Canada's slaughtering and meat-processing sector comprises livestock slaughter and carcass dressing, secondary processors that manufacture and package meat products for retail sale, and purveyors that prepare portion-ready cuts for hotel, restaurant and institutional food service. Products include fresh, chilled or frozen meats and edible offal (i.e. organ meats); cured meats; fresh and cooked sausage; canned meat preparations; animal oils and fats; and products such as bone and meat meal. Meat processing is one of Canada's largest single manufacturing industries and the largest employer in the food-manufacturing group. It was among the earliest food industries to develop mass production technologies geared toward international markets.

History

Pre-industrial Meat Processing to 1870

Meat processing has always been among Canada's most regulated industries. The Superior Council of New France established regulations in 1706 to control the sale of meat in different seasons and required butchers to advise a colonial official prior to the slaughter of an animal. Inspection was required to ensure that the animal was healthy and that its meat would be fit for sale. By 1805, Lower Canada regulated beef and pork packing with legislation specifying the weight and quality of meat cuts, the quality of the barrels in which they were packed, and the amount of preservative required.

In the early 19th century, most meat originated with farm slaughter and village butchers, but meat-packing for export was becoming significant. Production scales increased as butchers sold fresh meat for domestic consumers and packed cured meat products for overseas markets. During the winter months, hogs were slaughtered, the carcasses were dressed and pork was cured and packed in barrels filled with brine. F.W. Fearman began operations in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1852 and continues to operate in nearby Burlington. Despite changes in ownership, it is Canada’s oldest pork processor. William Davies — whose company was a precursor of Canada Packers — began business in Toronto in 1854. In 1874, Davies built Canada's first large-scale hog slaughtering facility in Toronto's east end.

Industrialization of Meat-Packing, 1870–1930

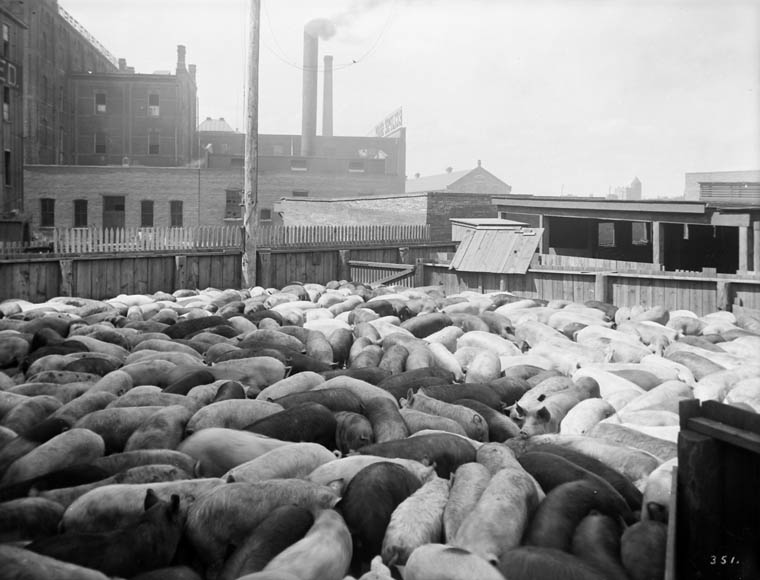

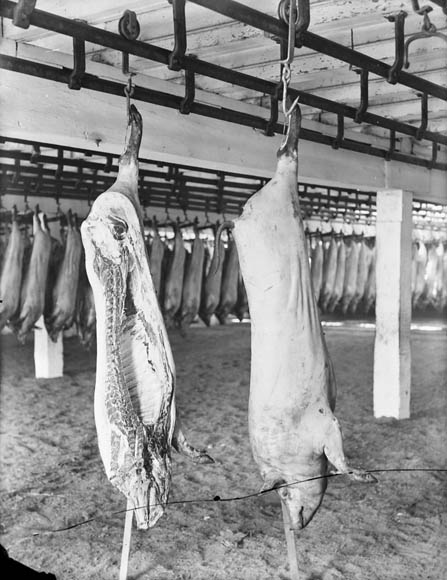

Development of industrial meat-packing in the American Midwest during the 1870s influenced meat processing in Canada. A growing railway network enabled the procurement of unprecedented volumes of livestock from a vast hinterland and the distribution of chilled meat to an extensive market aboard refrigerated railcars. The scale of production increased and packing plants came to employ a semi-skilled, largely immigrant labour force. Unlike traditional butcher shops, packing plants had a finely graduated division of labour that allowed each meat cutter to specialize in a single task as a carcass moved along an overhead rail. Inaugurated in Chicago, the industrial meat-packing model was followed in other metropolitan centres of the Midwest such as St. Louis, and at a smaller scale in Toronto and Winnipeg.

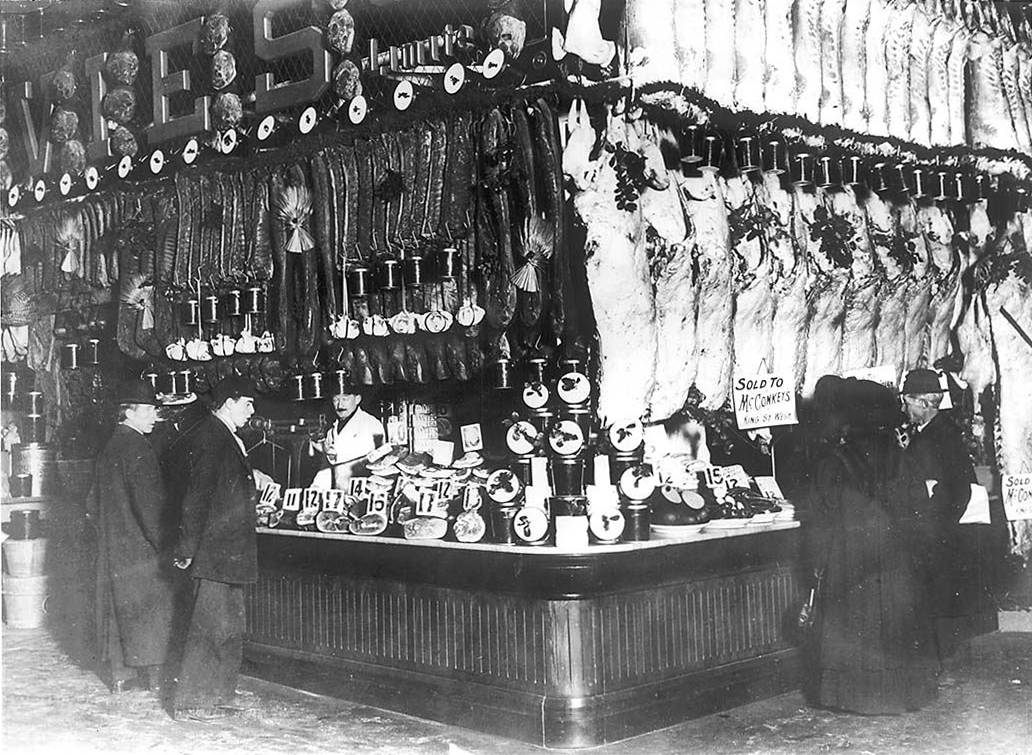

Driven by buoyant markets for cured “Wiltshire sides” of pork in Britain, the Canadian industry grew rapidly from 1880 to 1890. As meat processing industrialized, hundreds of small butcheries were absorbed by larger enterprises seeking international markets for their meat exports. By the turn of the century, meat processing establishments were among the largest employers in Canada’s food and beverage industry and sales of cured pork products became a significant part of Canada’s agro-food exports.

Patrick Burns, Alberta’s most famous “cattle king,” founded his cattle and meat-packing empire by supplying beef to railway gangs and the mining and lumber camps of Western Canada's resource periphery in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1890, he established his first substantial slaughterhouse, in Calgary. Called P. Burns & Co. (later Burns Foods), it became Western Canada's largest meat-packing company.

In the east, the Harris Abattoir was established in Toronto in 1896. With a slaughter capacity of 500 cattle per week, the Harris Abattoir was a bold innovation. It specialized in cattle slaughter at a time when most industrial meat-packers focused on pork. Unlike P. Burns & Co., it was intended primarily to export chilled sides of beef for the British market.

Influenced by calls for meat inspection in the United States — which were spurred by reactions to Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel, The Jungle, which exposed unsanitary practices at packing houses — J. G. Rutherford, veterinary director general and later livestock commissioner for Canada, was instrumental in drafting the Meat and Canned Foods Act, Canada's first federal meat inspection legislation. From 1907, federal sanitation standards required ante-mortem and post-mortem veterinary inspection of all animals whose meat was intended for export or shipment across provincial borders.

The Big Three, 1930–1980

Meat processing grew rapidly during the First World War. At that time, Sir Joseph Flavelle came to epitomize the many meat-packing industrialists who earned windfall profits through their home-front participation in the war effort. However, the industry was left with surplus capacity in the 1920s, prompting several large American meat-packers to withdraw from the Canadian market and the creation of Canada Packers — the merging of William Davies, Gunns Limited, and the Harris Abattoir.

By 1930, a new and more concentrated corporate structure emerged that would dominate the red meat industry (mainly pork and beef) for nearly 50 years. The Big Three integrated meat-packers (Canada Packers, Burns Foods, and Swift Canadian) slaughtered all species and processed their carcasses into a full line of fresh and processed meat products in packing plants from Charlottetown, PE, to Victoria, BC. Most of these plants were organized by the United Packinghouse Workers of America during the Second World War, and a system of pattern bargaining was developed that brought meat-packing wages well above the manufacturing average.

In terms of white meat, consumption began to grow substantially in the 1950s, leading to large-scale broiler processing. This shift was prompted by advances in genetics and in poultry nutrition science.

Livestock processors have relatively low profit margins, usually between one and two per cent of sales. Meat-packing profits depend on large-scale production in which the full value of animal by-products are salvaged in order to attain the sales volume required to earn an acceptable rate of return.

Meat Processing Today, 1980–present

The Big Three meat packers oligopoly restructured in the 1980s as domestic beef consumption fell and competition from American packers intensified. The Big Three withdrew from fresh beef and, through a complex series of mergers, many of their operations came under the control of Maple Leaf Foods (controlled by McCain Capital Corporation and West Face Capital Inc.), which is still the leading hog processor in Manitoba. Olymel (controlled by La Coop Fédérée) has become Québec and Alberta’s leading pork processor with nine pork and hog processing plants in Québec, one in Red Deer, Alberta, and one in Cornwall, Ontario. Beef processing is dominated by three large plants: Cargill Foods operates in High River, Alberta, and Guelph, Ontario; Lakeside Packers in Brooks, Alberta, is operated by JBS Canada, part of a Brazil-based multinational that was reputed to be the world's largest processor of fresh beef and pork in 2014.

Chicken production is distributed across all provinces in approximate proportion to the consumer market and due to Canada’s system of supply management. State-of-the-art poultry plants that slaughter and process up to 25,000 broiler chickens per hour account for the majority share of poultry meat output. Among the largest processing companies are: Lilydale Foods (Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia), Maple Leaf Poultry (Ontario and Alberta), Maple Lodge Farms (Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia), Olymel (Québec and Ontario) and Sunrise Poultry (British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Manitoba). Most poultry processors operate their own egg hatcheries that sell chicks to producers who then sell the finished birds back to the processors on a live-weight basis.

Large-scale meat processing plants increasingly specialize in just one sex, age and species of livestock and in a narrow range of meat products. However, a small but growing market segment asserts a preference for locally produced and certified organic meats that originate with livestock that are produced in less confined settings and are typically processed by small-scale, provincially-inspected plants and sold at a premium at local farmer’s markets and specialty food stores.

International Trade

From its inception in the 19th century, the meat processing industry has been a significant exporter. Led by pork and beef, meat and meat preparations are among Canada’s highest value agro-food exports. Since the US embargo on Canadian beef was lifted in 2005, those exports have accounted for about half of total production. The United States, Mexico, Japan, China, Hong Kong and Russia are the most important global importers of Canadian beef and pork, while Canadian chicken products are exported mainly to the United States and Asian destinations such as Taiwan and the Philippines.

Food Safety and Meat Inspection

Federally inspected plants account for over 90 per cent of all animals slaughtered in Canada. Since 1997, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has been responsible for verifying that the meat and poultry products leaving federally-inspected establishments are safe and wholesome. Federal inspection is required for establishments that distribute their product across provincial lines. Each province is responsible for food safety in plants that supply intra-provincial markets. Despite this relatively stringent regulatory environment, meat processors are subject to occasional episodes of contamination by pathogens such as listeria, E. coli and salmonella. Prion disease — manifest in cattle as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) — was first discovered in a Canadian-born cow in May 2003. Since that time, 17 further cases of BSE have been discovered, the most recent in February 2011. The disease may be spread by consuming brain, spinal cord, and other “specified risk materials” from infected animals. For that reason, packing house procedures are stringently regulated to ensure that such by-products do not enter the food chain for human or animal consumption.

Federally inspected red-meat processing firms are represented nationally by the Canadian Meat Council in Ottawa. The Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council speaks for the processors of chickens, turkeys and table eggs. A significant proportion of the red-meat-processing labour force is unionized and represented by the United Food and Commercial Workers.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom