First Celebrations and American Influence

Before the 1880s, people held sporadic festivities in connection with larger labour movements. Some historians trace the origin of Labour Day to the Nine Hour Movement (1872).

Labour organizations began to hold celebrations more frequently following a labour convention in New York in September 1882. Spurred on by this initial success, the American Federation of Labor and the Knights of Labor actively promoted workers’ celebrations on the first Monday in September in the United States. The Canadian chapters of these organizations did the same. Records show similar gatherings in Toronto (1882); Hamilton and Oshawa (1883); Montreal (1886); St. Catharines (1887); Halifax (1888); Ottawa and Vancouver (1890); and London (1892).

Statutory Holiday

As the event grew more popular nationwide, labour organizations pressured governments to declare the first Monday in September a statutory holiday (see National Holidays). Their impact was significant enough that the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada (1886–89) recommended that the federal government establish a “labour day.” Before this, the day had official status in only a few municipalities. Montreal, for example, declared it a civic holiday in 1889.

In March and April 1894, more than 50 labour organizations from Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Manitoba and British Columbia petitioned parliamentarians. These groups included several regional trade and labour councils, as well as local assemblies of the Knights of Labor. They based their lobbying movement on similar initiatives from American unions. In the House of Commons, a bill sponsored by Prime Minister John Thompson prompted the debate about the holiday’s legal status in May 1894. The House passed an amended holiday law without major discussion. It received royal assent on 23 July. The United States federal government also recognized the holiday in 1894.

The provinces had no choice but to adapt. For example, Quebec parliamentarians announced that the province’s courts would not sit on the first Monday in September of that year. It wasn’t until 1899 that the province granted the holiday legal status, ordering school boards to delay the start of classes until after the first Monday in September.

Parades and Popular Celebrations

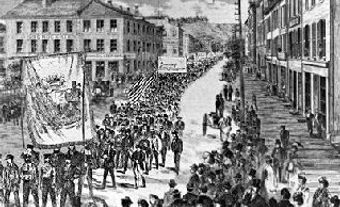

Canadians celebrated Labour Day with much ceremony on 3 September 1894. In Montreal, the city’s Trades and Labour Congress played a key role in organizing events for the day. A parade set out from the Champ de Mars park at 9:00 a.m. Its divisions grouped together unions representing the same trade. The Grande-Hermine local assembly of the Knights of Labor led the way. It guided participants to a park where they held speeches, games and a picnic. In Quebec City, the Trades and Labour Congress chose instead to hold a mass followed by entertainment. This included bicycle competitions, foot races and a lacrosse match.

Until the early 1950s, labour organizations held similar Labour Day celebrations throughout Canada. They tread a fine line between politics and pleasure, maintaining the tradition of the Victorian-era holidays. The event served as a forum for unions to voice their demands. But it also helped build working-class identity and allowed time for rest and socializing outside the workplace.

The image of the tradesman and the male breadwinner was front and centre in the festivities. Although working women attended and helped organize events by preparing food for participants, they rarely featured in the parade. The military-style marching was at odds with the image of respectability imposed upon women at the time. But for a few exceptions, their role was limited to waving at the crowd from floats as wives or ancillary workers (see Women in the Labour Force). The absence of unskilled and non-unionized workers also limited the participation of immigrant workers, members of racialized communities and Indigenous people.

The parade was the main event. Depending on the city, it could attract thousands of participants and spectators. It became more elaborate over time. Drawing inspiration from other popular parades, organizers added floats and marching bands. In Quebec, the holiday had a strong religious connotation. This grew with the development of Catholic unionism. Particularly influential in Quebec was the 1921 creation of the Catholic Workers Confederation of Canada. In 1960, it became the Confederation of National Trade Unions.

Decline of Labour Day

In the 1950s, Labour Day festivities began to draw fewer and fewer participants. In Montreal, organizers tried for a time to replace the parade with a performance and ceremonies. They saw little success, however. There were several reasons for this decline. According to historian Jacques Rouillard, the emergence of a leisure and consumer society meant that people were more likely to leave town or relax with family than attend a parade. Participation decreased further due to changes in the world of trade unions. Craft unions had traditionally organized Labour Day events. But the rise of industrial unionism, representing unskilled and semi-skilled workers, changed the day’s impact and meaning. Not everyone identified with the traditional “pride in the trade” message repeated during the celebrations. Furthermore, the Cold War divided organized labour into various rival factions. This made organizing festivities more difficult.

Competing events also took participants away from Labour Day festivities. Socialists, communists and Marxists celebrated May Day, or International Workers’ Day (1 May). Over time, this holiday acquired a more militant character than Labour Day. Many unions chose to hold their parade on that day instead. Similarly, in the mid-1970s, International Women’s Day (8 March) became an alternative celebration for feminist unionism.

Formal Labour Day celebrations nevertheless continue today alongside informal celebrations. For example, parades are still held in Toronto and Ottawa on the first Monday in September.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom