The Quebec Act

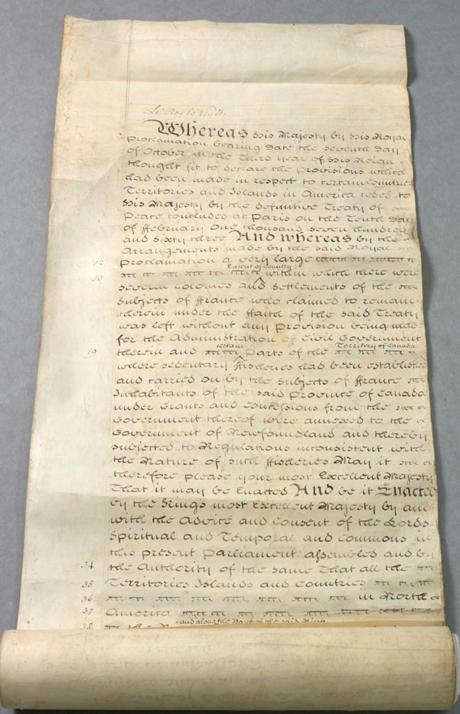

After the conquest of New France in 1760, Great Britain wanted to redraw the boundaries of its new colony. This would make room in the fisheries and the fur trade for merchants in Quebec City and Montreal. The Quebec Act of 1774 was a formal recognition of the failure of the project. The borders were adjusted to reflect the needs of a transcontinental economy.

In 1791, the fur trade still played a key role in the lives of merchants and seasonal workers in the rural population. They felt that their territory included both the St. Lawrence Valley and the huge western expanse of Rupert’s Land. In the early 19th century, however, the economic basis for this perception grew blurry. As a result, most francophone Lower Canadians came to focus on the St. Lawrence Lowlands stretching from Montreal to the Gulf of St Lawrence. When Louis-Joseph Papineau attacked the proposed union of the two Canadas in 1822, he described Lower Canada as a distinct geographic, economic and cultural space, forever destined to serve the Habitant as a Catholic and French nation.

This vision found little support among the anglophone merchants. They largely controlled the economic development of Upper Canada and continued to challenge the 1791 division. These businessmen owned the banks and means of transportation. They fervently advocated the building of canals on the St. Lawrence River. They were involved primarily in the grain trade to England and in transporting Upper Canadian forest products to the port of Quebec. They occupied an economic space that overflowed the borders of the St. Lawrence Valley. After the unsuccessful attempt to unite the two Canadas in 1822, they began calling for the annexation of Montreal to Upper Canada. This continued until after the failure of the Rebellions of 1837–38, when a single province was formed. (See also: Province of Canada.)

An Economy in Crisis

Around 1760, the colonial economy was still dominated by the fur trade and a commercial agriculture based on wheat. The fisheries, the timber trade, shipbuilding and the Forges Saint-Maurice were all secondary. The fur trade was still expanding northwards and towards the Pacific. By the end of the 18th century, 600,000 beaver pelts and other furs worth more than £400 000 were being exported annually to England.

All this activity, transcontinental and international by its very nature, was largely concentrated in the hands of the bourgeoisie, or business class, of the North West Company (NWC). (See also: Social Class.) The Montreal-based company had triumphed over its American rivals and (temporarily) over the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). However, after 1804, growing pressure from these rivals reduced profits to such an extent that the NWC was forced to merge with the HBC in 1821.

The wheat trade underwent equally important transformations. After about 1730, wheat farming (the basis for subsistence agriculture) started to become a commercial activity. This was thanks to the development of an external market. This market was mainly the Caribbean until 1760. It then expanded to include Southern Europe and Britain by the beginning of the 19th century.

Production then fell off so sharply that around 1832, Lower Canada had to import more than 500,000 minots (about 19.5 million litres) of wheat annually from Upper Canada. The deficit became chronic. Oats, potatoes and animal husbandry occasionally brought profits to some farmers. Most, however, grew these crops for subsistence. The increasing difficulties in agriculture and in the fur trade had a negative impact on the population’s standard of living.

The Timber Trade

This was the context for the rapid growth of the timber trade after 1806. (See: Timber Trade History.) Increased production and export of forest products occurred during Napoleon’s Continental Blockade. (See also: Napoleonic Wars.) To ensure it had the wood supplies needed to build warships, England introduced preferential tariffs. These were maintained at about the same level until 1840, despite successive price drops. Again, there was abundant seasonal help in Lower Canada. The forest industry, with Quebec City as its nerve centre, was especially active in the Ottawa Valley, the Eastern Townships and the Quebec and Trois-Rivières areas. Squared pine and oak, construction wood, staves, potash and shipbuilding were the industry's mainstays. (See also: Lumber and Wood Industries.)

Lower Canada’s economy was transformed by the declining price of fur and local wheat shipments. It was increasingly Quebec-centered and yet more dependent for its exports on surplus production in Upper Canada. This produced an urgent need for credit institutions and for massive investments in road and canal construction.

Overpopulation

From the early 18th century, the French Canadian population had grown without significant help from immigration. With a birthrate of about 50 births per thousand and mortality of about 25 per thousand, the population doubled every 25 to 28 years. (See also: Birthing Practices.) Following the conquest of New France, British immigration hardly affected this demographic trend, except for a limited time during the Loyalist wave. Land was so abundant and people so scarce that French Canada’s population increase continued until the end of the century.

It was in the seigneur’s interests to grant lands upon request. This gave them the largest possible number of rent payers. But early in the 19th century, this policy, combined with the high birthrate, led to the decreased accessibility of good lands. The seigneurs, prompted by the rising value of their forest products, began to limit the peasants’ access to real estate. The scarcity of land became more widespread. As a result, a rural proletariat began to develop. (See also: Social Class.) By 1830, it made up about one-third of the rural population. French Canadian emigrants to the US were largely from this group and from the impoverished peasantry. (See also: Franco-Americans.)

After 1815, the population of the rural communities along the St. Lawrence and Richelieu rivers had intensified. A massive wave of British immigrants came looking for land and jobs. Peasants and the proletariat in rural Quebec felt threatened by the strangers. They sought land in the Townships, where French Canadians had long thought their own excess population could settle. They were even more alarmed by the rapidly rising anglophone population in urban areas. In Quebec City in 1831, anglophones formed 45 per cent of the population. They comprised 50 per cent of all day-labourers. In Montreal in 1842, the percentages were 61 and 63, respectively. These factors sharpened the francophones’ feeling that their culture was in danger. This class struggle also helped strengthen the nationalist movement. (See also: Francophone Nationalism in Quebec.)

Class Struggles and Political Conflicts

The society that had developed in New France was one in which the military, nobility and clergy were dominant. The bourgeoisie, or business class, was dependent on them. (See also: Social Class.) After the British conquest in 1760, British military personnel, aristocrats and merchants replaced their francophone equivalents. But the development of class consciousness within the two bourgeoisies, the English and the French, helped set off a conflict between the middle class and the aristocrats. This arose when parliamentary institutions were introduced. The outcome in 1791 showed both the progress of the middle class and the economic and social decline of the nobility. Towards the end of the century, the power of the nobility was entirely dependent on the privileges and protection guaranteed by the heads of the colonial state.

Economic and demographic changes after 1800 led to a deterioration of social relationships. New ideologies emerged and old ones were reworked. In this context, a struggle took shape between three classes (the anglophone bourgeoisie, the French Canadian middle class and the clergy) for the leadership of society. The anglophone merchant bourgeoisie benefited the most from the 1791 reform and the recent economic expansion. They felt that their status and power were threatened by the widespread changes. These merchants wanted to build canals along the St. Lawrence River to make it navigable and to build roads into the Townships. These steps were part of a larger program that also sought to increase immigration, establish banks, and revise the state’s fiscal policies. Abolishing or reforming the seigneurial system and customary law were also on the list.

But these measures required political support from the francophone nationalists. They were on the rise and held a majority in the Legislative Assembly. Income from continued timber duties was uncertain. It depended on both the goodwill of this nationalist element and the failure of England to introduce free trade. Anglophone merchants dominated business circles in the cities. (In 1831, they made up 57 per cent and 63 per cent of the merchant class in Quebec City and Montreal, respectively.) They also played a disproportionately large role in the countryside. Nevertheless, they felt vulnerable in a colony numerically dominated by francophones.

Anglophones and Conservatism

Not surprisingly, anglophones tended to seek the political support of governors, colonial bureaucrats and even the government in London. This was because they were unable to form a majority in the legislative assembly. Thirty years of political defeats forced them to defend colonial ties to Britain and the constitutional status quo and to support conservative political ideas.

After the turn of the century, this bourgeoisie began to clash with the French-Canadian middle class, especially the professionals who were developing a national consciousness. These professionals were growing in number and aspired to form a national elite. They were keenly aware that major economic activities were increasingly controlled by anglophones. They saw this as the result of a serious injustice. As a result, they viewed the anglophone merchants and bureaucrats as enemies of the French-Canadian nation.

Their ideology was warmly welcomed among small-scale merchants in French Canada. It became more hostile to the activities on which anglophone power was based. The francophone petite bourgeoisie glorified agriculture. They defended the Coutume de Paris and the seigneurial system, which they wanted to see extended throughout the province. They also opposed the British American Land Co. and loudly insisted that Lower Canada was the exclusive property of the French Canadian nation.

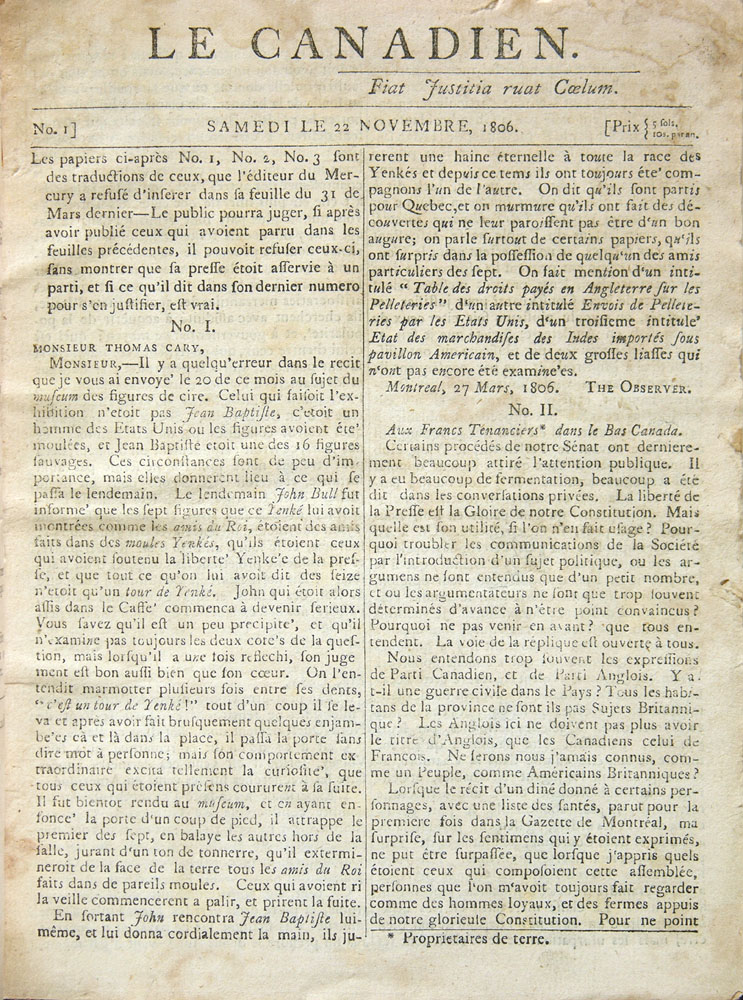

Birth of the Parti canadien

To promote its interests, the French-Canadian bourgeoisie founded the Parti canadien. (It became the Parti patriote in 1826.) Party leaders blamed economic disparities on British control of the political machine and the distribution of patronage. They therefore developed a theory that provided for political evolution along traditional British lines, but also justified rule by the majority party in the legislative assembly.

Party leader Pierre Bédard was the main architect of this strategy. It sought to apply the principle of ministerial responsibility. Its actual result was to transfer the bases of power to the francophone majority and to reduce the governor's powers. In 1810, the political climate was one of imperial wars, perpetual tension with the United States and ideas about colonial autonomy. In that context, these reformist plans seemed so radical that the suspicious Governor James Henry Craig had the editors of Le Canadien, the newspaper of the Parti canadien, arrested. After suppressing the voice of the nationalist party, he then dissolved the legislative assembly.

After the War of 1812, Louis-Joseph Papineau, the new leader of the decapitated party, felt it was most effective to seek more limited results. He focused on the struggle over control of revenues and on complaints. His immediate objective was to share power with his party’s opponents. Papineau hoped to control the clergy while winning over Irish Catholics. This would help lessen accusations of nationalist extremism. As a result, John Neilson and, later, E.B. O’Callaghan, came to hold leadership roles within the Parti canadien.

Radicalization of the Nationalists

However, after 1827, pressure from the militants and of general events caused Papineau to become more radical. The idea of an independent Lower Canada then began to take root. The desire to win power by ordinary political means was at the heart of this adjustment of political ideology. But the British model was replaced by the American model. This justified holding elections for all posts that exercised power. These included justices of the peace, militia officers, legislative councillors and even the governor.

As the political struggle intensified, the Parti patriote stirred up nationalism and gained strength among French-Canadians. However, it lost popularity among anglophones, who tended to align themselves with the anglophone merchants. Although Patriote militants agreed on the main objective — national independence — they disagreed about the kind of society that should follow their victory. The majority, which backed Papineau, wanted to continue the social ancien regime. A minority hoped to build a new society inspired by authentic liberalism. These opposing views played a major role in the failure of the rebellions of 1837–38.

Role of the Clergy

As a social class, the clergy sat atop a complex institutional network that generated great revenues. As such, they naturally became engaged in the struggle for power. Québécois clerics were already aware of the threat to their social influence. They saw this clearly in the effects of the French Revolution. It was also evident in the Protestant colonial state’s intervention in Quebec education at the turn of the century. They became even more aware when conflict flared between the Parti canadien and the merchants’ party, which was supported by the governor.

The leaders of the clergy became convinced that a local group was using parliamentary institutions to achieve revolutionary ends. Consequently, during the crisis of 1810, Monseigneur Joseph-Octave Plessis asked his priests to support the government’s candidates. But this met with little success. When the War of 1812 began, the clergy unsurprisingly denounced the Americans. They demanded, on pain of religious sanction, that the population actively defend its territory.

After 1815, clerical leaders began fighting for the restoration and even extension of their privileges. They were reassured by peace and by the more conciliatory attitude of the Parti canadien leaders. They had come to oppose the Sulpician fathers (French in origin) and now supported the clergy’s efforts to establish a diocese in Montreal.

Seeing that school was one of the main instruments of socialization, the clergy also sought to control primary education. With Papineau’s support, the clergy won a dramatic but brief victory over the Protestant and state threat when the Parish Schools Act was passed in 1824.

The clergy gained new strength when Monseigneur Jean-Jacques Lartigue became bishop of Montreal. He devoted himself to reorienting clerical ideology and strategy to better fight the threat posed by lay people and Protestants. Lartigue was well suited to the role. He was one of the first priests to break with Gallican ideology and embrace Ultramontanism and theocratic doctrine. He followed the new form of nationalism. Detached from its liberal roots, it now justified the dominant role of the clergy in a Catholic society.

Lartigue hoped to restore to the church full control over educational institutions. He wanted to bring the clergy closer to the people so as to deepen the influence of the church. But after 1829, the Parti patriote decided to establish assembly schools (nurseries for future patriotes). They also sought to democratize the management of the parishes and adopted a liberal and republican rhetoric. As a result, a break between the clergy and the French-Canadian middle class became inevitable.

Rebellions of 1837–38

The three-way power struggle became more violent in March 1837. To break the political and financial deadlock, the British government adopted the Russell Resolutions. These effectively rejected the Patriotes’ demands, which had been laid out in the 92 Resolutions of 1834. The Patriotes were not well enough organized to jump immediately into a revolutionary stance. Instead, they developed a strategy. Knowing that the state would refuse to yield to the pressure of a mass movement, they began preparing an armed insurrection. It would begin after winter set in.

The great parish and county assemblies began in 1837. Agitation spread from parish to parish. At first, only legal activities were undertaken. But these assemblies, under pressure from the radicals, soon went beyond legal limits. Government leaders saw the uproar as a massive attempt at blackmail. But the better-informed clergy immediately understood the Patriotes’ real objectives.

By July 1837, Monseigneur Lartigue had given precise instructions for his priests in the event of an armed uprising. Agitation increased until the end of October, when the Patriotes held the “Assembly of the Six Counties” in Saint-Charles-Sur-Richelieu. They issued a declaration of rights and adopted resolutions that suggested a desire to overthrow the government.

During this time, the Patriotes were very active in Montreal. They created the Fils de la Liberté, which advocated for revolution, paramilitary exercise and public demonstration. On 6 November, a violent clash between the Fils de la Liberté and the anglophone Doric Club resulted in government intervention. Such intervention was anxiously anticipated, as rural residents had been harassed by the Patriotes for some time. A few days later, the government issued arrest warrants for Patriotes leaders. They left Montreal in haste and took refuge in the countryside.

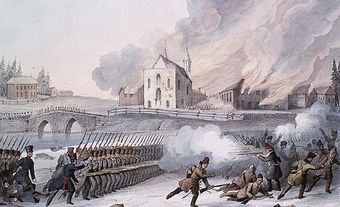

Defeat of the Patriotes and the Role of Lord Durham

Armed confrontation came well ahead of the Patriotes’ intended timetable. Following an incident in Longueuil on 16 November, the government sent troops into the Richelieu Valley. On 23 November 1837, the Patriotes, led by Wolfred Nelson, took Saint-Denis. (See also: Battle of St-Denis.) However, two days later, they were defeated at Saint-Charles. (See also: Battle of St-Charles.) The last insurgent ranks were scattered south of Montreal. General John Colborne then attacked Saint-Eustache on 14 December and ended the Patriote resistance. (See also: Battle of St-Eustache.)

Papineau had hidden in Saint-Hyacinthe. He then took refuge in the US under an assumed name. Many refugees gathered in the US and attempted to plan an invasion of Lower Canada. Their efforts were complicated by a rift between Patriote radicals, such as Cyrille Coté and Robert Nelson, and the more conservative elements led by Papineau. Ultimately, Lord Durham, as Governor General and High Commissioner to British North America, was sent to calm tempers.

In 1837, Durham banished some of the more radical political prisoners. But he was reprimanded by the government in London, which reversed his decision. Durham believed that it was necessary to unify Canada and assimilate the French Canadians. Durham resigned his post and left Canada in early November 1838. A second rebellion then broke out, led by the radicals. (See also: Rebellion in Lower Canada.) Through the efforts of the Association des frères chasseurs, the revolutionary organization had spread throughout the territory. (See also: Hunters’ Lodges.) The Patriotes had no more luck than the year before. By about mid-November 1838, order had been re-established in the Richelieu Valley.

In 1838, 850 suspects were arrested; 108 were brought before a court-martial and 99 were sentenced to death. Only a dozen were hanged and 58 were deported to Australia. The main winners in the revolution were the clergy, with its special vision of a French Catholic nation. The anglophone bourgeoisie, with its plans for development through economic measures, also came out on top. In 1840, the British parliament followed the main recommendation of the Durham Report and passed the Act of Union. It led to the unification of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada in 1841.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom