Origins and Expansion

The Knights of Labor was founded in 1869, in Philadelphia, by a group of garment cutters. This secret society expanded throughout the 1870s, aiming to organize all workers regardless of qualifications, gender or race. Its local assemblies began spreading throughout the United States, thanks to the economic climate and the disorganized state of craft unions. Its greatest success was in organizing men and women from various trades. The Knights eventually adopted an official structure and a constitution in 1878, and the following year, trade unionist Terence V. Powderly was named head of the organization, a position he held until 1893.

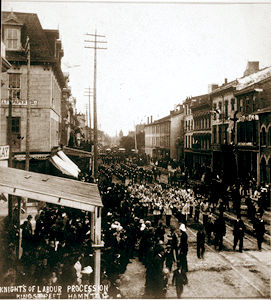

The Knights grew considerably between 1881 and 1886, gaining more than 700,000 North American members. During this time, it took root in Canada, first in Ontario (specifically in Hamilton) in 1881, and in Québec in 1882, when the Knights established the Dominion Assembly in Montréal. Its members also went on to found the Francophone-only Ville-Marie Assembly in 1884.

Knights had a particularly strong presence in Ontario, Québec and British Columbia, it also found success in Nova Scotia and Manitoba, and established local assemblies in New Brunswick and present-day Alberta. Although records remain incomplete, the Knights had an estimated 12,000 to 14,000 Canadian members between 1886 and 1888.

As the organization expanded, the Knights began to butt heads with the Catholic clergy in Québec, which branded it as a forbidden society in 1884 and threatened its members with excommunication. In Québec City, Mgr Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereaulashed out at the Knights and had the Vatican ban the organization from the province in 1884. It took intense lobbying from Canadian and American bishops to lift the ban in April 1887, an event which coincided with a with an increase in membership.

Principles and Ideology

Contrary to craft unions, which aimed to provide their members with immediate economic benefits, the Knights of Labor pursued an extensive reform agenda. Its union practices were based on cooperation, arbitration, education and political action, ideas that could be found in its Declaration of Principles, which advocated for several measures including eight-hour work days, improved hygiene and safety conditions in the workplace, equal pay for men and women, and nationalization of telegraph, telephone and public transport services.

The Knights also held a dualistic view of society, separating the working class from those who were idle or capitalist. This vision explains why there were not only labourers among its members, but also merchants, professionals and small business owners. The Knights ultimately aimed for harmony among these classes. This ideology, combined with a distinct organizational culture (including initiation rituals, social assistance and political debates), created a unique identity among the members of Knights.

Struggles and Political Action

The Knights of Labor did not have a reputation for going on strike. Its leaders favoured arbitration, and considered striking a last resort. The Knights had no strike fund and left the financial burden of such conflicts up to regional assemblies. It used arbitration to resolve 27 labour disputes between 1886 and 1893 in Montréal.

The organization also found success in institutionalizing the labour movement. Its leaders played a key role in the creation of the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada (TLC) in 1883 and of central regional councils, which became centres for mediation between union members and for discussion forums about political action.

During the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital (1886–1889), members of the Knights increased their representation, notably in Ottawa, where they created a legislative committee designed to lobby politicians in the capital.

During elections, the Knights supported a number of independent labour candidates, such as typesetter Alphonse-Télesphore Lépine, who was elected to the House of Commons in 1888. During his mandate (1888–1896), Lépine introduced a bill regarding the eight-hour work day and increased pressure to appoint members of the Knights to positions within the public service. Other influential members such as Alexander Whytes Wright, Thomas Phillips Thompson and Daniel John O’Donoghue ran for office or found careers within the public service.

The Knights had a special focus on education for the working masses. Through the creation of labour newspapers such as L’Union ouvrière nationale, Le Trait d’union and the Canadian Workingman in Montréal, the Canadian Labor Reformer in Toronto and the Palladium of Labor in Hamilton, leaders hoped to increase working-class consciousness. The Knights also hosted talks, funded public libraries, and offered night classes.

Decline

The Knights’ decline can be explained by several factors. Eventually, the American movement could no longer manage its level of growth. In Canada, the movement was not uniform. While numbers in Ontario were drying up at the end of the 1880s, they remained particularly high in Québec. In 1901, more than half of the remaining 24 assembles were located in Montréal and Québec City.

The Knights also fell victim to the successes of the American Federation of Labor, which aimed to federate craft unions. The struggle between the two unions was fierce in Montréal when a schism occurred within the TLC. The struggle pushed the Canadian Knights to reclaim its autonomy and compete with the American Federation on nationalist foundations. Finally, the TLC conference in Berlin (Kitchener) in 1902 saw the Knights expelled from the organization. However, the Knights’ nationalist views left their mark and would later lead to a rise in French-Canadian and Québécois trade unionism.

See also Working-Class History; Working Class History – Québec.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom