The Military Service Act became law on 29 August 1917. It was a politically explosive and controversial law that bitterly divided the country along French-English lines. It made all male citizens aged 20 to 45 subject to conscription for military service, through the end of the First World War. As such, the Act had significant political consequences. It led to the creation of Prime Minister Borden’s Union Government and drove most of his French-Canadian supporters into opposition.

Reinforcements Needed

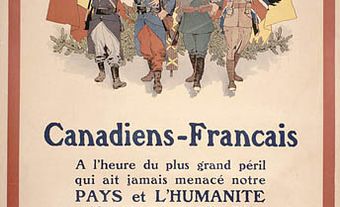

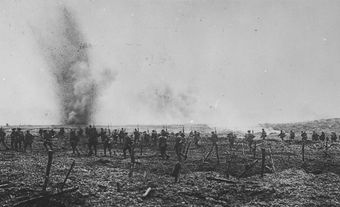

More than 300,000 Canadians signed up to fight overseas in the first two years of the First World War. This was a huge number for a country of only eight million people. By the end of 1916, however, volunteering had nearly dried up. Canada did not have enough recruits to reinforce the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The Force’s numbers were being depleted by the awful toll of the fighting in France and Belgium.

After returning from a visit to France in the spring of 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden was shocked by the enormity of the conflict. He was determined that Canada should play a significant role in the war and announced that compulsory service would be necessary.

Conscription Debate

The debate over conscription consumed and divided the country. Some French Canadians supported it and some English Canadians did not; but for the most part, English Canada backed Borden on conscription while other groups were opposed. The opponents were primarily farmers (who disliked the recruitment of their labouring sons);trade unionists; non-British immigrants; pacifists; and most of French Canada, including almost every French-speaking Member of Parliament. Riots over the issue broke out in Quebec, where support for the war had always been lukewarm.

Liberal Opposition leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier warned of a “deep cleavage amongst the Canadian people,” and refused to endorse Borden’s call for a unified, coalition government on the matter. Still, Borden managed to push the Military Service Act through Parliament; it became law on 29 August 1917. It made all male citizens aged 20 to 45 subject to call-up for military service, through the end of the war.

“If we do not pass this measure,” Borden had told Parliament, “if we do not provide reinforcements, if we do not keep our plighted faith, with what countenance shall we meet (the soldiers) on their return?”

A few weeks later, in preparation for a federal election, Borden cobbled together a Union Government. It was made up largely of English-speaking Conservatives, Liberals and independents. The election of December 1917, known as the “Khaki Election” (after the colour of the army’s uniforms), was fought on the issue of conscription. It was a bitter contest that the Unionists won; they received a large majority in the House of Commons.

The Act and Indigenous Peoples

The Military Service Act initially included Status Indians and Métis men between the ages of 20 and 45. At that time, “Status Indians” were First Nations peoples with official Indian status registered with the Department of Indian Affairs. However, some First Nations leaders challenged conscription on the grounds that it violated treaties between the Crown and Indigenous peoples; they also argued that men who did not have the right to vote should not be forced to fight in overseas wars.

As a result, Indigenous peoples (both treaty and non-treaty peoples) were exempted from the Act in January 1918. Nevertheless, some Status Indians did serve overseas as conscripts, but ultimately more than 4,000 First Nations men volunteered for overseas service between 1914 and 1918. This was in addition to the many Métis and First Nations soldiers who volunteered without identifying as Indigenous. (See also Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars.)

The Act and Black Canadians

The Military Service Act also applied to Black Canadians, many of whom faced opposition when they tried to enlist earlier in the war. (See Black Volunteers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and No. 2 Construction Battalion.) Despite this, most Black Canadians registered for military service. At least 350 were drafted into the CEF and 220 were sent overseas. The majority were assigned to the Canadian Forestry Corps, which also employed most Black volunteers. At least 28 Black conscripts served in frontline units during the Hundred Days Campaign, three of whom lost their lives. (See Black Canadians and Conscription in the First World War.)

Significance

The Military Service Act was unevenly administered. There were numerous evasions by called-up recruits, and many exemptions were granted. Thousands of young men refused to even register for the selection process. Of those that did register, 93 per cent asked for exemptions.

Call-ups began in January 1918. In total, 401,882 men registered for conscription and 124,588 were drafted to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Of those, 99,651 were taken on strength, while the rest were found unfit for service or discharged. In total, 47,509 conscripted men were sent overseas and 24,132 served in France. While these conscripts were a small portion of the 236,618 other ranks who ultimately served at the front, they did comprise a significant percentage of front line infantry in the last few months of the war; in this respect, their numbers were essential to keeping infantry battalions at full strength and provided crucial manpower to the depleted divisions of the Canadian Corps during the final costly, but successful, battles of 1918.

While conscripts were not necessary to win the war, the Canadian Corps with its four infantry divisions could not have been sustained in the field without them. Nevertheless, the Act came with a very high political cost. It led to the creation of Prime Minister Borden’s Union Government and drove most of his French-Canadian supporters into opposition. French Canadians were seriously alienated by this attempt to enforce their participation in what they considered a British imperial war. More broadly, the conscription crisis bitterly divided the country along French–English lines.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom