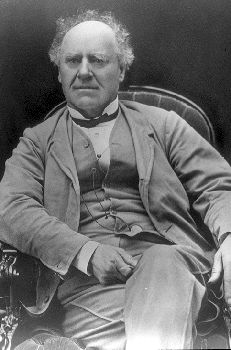

Joseph Howe, journalist, publisher, politician, premier of Nova Scotia, lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia (born 13 December 1804 in Halifax, NS; died 1 June 1873 in Halifax, NS). Howe was well-known in his time as an ardent defender of freedom of the press and freedom of speech, and was also a champion of responsible government. He was a prominent figure in the movement opposed to Confederation, yet later, as a federal Cabinet minister, played an important role in securing Manitoba’s entry to Confederation.

Early Life and Education

Joseph Howe was born to Loyalist parents, John Howe and Mary Edes Austen, in the Northwest Arm area of what is today the Halifax Regional Municipality. Howe was particularly close with his father, who he is reported to have described as “my only instructor, my play-fellow, almost my daily companion.” Howe was largely self-taught and a voracious reader, though he grew up in relatively poor circumstances and therefore could not afford many books. He was described as a keen observer of the world around him, from which he gleaned part of his knowledge. By age 13, he was assisting his father as postmaster general and King’s printer, though because he was not the eldest son, these responsibilities would not be transferred to him as an adult.

Howe’s father was said to have been the only Loyalist in his family. His love of Britain and the British Empire was conveyed to his son at a very young age and was further enforced and strengthened throughout his life. Despite Howe’s efforts to secure responsible government (i.e., elected legislative government responsible to the local electorate), he was nonetheless a committed champion of the British Empire. (See Imperialism.)

Publishing Career

Howe began his career in publishing in early 1827, when he and a partner purchased a newspaper called the Weekly Chronicle, which they then rechristened as the Acadian. Within the year, Howe took over the publication and became the editor of the Novascotian, which rapidly became the dominant newspaper in the province.

Joseph Howe married Catherine Susan Ann McNab in 1828 and they had ten children together, five of whom survived into adulthood. During his editorship of the Novascotian, Howe regularly reported on the proceedings of the legislature, described his travels throughout the province and discussed what he had learned from the newspapers, journals, pamphlets, correspondence and other periodicals that arrived on his desk. He also published original Nova Scotian literature and regularly included his own poetry.

Libel Trial

On 1 January 1835, an anonymous letter was published in the Novascotian that alleged local magistrates and police had pocketed £30,000 over three decades from local citizens (essentially through various forms of extortion). Though Howe had not written the letter (and it was signed by “The People”), he had embarked on a campaign to draw attention to local corruption throughout the previous year, which had annoyed the local political elites. As the publisher and editor of the newspaper, he was charged with seditious libel, a very serious charge at the time. Moreover, Howe couldn’t defend himself by simply arguing what had been reported was the truth, as this was not considered an adequate defence at the time. When no lawyer offered to defend Howe, he chose to defend himself, believing that he could persuade a jury to acquit him.

It was during his defence that Howe demonstrated the oratorical skills that would make him famous, and eventually lead him into the political arena. Despite the judge instructing the jury to find Howe guilty, Howe had convinced the jury instead to acquit him, a decision they arrived at in no more than 10 minutes. Upon his acquittal, he proclaimed “the press of Nova Scotia is Free.” Throughout his defence, Howe listed examples of fraud, incompetence and corruption on the part of local politicians, magistrates, police and other officials. Some of those he named resigned in the wake of his monumental acquittal. He would be elected for the first time the following year.

Responsible Government

Joseph Howe was first elected to represent Halifax in the Nova Scotia legislature (House of Assembly) in 1836. He joined the executive council in 1840 and remained in that position until 1843, the year he resigned. During this time, he campaigned for responsible government. The development of responsible government in Canada in the first half of the 19th century paved the way for Confederation in 1867. Thanks to Howe’s efforts, the assemblies elected in 1836 and 1840 had a majority of Reform (pro-responsible government) candidates. This irritated the established political elites, and Howe was challenged to a duel in 1840 by John Halliburton, son of Chief Justice Brenton Halliburton who presided over Howe’s libel trial. Halliburton missed his shot and Howe fired his gun into the air.

Howe took up the role of speaker of the Assembly in 1841, and in the same year, sold the Novascotian, having decided to focus his efforts entirely on politics. He returned to editing both the Novascotian and the Weekly Chronicle from 1844–46. Howe was highly critical of Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor, Lord Falkland, and this ultimately led to Falkland’s resignation in 1846, which, in turn, allowed for responsible government to take hold in the colony. Though Howe was a major proponent of responsible government, he was not rewarded for the accomplishment, owing at least in part to his very public and antagonistic criticism of those who stood in the way of political reform. As responsible government took hold, Howe worked as provincial secretary to integrate the province’s institutions into the new form of government.

Railways

In the early 1850s, Joseph Howe was preoccupied with plans to develop new railways, both in Nova Scotia and to connect Halifax with major nearby ports, including Quebec City and Portland, Maine. It took several attempts to secure funding for his railway plan, and in 1854, he resigned his position as provincial secretary to lead a bipartisan railway board. Though his dream was a Quebec City to Halifax line, under his leadership, lines were built only from Halifax to Windsor and Truro, Nova Scotia. Howe viewed railway development as part of a larger master plan for the development of the British Empire, a scheme which involved developing railways to open British North America for the settlement of Britain’s poorest citizens.

In 1855, he took up the cause of recruiting for the British Army and Royal Navy, then embroiled in the Crimean War. This mission brought him into the United States in search of volunteers and further drew him into conflict with Nova Scotia’s resident Irish population, who opposed the war. Howe’s effort ultimately caused a rift with Catholic voters that toppled the Reform government in 1857.

Premier of Nova Scotia

Howe served as premier of Nova Scotia from 1861–63, though his administration was hampered by an insecure majority and the constant attack by his long-time Conservative political rival (and future prime minister), Sir Charles Tupper. Howe accepted the role of leader of the Liberal Party when elected premier William Young was appointed a judge. Howe accepted the invitation to become the Imperial Fisheries Commissioner in 1863, a role he kept until 1866. He contested the 1863 election, but the Liberal Party was soundly defeated, therefore ending his role as premier.

Opposition to Confederation

From 1866–69, Howe was the leader of anti-Confederation forces in Nova Scotia, and was a prominent voice opposed to Confederation. Howe opposed Confederation in part because he believed the process lacked the involvement of the population at large, and also because it conflicted with his ideal vision for the future of the British Empire (namely that colonial populations would have rights on an equal level with the resident populations of Great Britain). Additionally, Howe was concerned that Confederation would lead to economic ruin for Nova Scotia and a loss of its independence, both of which would appear to come true in the years immediately following 1867.

Howe led a delegation to England in 1866 and 1867 to oppose Confederation. Though he participated in the first dominion parliament, Howe spent February through July of 1868 in England, leading a delegation advocating for the repeal of Confederation. Howe ultimately succeeded in getting a single concession — a review of fishing, trade and taxation policies and their effects on Nova Scotia — but British disinterest in North American affairs left Howe severely disillusioned with the empire he once held in highest esteem.

Post-Confederation Politics and Death

Howe abandoned his efforts to repeal Confederation, and rededicated himself to the government of the new dominion. In early 1869, he and a fellow MP reached an agreement with the federal finance minister to secure an improved economic position for the province. By the end of January, he ascended to a Cabinet position as president of the Privy Council. He fought and won a by-election that winter, though it left him in chronic ill health afterwards. In November of 1869, he became secretary of state for the provinces and played a role in welcoming Manitoba into Confederation. (See Manitoba and Confederation.) He was also appointed Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs in December. In May 1873, he became Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor, though died in office just three weeks later.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom