Minerals are naturally occurring, homogeneous geological formations. Unlike fossil fuels, such as coal, oil and natural gas, minerals are inorganic compounds, meaning they are not formed of animal or plant matter. Canada is abundant in many mineral resources — mined in every province and territory — and a world leader in the production of potash, aluminum, cobalt, diamonds, gold platinum, uranium, among others.

Regional Distribution of Mineral Resources

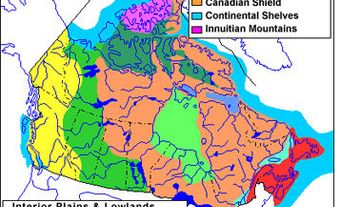

Canada covers nearly 10 million km2 and has six main geological regions, each with its own characteristic features and resources. Five of these regions and their respective mineral resources are discussed here. The sixth, Canada’s continental shelf, is a source of oil and natural gas.

Canadian Shield

The Canadian Shield is made up of Precambrian rock and underlies about half the total area of Canada. This vast expanse of ancient Precambrian igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks, glacial overburden, forest and muskeg has been Canada's leading source of precious and base metals. The area has large amounts of base metals, gold, iron ore and uranium. Because of its large size and favourable geological features, the Canadian Shield has ongoing potential for the discovery of many additional mineral deposits.

Interior Platform

Between the Canadian Shield and the Cordilleran mountain region of western Canada, and stretching from the US border to the Arctic Ocean, lies the Interior Platform, which includes the Arctic Platform, the Interior Plains, the Hudson Bay Lowlands and the St Lawrence Platform.

Under the farmland of the southern portion of the western Interior Plains are substantial mineral resources such as potash and salt, as well as oil, natural gas and coal. All of these are contained in thick sequences of gently inclined sedimentary rocks in a wedge that thickens westward towards the Rocky Mountains. In recent years, economic activity in the interior platform has been increasingly dominated by the extraction of bitumen from the oil sands.

The Hudson Bay Lowlands stretch through northern Ontario and northeastern Manitoba. They are geologically characterized by volcanic and sedimentary rocks, and contain scattered deposits of copper, zinc, gold and nickel.

The St Lawrence Platform consists of the Great Lakes Lowlands in the southwest, and the St Lawrence Lowlands in the northeast. While the region is a major producer of salt and building materials, it has been found to contain few metallic mineral resources.

Canadian Cordillera

West of the Interior Plains is the Canadian Cordillera, a mountainous region with plateaus and valleys that is underlain by various igneous and sedimentary rocks. This region covers most of British Columbia, the Yukon and the western part of the Northwest Territories, and has extensive and varied mineral resources. The western and central parts of the Cordillera contain a variety of metals — including gold, copper, iron, silver, lead and zinc — while the eastern region is noted chiefly for its deposits of fossil fuels, namely coal, oil and natural gas.

Appalachian Orogen

Southeast of the Shield, the Appalachian region of eastern Canada consists of a broad belt of mountains, hills and plains. It underlies all of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, western Newfoundland, and that part of Quebec lying south of the St Lawrence River and east of a line between Lake Champlain (US) and Quebec City. A great variety of minerals can be found there, particularly asbestos, zinc and lead. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, respectively, are home to potash and gypsum formations, and salt deposits are scattered throughout the region.

Innuitian Orogen

This region, which lies primarily in the Arctic Archipelago, is underlain mainly by folded and gently dipping sedimentary rocks. The older limestone of the Cornwallis Belt contains zinc and lead, including the rich Arvik deposit on Little Cornwallis Island, Nunavut. Other minerals, including rock salt and gypsum, have also been identified in the region but are not currently economic to mine in such a remote location.

History of Mineral Resource Development

Mining for mineral resources has played a central role in the history of Canada’s settlement and the development of its industrial economy. Today, Canada is the leading producer of potash and is estimated to rank in the top five global producers of aluminum, cobalt, diamonds, gold platinum, uranium.

18th Century

Quarrying and mining are among the oldest industries in Canada. In Quebec, for example, iron ore was mined and smelted near Trois-Rivières beginning in 1737. In 1770, Jesuit Fathers experimented with copper, found at Port Mamainse on the north shore of Lake Superior. The earliest recorded gypsum mining in Canada was by settlers in Nova Scotia in 1779.

19th Century

In the 19th century, the beginnings of an industrial economy spurred demand for durable metals. As settlers migrated to the sparsely populated regions of Upper Canada, some of the earliest extractive projects focused on iron. The first iron furnace in Ontario was erected at Furnace Falls, Leeds County, in 1800. An iron blast furnace was erected in Marmora Township, Hastings County, in 1820 and another at Normandale in 1822. The first Canadian base metal production was of copper, beginning in 1848 at Bruce Mines, Canada West (Ontario), on the north shore of Lake Huron.

In addition to iron, gold was equally influential. Extraction of the metal began in 1823, when gold concentrations were found along the shores of the Rivière Chaudière, south of Quebec City. However, this find paled in comparison to the discoveries made 35 years later in British Columbia’s Fraser River, which drew thousands of prospectors to Canada’s west coast. Mines in the Cariboo District of Central British Columbia ultimately yielded 110 tonnes of gold, and British Columbia entered Confederation in 1871 largely as a result of the rapid influx of miners during these years.

In the years following Confederation through to the 1890s, increasing exploration in southern British Columbia led to a considerable number of additional gold, silver and base-metal discoveries, including the Rossland copper-gold deposit in 1887 and the Sullivan zinc-lead deposit in 1909. Gold strikes concurrently took place on the east coast as well. Beginning in 1860, Nova Scotia’s smaller and more scattered mines yielded a total of 45 tonnes of gold.

The mineral potential of Canada became more evident with the discovery of asbestos in the Eastern Townships of Quebec (1877) and the first nickel-copper discoveries at Sudbury, Ontario, in the early 1880s. During the 1870s, Canada also emerged as a major phosphate producer, with the development of deposits of the mineral apatite in eastern Ontario and in the adjacent Gatineau Hills region of Quebec.

In 1896 gold was found in the Klondike District of what became the Yukon Territory, giving rise to one of the world's most spectacular gold rushes. From 1897 to 1899 nearly $29 million (figure unadjusted) in gold was recovered in the region. It was mined from the sands and gravels of creeks near Dawson, which for a brief period had the largest population of any community west of Winnipeg and north of Seattle. Gold production from the Yukon continues today.

Early 20th Century

Mining accelerated rapidly around the beginning of the 20th century, spurred both by the expanding demand for capital goods, as well as the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885. During the First World War, Canada's industrial capacity almost doubled. Diversification increased, transforming the steel industry from a specialized enterprise serving the railway-building market to one equipped to supply a range of products to meet the needs of an industrial economy. Following the war, the CPR and other new railroads were essential to the establishment of large-scale mining operations in the north and west, including the copper-nickel industry at Sudbury, the Britannia copper mine north of Vancouver and the Trail zinc-lead smelter in south-eastern British Columbia.

Mining projects also commenced around this time in the Prairies, but were slower in their development. The Mandy mine on the Manitoba–Saskatchewan boundary produced copper ore beginning in 1916, and a decade later the town of Flin Flon was established on the site by the Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting Company, which financed the construction of a smelter and railroad to the town.

The discovery of uranium around this time also spurred exploration of Canada’s northern geological formations. In 1930 Gilbert Labine discovered uranium-silver-radium ores at Great Bear Lake, Northwest Territories, which were mined initially for their radium and silver content, yielding by-product uranium that was used to provide yellow and orange colours in glass and ceramic glazes. In the early 1940s, with the advent of the nuclear age, uranium became the dominant metal of value in these ores, which were exhausted by 1960.

Mid-20th Century

During the Second World War, Canada became an important source of metals and of other strategic materials needed for the Allied war effort. Expansion of production was substantial in the steel and nonferrous-metal industries and in the electrical appliance, tool and chemical industries. Between 1939 and the peak period of war materials output, Canadian steel production doubled and aluminium output, based on imported bauxite and alumina, increased five-fold. During the war years, production of the base metals nickel, copper, lead and zinc increased by 50 per cent or more.

After 1945, the country quickly returned to peacetime activities. Interest in mineral resource development was renewed and new discoveries of minerals, such as iron ore, potash, copper, zinc and uranium launched Canada's mining industry into its greatest period of expansion.

The postwar era was marked by many other major mineral discoveries: deposits of nickel in Manitoba, of zinc-lead, copper and molybdenum in British Columbia, and of base metals and asbestos in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Newfoundland, the Yukon and British Columbia. In the late 1940s and early 1950s uranium was discovered in Saskatchewan and Ontario, giving Canada the world's largest known reserves of this metal in ore.

Iron ore also became important when huge deposits were mined in Quebec and Labrador. Major base-metal mines were brought into production in the Bathurst region of New Brunswick, and a smelting industry was developed there. Large deposits of potash were discovered in Saskatchewan, and North America's first tantalum mine was opened in Manitoba. The Kidd Creek zinc-copper-silver ore body, one of the world's largest, was discovered late in 1963 near Timmins, Ontario, and began production in 1965.

Late 20th Century

A resurgence in the gold price in the late 1970s resulted in a major increase in gold exploration and production in Canada.

With much higher gold prices since the late 1970s, Canada's reserves of gold in ore at Canadian mines increased more than four-fold. New gold ore bodies were discovered and new gold mines opened, including three on a major gold deposit discovered in 1981 at Hemlo, Ontario. Hemlo is one of Canada's most important gold discoveries, smaller in its gold content only than the combined Hollinger-McIntyre gold ore body in the Porcupine gold district at Timmins, Ontario, which has yielded more than 2,000 tonnes of gold.

Other important gold mines were opened from the early 1980s to 1996 in Newfoundland, northwestern Quebec, northeastern Ontario, northern Saskatchewan and British Columbia (including the extremely rich Eskay Creek gold-silver mine). Other gold mines reopened, including the former Paymaster mine at Timmins, Ontario, the former Britannia and San Antonio mines in Manitoba, and the former Nickel Plate mine in British Columbia. All of these had closed as they were no longer economic to run because of the then-fixed gold price and increasing production costs due to inflation. Nonetheless, from 1858 to 1997 Canada's cumulative production of gold totalled 8,675 tonnes, approximately seven per cent of the world's all-time cumulative gold production.

A significant portion of the world's known uranium resources are in Saskatchewan, specifically in McClean Lake, McArthur River and Cigar Lake, which were discovered in the 1980s. Saskatchewan is one of the largest uranium producing regions in the world. In 2012, the province accounted for all of Canada’s uranium production, and 22 per cent of global production.

The Voisey's Bay nickel-copper-cobalt deposit, discovered in Labrador in 1993, is one of Canada's most important nickel deposits. It is located on the eastern edge of a northern expanse of wilderness, 350 km north of Happy Valley-Goose Bay. In 1996, Vale Inco Ltd. acquired the rights to the Voisey's Bay property and began processing its first ore in August 2005.

Several diamond ore bodies have been discovered in the Northwest Territories, the first in 1992. Diamond deposits of economic significance had not previously been discovered in Canada. Canada's first diamond-mining operation began production in October 1998 at the Ekati mine in Lac de Gras, Northwest Territories, followed by the Diavik mine in 2003. According to Statistics Canada, the mines produced 13.8 million carats, worth $2.8 billion, between 1998 and 2002. Canada's third diamond mine, and Nunavut's first, was the Jericho mine, established 400 km northeast of Yellowknife by the Tahera Diamond Corporation. It was officially opened in August 2006. In 2008, De Beers began production in two mines in Canada. The Snap Lake Mine, 220 km northeast of Yellowknife, was the company's first diamond mine established outside Africa and the first Canadian diamond mine completely underground. The Victor Mine, in the James Bay Lowlands of Northern Ontario, approximately 90 km west of the Attawapiskat First Nation, is an open pit mine and Ontario's first diamond mine.

As of 2019, Canada was the third largest producer of rough diamonds globally. More importantly though, Canada's diamonds have a global reputation for being of high quality and for being "clean" in that they do not finance terror, war or weapons.

Minerals and Economic Development

Minerals have had an important impact on the social and economic development of Canada, especially in terms of the importance of mineral exports to the Canadian economy. In 2021, for example, domestic mineral exports accounted for 22 per cent of the total value of all Canadian merchandise exports. These exports were valued at $126.6 billion. From mining to marketing, the mineral industry stimulates a broad range of manufacturing and service industries.

Controversies

Mineral extraction has provoked several political conflicts in the areas of labour relations, environmental damage and Indigenous sovereignty in Canada. (See also Indigenous Peoples in Canada; Indigenous Self-Government in Canada.) Critics of the industry have consistently pointed out that although the companies themselves are often at fault for problems of poor workplace safety, pollution, ecological destruction and violations of Indigenous land claims, inadequate regulatory legislation and enforcement is often equally problematic.

Historically, labour disputes were the first major conflicts surrounding mineral extraction to capture the attention of the Canadian public. These began in particular in 1919 when miners went on strike in Cobalt and Kirkland Lake alongside thousands of other workers across the country. (See also Winnipeg General Strike.) To this day, compensation, benefits and especially job security have typically been at the heart of labour disputes, as the industry has decreased its reliance on labour through increased mechanization. In Sudbury in 2009, for example, United Steelworkers Local 6500 went on strike. The workers' grievances were against their employers' plans to restructure profit-sharing and pension agreements. In the four decades preceding the strike, the workforce had been reduced from 17,000 to 3,000 even while nickel production remained at the same levels.

Since the 1970s, increasing attention has been paid to the environmental damage caused by mining and mineral processing. The smelter at Flin Flon, for instance, had become one of Canada’s most polluting industrial facilities by the end of the 20th century, emitting massive amounts of lead, mercury and arsenic — all cancer-causing agents found in abnormally high levels in the bodies of local residents. Although mining operations continue in the area, the smelter was closed in 2010, putting over 200 people out of work.

Much of the industry’s long-term environmental damages have been caused by the chemical by-products of the extractive process, which are often concentrated in tailing ponds. These tailings, which typically contain hazardous materials such as arsenic and mercury, have on occasion been known to seep into groundwater and, in some cases, spill en masse into neighbouring watersheds. One such event occurred at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley gold and copper mine in British Columbia in August 2014, when approximately 10 billion litres of water and 4.5 million m3 of solid waste spilled into a neighbouring lake. The Mount Polley mine and another proposed project by Imperial Metals at Ruddock Creek both sit on territory that remains unceded by the Neskonlith Secwepemc First Nation. Following the disaster, the Neskonlith Band issued an eviction notice to the company, requesting that the Ruddock Creek operation be halted immediately.

Numerous other Indigenous communities throughout Canada have contested mining operations for reasons that often involve land claims as well as environmental concerns. Critics have long suggested that Canada should abandon the free entry (also known as open entry) mining laws, which allow prospecting and claim-staking on most Crown and Indigenous land. Some modifications to these laws, which exist at a provincial and territorial level, have been made, but no ruling or legislation has challenged them at the federal level.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom