Family Background

Montgomery’s ancestors were among the wealthy and educated immigrants who came to St. John’s Island (now Prince Edward Island) from Scotland in the 1770s. (See Scottish Canadians.) Her maternal great-grandfather, William Simpson Macneill, was a member of the provincial legislature from 1814 to 1838. He also served as Speaker of the House of Assembly. Her paternal grandfather, Donald Montgomery, served in the provincial legislature from 1832 to 1874. He was appointed to the Senate by Sir John A. Macdonald and served there from 1873 to 1893.

Early Life and Education

Montgomery’s mother, Clara Woolner Macneill, died from tuberculosis in 1876 at the age of 23. Montgomery was not yet two. Her earliest memory was of seeing her mother in her coffin, as she wrote in her multi-volume autobiography The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career, published in 1917.

I did not feel any sorrow, for I knew nothing of what it all meant. I was only vaguely troubled. Why was Mother so still? And why was Father crying? I reached down and laid my baby hand against Mother's cheek. Even yet I can feel the coldness of that touch.

Montgomery’s childhood was spent with her maternal grandparents in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island. Her father, Hugh John Montgomery (1841–1900), moved west to Prince Albert, North-West Territories (now Saskatchewan) in 1887. Maud was still a child. She joined her father and his new family in 1890. However, she felt homesick and disheartened by her marginal position in her father’s new home and had a strained relationship with his new wife.

Montgomery returned to the Macneill homestead in 1891. She also spent time throughout her childhood with her extended maternal family and her paternal grandfather. They all lived in nearby Park Corner, PEI. However, her grandparents showed her little affection. Her childhood was predominantly one of loneliness and isolation, feelings that would remain with her throughout her life. She coped by escaping into her imagination, which she nurtured with copious amounts of reading and writing.

Early Career

Montgomery once wrote in her journals, “I cannot remember a time when I was not writing, or when I did not mean to be an author. To write has always been my central purpose around which every effort and hope and ambition of my life has grouped itself.” She began writing poetry and keeping journals when she was nine, and started writing short stories in her mid-teens. She published them first in local newspapers and then sold them with considerable success to magazines throughout North America.

Her first publication, a poem titled “On Cape Le Force,” was printed in the Charlottetown Patriot on 26 November 1890, only a few days before her 16th birthday. She was still living in Prince Albert at the time. She initially used pseudonyms, such as Maud Cavendish or Joyce Cavendish, to conceal her professional ambitions. She finally settled on L.M. Montgomery in order to hide her gender.

In 1894, she completed a teachers’ training course at Prince of Wales College in Charlottetown. She graduated from the two-year program with honours after only one year. She also studied English literature (1895–96) at the Halifax Ladies’ College at Dalhousie College (now Dalhousie University). For financial reasons, she chose to study there for only a year and did not complete a degree. It was during this time that she was first paid for her writing.

She taught in village schools in Belmont and Lower Bedeque, PEI, in the late-1890s. But she was soon earning enough from her writing that, following the death of her grandfather in 1898, she returned to Cavendish to live with her grandmother. In the winter of 1901–02, she worked as a proofreader for the Daily Echo in Halifax. She also wrote a weekly society column under the alias “Cynthia.” She otherwise spent the period between 1898 and 1911 in Cavendish, where she prolifically wrote poems and stories for publication. She also worked in the local post office, which was run by the Macneills from their homestead.

Personal Life and Romantic Prospects

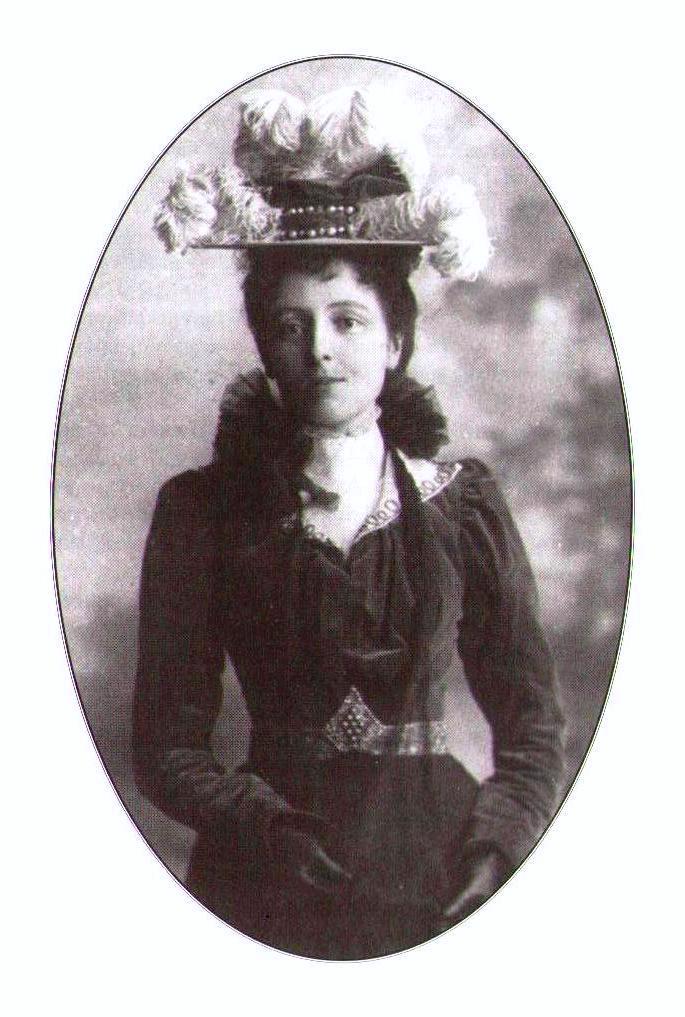

Slim, striking and highly intelligent, Montgomery drew the attention of numerous suitors in her youth. She had several romantic relationships, some of which informed her fiction. In her teen years in Cavendish, she declined a marriage proposal from a boy named Nate Lockhart. During her post-secondary studies, she was courted by one of her teachers, John A. Mustard, and also by Will Pritchard, the brother of her friend Laura Pritchard. Montgomery remained friends with Pritchard, corresponding with him until his death from influenza in 1897.

Also in 1897, Montgomery became secretly engaged to Edwin Simpson, a distant cousin who was studying to become a Baptist minister. However, within a year, she became embroiled in a passionate romance with Hermann Leard, a farmer in Bedeque, PEI. She broke off her engagement with Simpson, much to her family’s dismay. In 1899, shortly after Montgomery returned to Cavendish to live with her grandmother, Leard died from influenza. Montgomery’s interest in romantic love seemingly died with him.

Marriage and Family Life

On 5 July 1911, shortly after her grandmother’s death, Montgomery married Presbyterian minister Ewen Macdonald. She had been secretly engaged to him since late-1906. They were married in Park Corner and honeymooned in Scotland and England. They then left Prince Edward Island later in 1911 to take up residence in Leaskdale, Ontario, where Ewen was assigned a parish. Maud and Ewen’s first son, Chester, was born in 1912. A second son, Hugh, was stillborn in 1914. The third, Stuart, was born in 1915.

Maud and Ewen remained in Ontario with Chester and Stuart. In 1926, they moved to the small village of Norval. In 1935, they relocated to Toronto, where they lived in a house near the Humber River that Maud dubbed “Journey’s End.”

Montgomery’s roles as mother and minister’s wife made many demands on her time. The situation was exacerbated by Ewen’s increasingly unstable mental health. He was admitted to a sanatorium in 1934 and resigned from his parish in Norval in 1935. Montgomery herself suffered from mental illness. She continually sought to find a balance between her writing and her domestic responsibilities. She repeatedly demonstrated in her writing and in interviews that she believed motherhood to be the most important work for women. This sentiment indicates both her engagement with early 20th-century ideas about a woman’s maternal duty and her sense of her own unhappiness due to the early loss of her mother.

Anne of Green Gables (1908)

Montgomery completed her first novel, Anne of Green Gables, in 1905. It was inspired by such children’s books as Little Women and Alice in Wonderland, and by a newspaper story Montgomery read about an English couple who had arranged to adopt a boy but were sent a girl. The manuscript was rejected by every publisher she sent it to, so she gave up and kept it in a hat box. In 1907, she tried again and secured a publishing deal with L.C. Page in Boston.

Released in June 1908, the book sold more than 19,000 copies in its first five months. It was reprinted 10 times in its first year. It garnered widespread acclaim, including endorsements from Canadian poet Bliss Carman and American author Mark Twain, who called Anne Shirley “the dearest, most moving and delightful child since the immortal Alice.”

Montgomery’s contract with her first publisher, L.C. Page, required her to produce two sequels to Anne of Green Gables — Anne of Avonlea (1909) and Anne of the Island (1915). She then wrote four more books under contract to Page: Kilmeny of the Orchard (1910), The Story Girl (1911), Chronicles of Avonlea (1912) and The Golden Road (1913).

By the end of the First World War, Lucy Maud Montgomery was a household name throughout the English-speaking world. In 1920, although Montgomery had not renewed her contract with him, Page published a collection of short stories, Further Chronicles of Avonlea, that were still in his possession. A lawsuit ensued that more or less ended Montgomery’s relationship with the publisher. By this time, Page held the rights to her first six books, including Anne of Green Gables. Montgomery shifted to Canadian publishers McClelland and Stewart and American publishers Frederick Stokes in 1917. In the ensuing decade, she engaged in a series of bitter lawsuits and countersuits with Page over royalties and rights.

This episode of The Secret Life of Canada looks into the life of Lucy Maud (L.M.) Montgomery, creator of iconic characters like Anne of Green Gables and Emily of New Moon. The lesser-known story is that of the writer herself, who had many struggles within her own life, especially with her mental health.Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Other Notable Publications

With McClelland and Stewart and Stokes, Montgomery wrote five more Anne books: Anne's House of Dreams (1917), Rainbow Valley (1919), Rilla of Ingleside (1920), Anne of Windy Poplars (1936) and Anne of Ingleside (1939). They also published her bestselling Emily trilogy — Emily of New Moon (1923), Emily Climbs (1925) and Emily’s Quest (1927) — as well as six other novels: The Blue Castle (1926), Magic for Marigold (1929), A Tangled Web (1931), Pat of Silver Bush (1933), Mistress Pat (1935) and Jane of Lantern Hill (1937).

By the time she died, Montgomery had published 20 novels and two books of short stories, as well as one book of poetry (The Watchman and Other Poems in 1916), a brief autobiographical account (The Alpine Path: the Story of My Career in 1917), and the many poems, stories and articles she wrote for magazines throughout her life. Most of these were published in anthologies after her death.

Thematic Concerns

Montgomery’s fiction returns again and again to representations and narratives related to questions of motherhood and maternity. Her novels and stories repeatedly focus on orphans, children abandoned by parents or separated from them, and children in the care of unloving relations, as well as absent mothers and childless women or “spinsters.” Much of Montgomery’s writing — from the first novel, Anne of Green Gables, to such late novels as Magic for Marigold and Jane of Lantern Hill — regards motherhood as crucial work for women and focuses primarily on the education of girls.

Business Affairs and Legal Issues

Following several lawsuits against her first publisher, L.C. Page, Montgomery eventually became an astute businesswoman. She ensured a stable and solid income from her work, which enabled her to maintain a comfortable life for her family — a remarkable achievement for a female writer in the early 20th century. She did not, however, significantly profit from the sale of her first books, particularly Anne of Green Gables. The royalties she was assigned in her first contract with Page were small. The profits pertaining to licensing and reprints, including the fees for the first two cinematic adaptations of the novel in 1919 and 1934, remained for the most part with the publisher.

In the decades since Montgomery’s death, a thriving industry consisting of television series, stage productions, and Anne-related commodities such as souvenirs and dolls has flourished, as has the steady popularity of Montgomery’s books. The licensing, broadcasting and merchandising rights to Anne of Green Gables have become highly profitable. They have been the subject of numerous legal disputes over the years. All licensing rights are held jointly by Montgomery’s heirs and the province of Prince Edward Island through the Anne of Green Gables Licensing Authority Inc.

Adaptations

Montgomery’s work has been adapted dozens of times and translated into more than 36 languages. Anne of Green Gables alone has been adapted more than two dozen times, including twice as a Hollywood feature (a silent film in 1919 and a talkie in 1934) and twice as a BBC miniseries (in 1952 and 1972). It was adapted into a musical for CBC TV by Don Harron, Norman Campbell and Phil Nimmons in 1956. A second production aired in 1958. In 1965, Harron, Campbell and Mavor Moore expanded the TV version into a full-length musical for the Charlottetown Festival. Anne of Green Gables: The Musical premiered at Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre of the Arts on 27 July 1965. It has played there every year since, earning the Guinness World Record for “longest running annual musical theatre production.”

However, the best-known adaptation of Anne of Green Gables is Kevin Sullivan’s 1985 CBC TV miniseries starring Megan Follows, Colleen Dewhurst, Richard Farnsworth and Jonathan Crombie. It went on to win nine Gemini Awards, an Emmy Award and a Peabody Award. The initial broadcast of the miniseries was the highest-rated television drama in Canadian history. Part 1 drew 4.9 million viewers and Part 2 attracted 5.2 million — the largest audience for non-hockey broadcasts in CBC history. Its success led to three sequels, all produced by Sullivan: Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel (1986) and Anne of Green Gables: The Continuing Story (2000) were produced by CBC and feature the same cast; Anne of Green Gables: A new Beginning (2008) was produced by CTV and stars Barbara Hershey as a middle-aged Anne.

The CBC has since developed a veritable cottage industry of Montgomery-related period pieces. The most successful is the multiple Emmy Award- and Gemini Award-winning Road to Avonlea (1989–96). It is loosely based on a number of Montgomery’s books and stars a young Sarah Polley as protagonist Sara Stanley. The series averaged nearly two million viewers in the 1989–90 season, making it the most-watched Canadian TV series until Canadian Idol in 2003. The CBC also produced Emily of New Moon (1998–2000), based on the Emily series of novels, and Anne with an E (2017–19), a somewhat darker take on the Green Gables story. It stars Amybeth McNulty, Geraldine James and R.H. Thomson and is available internationally through Netflix.

American public broadcaster PBS produced a trio of TV movie adaptations of Green Gables co-starring Martin Sheen as Matthew Cuthbert: Anne of Green Gables (2016), Fire & Dew (2017) and The Good Stars (2017). Kevin Sullivan produced an animated adaptation for PBS in 2000. Two successful animated versions of Green Gables have also been produced in Japan, one in 1979 and the other in 2009. In 2016, Rachel McAdams narrated an audiobook of Anne of Green Gables for audible.com.

Montgomery’s 1926 novel The Blue Castle, which was banned by some libraries for depicting the life of an unwed mother and for analyzing religious hypocrisy, was adapted into a hit musical in Poland in the 1980s.

Death and Mental Health

Considerable controversy and speculation have surrounded the circumstances of Montgomery’s death. She died in Toronto in 1942, just before the first Canadian edition of Anne of Green Gables was published by Ryerson Press. Her body was transported by train to Prince Edward Island. A funeral ceremony was held at what had by then become Prince Edward Island National Park, the homestead in Cavendish that Montgomery had said was a model for Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert’s farm in the first novel. Montgomery was buried in Cavendish.

In 2008, on the 100th anniversary of the publication of Anne of Green Gables, Montgomery’s granddaughter, Kate Macdonald Butler, revealed in the Globe and Mail that, from the start, her family believed Montgomery’s death had not been due to heart failure, as originally disclosed, but rather had been a suicide by drug overdose. She explained that her father — Montgomery’s youngest son, Stuart Macdonald — had found a note by his mother’s bedside asking for “forgiveness.” This note had been kept secret by the family ever since. Macdonald Butler stated that the family’s motive for coming forward with the news was to help lift some of the stigma surrounding mental illness. She noted that Montgomery, like her husband Ewen, also suffered from depression, and that “she was isolated, sad and filled with worry and dread for much of her life.” This was especially true in her later years when Ewen’s condition was more pronounced.

Macdonald Butler’s disclosure was applauded by many mental health groups. Reid Burke of the Canadian Mental Health Association in PEI said that it was “very positive to see her stepping forward, making sure that people understand that this is not a new issue. This is an issue that people dealt with for years… There is that kind of myth that if you don’t talk about it, it will go away. And it doesn’t go away. It affects families and the survivors for years.”

Lucy Maud Montgomery’s final note:

I have lost my mind by spells and I do not dare think what I may do in those spells. May God forgive me and I hope everyone else will forgive me even if they cannot understand. My position is too awful to endure and nobody realizes it. What an end to a life in which I tried always to do my best in spite of many mistakes.

However, University of Guelph professor Mary Rubio, a leading authority on Montgomery and her work, offered a different take. She argued that the note, which was written on the back of a royalty statement dated two days before Montgomery’s death, cannot conclusively be interpreted as a suicide note. She believes it may in fact be the last page of a journal entry. Rubio co-edited Montgomery’s multi-volume journals published between 1985 and 2004. She believes that the number “176,” written at the top of the note, indicates that it was page 176 in a handwritten journal, which Montgomery would have intended to transcribe by typewriter, as was her custom. Rubio has argued that the missing 175 pages, which have never been found, may have been taken by Montgomery’s eldest son, Chester Macdonald. A ne’er-do-well who lived in Montgomery’s basement, Chester’s dependency and cruelty reportedly exacerbated his mother’s poor mental health.

But Rubio has also conceded that Montgomery was “suffering unbearable psychological pain,” that she had developed a dependency on barbiturates, and that she had told a friend a month before her death that “she had doubts that she would still be there in a week.” In her biography, Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings (2008), Rubio writes that “Maud’s comment… tips the evidence in the direction of a premeditated death by someone who was in the grip of a major depressive episode, and may or may not have understood that she was dependent on drugs that were killing her.”

Heritage Sites and Landmarks

Montgomery maintained that she wanted to preserve a clear separation between her fiction and her life. But the two have come to be inextricably entwined via the various heritage and tourist sites associated with Montgomery and her work. Thousands of tourists visit Prince Edward Island each year to see the “sacred sites” related to the writing of Anne of Green Gables and its imaginative landscape.

In 1983, the City of Toronto named a park near Montgomery’s Toronto home in her honour. Montgomery’s home in Leaksdale, Ontario, and the Green Gables area around her Cavendish home in PEI, were named National Historic Sites by the federal government in 1997 and 2004, respectively. (The latter was first made open to the public in 1985.) In 2017, the manse in Norval, Ontario, where Montgomery lived with her family until 1935, was purchased by the L.M. Montgomery Heritage Society of Halton Hills. It plans to turn the home into a museum.

Artistic and Critical Legacy

Montgomery’s novels remain in print. They continue to be the focus of increasing critical and scholarly attention, as do her life, journals, and the international cultural impact of her work. A 2014 reader poll conducted by CBC Books declared Anne Shirley as Canada’s most iconic fictional character. Mary Rubio has called Anne of Green Gables “Canada’s most enduring literary export.” A 2003 BBC survey called The Big Read aimed to determine Britain’s best-loved novel. It ranked Anne of Green Gables at No. 41, ahead of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. In 2012, Anne was ranked No. 9 in a survey of children’s novels by the US-based School Library Journal.

However, Montgomery experienced considerable artistic anxiety early in her career and throughout her life. She felt her work was perceived to be less literary and less modern than the writing of many of her contemporaries, something even her extraordinary international popularity did little to assuage. She was also disappointed that her poetry, which she continued to write and publish her whole life, was not taken as seriously as her fiction. She considered her poetry to be more significant than her novels, which she sometimes characterized as “potboilers.”

Following the publication of some of Montgomery’s childhood letters in The Years Before “Anne” in 1974, and a collection of letters to her Scottish friend G.B. MacMillan, My Dear Mr. M: Letters to G.B. MacMillan from L.M. Montgomery, in 1978, second-wave feminists such as Margaret Atwood began to champion Montgomery’s literature as more than mere children’s fiction or genre writing. Montgomery, and especially the character of Anne Shirley, came to be seen as feminist heroes ahead of their time, representing a movement before there was a name for it. As the Guardian’s Jean Hannah Edelstein wrote in 2009, “It’s never stated explicitly, but Anne is definitely a feminist, and being a feminist in early 20th-century Canada is a difficult path to follow.” Moira Walley-Beckett, executive producer of the 2017 adaption Anne with an E, told the CBC that, “Anne’s issues are contemporary issues: feminism, prejudice, bullying and a desire to belong.” In 2016, Slate declared Anne “a patron saint of female outsiders.”

The publication of the first of Montgomery’s journals in 1985 (edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston) further revealed the mature, complicated and sometimes troubled mind of the author. It also encouraged deeper analysis and complex interpretations of her fiction. In 1993, the University of Prince Edward Island founded the L.M. Montgomery Institute, which hosted the International L.M. Montgomery Conference in 1994. The biennial event attracts hundreds of academics and fans from around the world. It has resulted in the publication of numerous essays, dissertations and collections analyzing Montgomery’s work. Her handwritten journals and scrapbooks, along with original manuscripts, photographs and personal effects, are held at the University of Guelph’s L.M. Montgomery Research Centre.

Tributes

Montgomery and her characters achieved a level of fame in her lifetime that was unprecedented in Canadian fiction. That fame only continued to grow following her death. In 1927, Montgomery received a fan letter from British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and met with the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) in Toronto.

After playing Anne in the 1934 Hollywood adaptation of Anne of Green Gables, the child star Dawn Evelyeen Paris changed her stage name from Dawn O’Day to Anne Shirley. She enjoyed a successful career under that moniker, receiving an Academy Award nomination in 1938 and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. Numerous institutions and organizations around the world are also named after Anne Shirley or Green Gables. These include The School of Green Gables, a nursing school in Okayama, Japan, and a plethora of beach houses, tea houses and other venues named Green Gables in several countries.

Anne of Green Gables enjoys its highest degree of international popularity in Poland and Japan. The book was published in seven editions in Poland between the First and Second World Wars. It was voted the country’s fourth most popular book in a 1932 poll conducted by Ruch Pedagogiczny magazine. Anne of the Island, the third book in the Anne series, was even published by the Polish Army in Palestine during the Second World War. In Japan, the novel resonated with an orphaned population following the Second World War. It has been a mandatory part of the public-school curriculum in Japan since 1952.

In 1996, the CBC TV series Life & Times aired an episode on Montgomery titled “Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Long Road to Fame.” Melanie Fishbane’s young adult novel Maud, inspired by Montgomery’s life and experiences, was published by Penguin Random House in 2017.

Honours

In 1923, Montgomery became the first Canadian woman to be made a member of the British Royal Society of Arts. In 1924, she was named one of the “Twelve Greatest Women in Canada” by the Toronto Star. In 1935, she was named to both the Order of the British Empire and the Literary and Artistic Institute of France. In 1943, she was named a Person of National Historic Significance by the Canadian government.

Canada Post issued stamps in honour of Montgomery and Anne of Green Gables in 1975 and again in 2008, in commemoration of the novel’s centennial. In 2016, the Bank of Canada included Montgomery in a list of 12 candidates to become the first Canadian woman to be featured alone on Canadian currency. (See Women on Canadian Banknotes.) In June 2024, the Royal Canadian Mint issued a commemorative $1 coin to mark 150 years since Montgomery’s birth. The coin features drawings of Montgomery and Anne Shirley by PEI artist Brenda Jones. Montgomery became the first Canadian author to be featured on a Canadian coin.

Writings

Novels

-

Anne of Green Gables Series

- Anne of Green Gables (1908)

- Anne of Avonlea (1909)

- Anne of the Island (1915)

- Anne's House of Dreams (1917)

- Rainbow Valley (1919)

- Rilla of Ingleside (1921)

- Anne of Windy Poplars (1936)

- Anne of Ingleside (1939)

- The Blythes Are Quoted (2009)

-

Emily Trilogy

- Emily of New Moon (1923)

- Emily Climbs (1925)

- Emily's Quest (1927)

-

Pat of Silver Bush Series

- Pat of Silver Bush (1933)

- Mistress Pat (1935)

-

The Story Girl Series

- The Story Girl (1911)

- The Golden Road (1913)

-

Others

- Kilmeny of the Orchard (1910)

- The Blue Castle (1926)

- Magic for Marigold (1929)

- A Tangled Web (1931)

- Jane of Lantern Hill (1937)

Short Story Collections

- Chronicles of Avonlea (1912)

- Further Chronicles of Avonlea (1920)

- The Road to Yesterday (1974)

- The Doctor's Sweetheart and Other Stories (1979)

- Akin to Anne: Tales of Other Orphans (1988)

- Along the Shore: Tales by the Sea (1989)

- Among the Shadows: Tales from the Darker Side (1990)

- After Many Days: Tales of Time Passed (1991)

- Against the Odds: Tales of Achievement (1993)

- At the Altar: Matrimonial Tales (1994)

- Across the Miles: Tales of Correspondence (1995)

- Christmas with Anne and Other Holiday Stories (1995)

Poetry

- The Watchman and Other Poems (1916)

- The Poetry of Lucy Maud Montgomery (1987)

Journals, Letters, and Essays

- The Green Gables Letters from L.M. Montgomery to Ephraim Weber, 1905–1909 (1960)

- The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career (1917; 1974)

- My Dear Mr. M: Letters to G.B. MacMillan from L.M. Montgomery (1980)

- The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery (5 vols., 1985–2004)

- The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889–1900 (2012)

- The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911 (2013)

- The L.M. Montgomery Reader, Volume 1: A Life in Print (2013)

- L.M. Montgomery's Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1911–1917 (2016)

- L.M. Montgomery's Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1918–1921 (2017)

Non-fiction

- Courageous Women (1934)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom