John Murray Gibbon, railway publicist and author (born 12 April 1875 in Udeweller, Ceylon [Sri Lanka]; died 2 July 1952 in Montreal, QC). A publicist with the Canadian Pacific Railway, Gibbon also actively promoted Canadian arts and culture. He organized cultural festivals, organizations that promoted tourism in the Rockies and founded the Canadian Authors Association. Gibbon also authored several articles, poems and novels. His book Canadian Mosaic (1938) popularized the "mosaic" as a metaphor for the diversity of "the Canadian people.” It has since been used by politicians, educators and policy makers to describe the cultural makeup of the country.

Early Life and Education

John Murray Gibbon was the sixth child of an eventual eight born to William Duff Gibbon (1837–1919) and Katharine G. Gibbon (née Murray, 1842–1916). William Gibbon was a Scottish emigrant to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he worked in the tea industry. When John Gibbon was four, he and his siblings were sent to live with a Protestant minister’s family in Aberdeen, Scotland, where they were to be educated.

He was a bright student, going on to finish in the top of many of his classes at Robert Gordon’s College and winning a bursary from King’s College at the University of Aberdeen, where he went on to study from 1891–94. He skipped his final year at the college, instead taking a scholarship at Oxford, where he earned a BA in Classics at Christ Church.

Upon graduation in 1898, he considered joining the British Home Service or the Indian Civil Service but instead took an unpaid apprenticeship at Black and White, an illustrated weekly paper in London. He then became editor of a spin-off publication entitled Black and White Budget and, now earning a salary, married his long-time girlfriend, Anne Fox. He subsequently worked as a freelance journalist before accepting a position as publicist with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1907. Gibbon worked in the London office until 1913, when he moved to the Montreal offices with the title of General Publicity Agent.

By 1914, he had a home constructed in Ste Anne de Bellevue and sent for his wife and their three children, Murray, Ann Faith and John (their fourth child, Philip, would be born later that year).

Promoting Canadian Arts and Culture

When John Murray Gibbon went to work publicizing the CPR in Canada, he turned to his interest in folk cultures. He organized a series of cultural festivals between 1927 and 1931, many of which featured folksongs and handicraft displays. Elected to the Royal Society of Canada in 1922, his research for that venue focused primarily on folk music. Throughout this period, he translated and published several collections of French folksongs, and he later served as president of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild (1942–44).

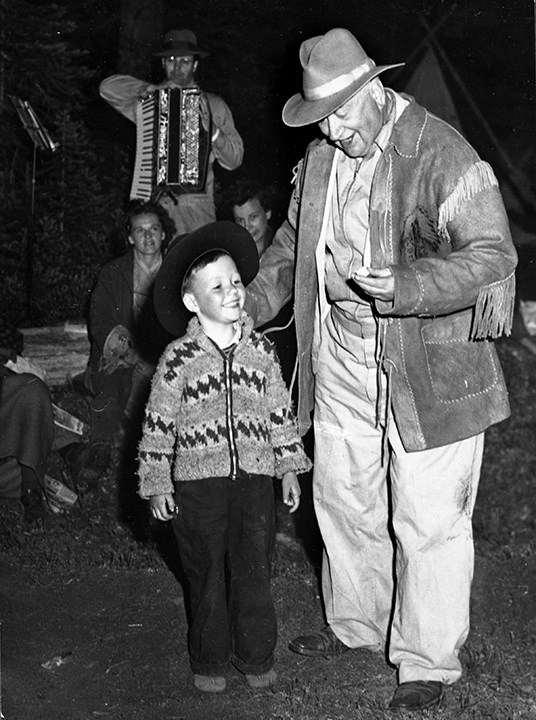

Another combination of his personal and professional interests was the creation of two organizations that promoted tourism in the Rockies: Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies (1923) and Skyline Hikers of the Canadian Rockies (1933). An alpine pass that he reportedly discovered still bears his name and is marked with a large cairn.

Gibbon’s wide authorship included articles, poems, numerous works of nonfiction and five novels. His life-long interest in the relationship between poetry and music resulted in several articles and a book-length study, Melody and the Lyric (1930), which was awarded the David Prize. He also authored a history of the CPR, published in 1935 as Steel of Empire. With B.K. Sandwell, Pelham Edgar and Stephen Leacock, he founded the Canadian Authors Association, serving as its first president (1921–22; he would be named honorary president in 1943).

Promoting Pluralism

From his first trip to the region, John Murray Gibbon was fascinated with the diversity of western Canada, later writing that “the prairies were Europe transplanted.” At the time, immigration was a subject of heated debate, so Gibbon worked to promote tolerance. He first employed the metaphor of a garden: immigrants were European seeds being planted in Canadian soil, where, if they were properly tended, they would bloom and their folk cultures, like colorful flowers, would be a welcome addition to Canadian society. (See also Immigration to Canada.)

Gibbon later developed the metaphor of the mosaic. First employed in a CBC radio series entitled “Canadian Mosaic: Songs of Many Races,” it was fully popularized when Gibbon expanded the script into a book. Published in 1938 as Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation, the book set out to examine the cultural background of the various groups that had immigrated to Canada. It explained that each immigrant’s culture represented a colourful tile that was cemented into place through the work of integrating agencies (to whom the book was dedicated), such as the YMCA and YWCA, the IODE, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, the Council of Friendship and various religious organizations. The immensely popular book was awarded the Governor General’s Award for nonfiction.

Like the folk festivals that came before it, the Canadian Mosaic did not include the cultures of people of African or Asian descent but instead exclusively discussed European groups. It also omitted discussion of Indigenous cultures, arguing “the Canadian race of the future is being superimposed on the original native Indian races.”

Legacy and Significance

John Murray Gibbon received an honorary doctorate from l’Université de Montréal and was awarded the Lorne Pierce Gold Medal from the Royal Society of Canada. He received an honorary chieftainship in the Stoney (Nakoda) nation, likely due to his role in promoting trail riding in the Rockies, a tourist-oriented business which employed many Nakoda guides. Gibbon was also lauded as a “nation builder” in a special ceremony organized by the Composers, Authors, and Publishers Association of Canada. Three years after his death, Gibbon was recognized as a Person of National Historical Significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. He was commemorated with a bronze plaque affixed to a granite monument, located on the grounds of the Banff School of Fine Arts. (See also National Historic Sites in Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom