 1972, and did so to a Canada then in the thrall of a determined cultural awakening, a period now known as the era of cultural nationalism. While predictably a critic of the movement, Richler both helped define the new literary Canada, and benefited from its unfolding.

Canadian Literature Comes of Age

During the 1960s, however, Richler’s evolution as a novelist took a near-wrong turn. Overcommitted to other projects, uncertain how to proceed artistically, he kept putting aside the fiction that would eventually inaugurate his major period, St. Urbain’s Horseman, in favour of smaller, sharper works. Both The Incomparable Atuk (1963) and Cocksure (1968) are satires of insight and ferocity, as well as caustic, at times surreal wit. And yet, by steering clear of his home turf of Jewish Montréal, they lack the depth and humanity that he found when engaging, however combatively, with the material he knew best. A 1969 collection of stories, The Street, many closer to autobiographical sketches, announced his intention to re-establish his literary roots in Montréal, an intention that came to quick, brilliant fruition with the publication of the sprawling, deeply felt St. Urbain’s Horseman in 1971. Literary historians count the book’s simultaneous publication in Canada, the United States and England as the day the nation’s literature achieved adult status. St. Urbain’s Horseman, which won Richler his second Governor General’s Award, was also nominated for the newly established Booker Prize in London.

The Major Period

With St. Urbain’s Horseman, his seventh novel, Mordecai Richler settled into the rhythm of taking many years between major books. He filled in the gaps with his usual abundance of scripts, journalism, compiling and editing anthologies, along with a perhaps unlikely sidebar — writing for children. Jacob Two-Two Meets the Hooded Fang (1975) may have begun as a tale told to his youngest son, but it quickly achieved the status of a Canadian classic. Twice the short novel was made into a film, and twice more Richler revisited his beloved character in print. He also successfully adapted each novel for the stage. In 1974, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, by now a well-taught text in Canadian high schools, was also turned into a successful film, another modest milestone in the fraught emergence of an English Canadian film industry. Novel-wise, Richler once again temporarily put aside a more ambitious book he had been mulling over to quickly write, and happily publish, the scabrous Joshua Then and Now (1980). It, too, made it to the movies, albeit with less success. Finally, in 1989 the novel Solomon Gursky Was Here shocked and unsettled the Canadian literary scene with everything from its nine plot lines spread over a two hundred year span, its outrageous Jewish rewrite of a treasured pseudo-Canadian failure story — the doomed Franklin expedition to find the Northwest Passage — and its not-so-concealed portrait of a notorious bootlegging turned distillery moguls clan, the Gurskys, clearly modelled on the Bronfmans. The book, the product of a lifetime of experience and craft, and arguably Richler’s masterpiece, was received with maximum attention in Canada but, perhaps, a somewhat lesser degree of ardour. In England, it was shortlisted again for the now highly influential Booker, but failed to take the prize.

By the time he published Solomon Gursky, Richler was a household name in Canada. Often that name was being taken in vain, especially in French-speaking Québec, where his status as a biting and mocking commentator on aspects of the nationalist movement, in particular the language and sign laws introduced in the late 1980s, earned him much enmity. In contrast, for English-speaking Canadians, most piquantly for Jewish Montrealers, many in their fourth decade nursing a grudge against their most famous offspring, he became a kind of reluctant hero, standing up for their community, their city, and for a united Canada, in his own candid, irascible way. Reams of journalism came out of his powerful, bare-knuckled engagement with Québec nationalism, most famously his 1991 New Yorker piece, and the quick, cutting book that grew out of it. Oh Canada! Oh Quebec! (1992)is far from his best non-fiction. It is, however, arguably one of the most influential works ever published in the country.

The Final Decade

In his final decade, the now-veteran novelist produced one very good travel book, 1994’s This Year in Jerusalem, and the charming novel that appears, at present, to be the people’s choice among his works. On its appearance in 1997, Barney’s Version became an instant bestseller and, shortly, winner of the Giller Prize, a still relatively new literary award that Richler had himself helped set up a few years earlier. The tale of the outsized, unapologetic, apostate Jew Barney Panofsky was presumed by many to be closely autobiographical. It isn’t, most significantly its portrait of a man who destroys his one great chance at enduring love, but much about the character’s appetite for life, and his philosophy for living, is close to its author’s way of being in the world. New, almost, to Barney’s Version was a degree of pathos, and an emotional tenderness, that won Richler new readers and admirers in what was his fifth and, it turned out, final decade of a significant career as a man of letters and that loyal member of the opposition. His death in 2001 was mourned nationally.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom