Early Life

Simcoe was the son of Captain John Simcoe and Katherine Stamford. Captain Simcoe, commander of the British warship HMS Pembroke, was part of the British military expedition to Québec in 1759 that led to the conquest of New France. He died from pneumonia near Anticosti Island in May, prior to the actual conflict. John Graves Simcoe was seven years old at the time.

After the death of her husband, Katherine Simcoe returned to Exeter where her son John was then educated. Completing terms at Eton College and Merton College, Oxford, Simcoe opted to pursue a military career. In 1770, he attained a commission as ensign in the 35th Regiment of Foot.

American Revolutionary War

Simcoe arrived in America two days after the Battle of Bunker Hill, and sought unsuccessfully to raise a corps of free Black troops. During the subsequent siege of Boston, he purchased a captaincy in the 40th Regiment of Foot. With this regiment, he participated in campaigns in Long Island, New York City, New Jersey and Brandywine, Pennsylvania, where he was wounded.

Simcoe developed an appreciation for light infantry, particularly in the American theatre, based on the concept of individual fitness, quick movement and battlefield discipline. In October 1777 he took command of the Queen’s Rangers with the provincial rank of major. The Rangers were active in campaigns in Pennyslvania, Richmond and Yorktown. Simcoe achieved great personal success and a reputation as a tactical theorist. Prior to the British surrender at Yorktown, he was invalided home in 1781 with a rank of lieutenant-colonel.

Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada

While convalescing in England, Simcoe met Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim. They married on 30 December 1782. After a brief term in the British Parliament, Simcoe received a commission on 12 September 1791 to become the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. Simcoe hoped for an independent governorship, and was disappointed when he was made subordinate to Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester, who was commissioned governor-in-chief of both Upper and Lower Canada on the same date.

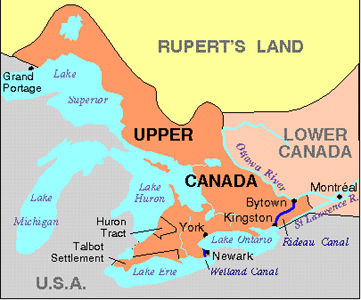

Simcoe arrived in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1792. Given the possibility of renewed hostilities between Britain and the United States, Simcoe determined that Newark, situated on the Upper Canadian–US border, was a strategically poor choice for a provincial capital. He temporarily moved the capital to York on the north shore of Lake Ontario. His preferred site – London in the southwestern part of the colony – did not receive the support of Guy Carleton. So York, current-day Toronto, became the permanent seat of government.

Achievements

Simcoe had some legislative triumphs and many more administrative frustrations. He succeeded in his first legislative session to pass bills establishing British civil law, trial by jury, the use of British Winchester standards of measure, and a provision for jails and courthouses.

Most notably, Simcoe passed the Act Against Slavery on 9 July 1793, aimed at ending the sale of slaves by Canadians to Americans. The act also liberated slaves entering Upper Canada from the US, but did not free existing adult slaves already in residence. The legislation came 40 years before the Slavery Abolition Act, which later outlawed slavery in most of the British Empire.

Simcoe was a staunch supporter of British institutions, although he admired American entrepreneurship, particularly in agriculture and settlement. He began the policy of granting land to American settlers, confident that they would become loyal members of the colony, and aware that they were the main hope for rapid economic growth. He thought their loyalty could be attained starting with a solid land-granting system. It soon proved that Simcoe was an avid planner but poor administrator. He granted entire townships to individuals who would serve as local gentry. The majority of his grants were more than 500 acres, with the best locations going to officers of government.

Two significant roads constructed during Simcoe’s term were designed for military purposes, and to influence the direction of future settlements. Dundas Street ran from Burlington Bay to his chosen site for London. Yonge Street ran north to Holland Landing.

Failed Policies

Simcoe proposed a re-establishment of the Queen’s Rangers regiment, but of the 12 companies he sought, only two infantry companies came to fruition. To Simcoe’s dismay, Carleton retained command over their deployment. The Rangers' fate became that of road builders.

Other initiatives for the economic and social growth of the colony had disappointing results. Simcoe wanted to attract the trade of the western American settlements. He saw the southwestern peninsula of Upper Canada as the future centre not only of the province, but of trade with the interior of the continent.

As part of his desire to make the province an example of the superiority of British institutions, he appointed lieutenants of counties, and introduced a Court of King's Bench. He proposed municipal councils, and urged the creation of a university with preparatory schools.

Simcoe had few critics in the province, but could not persuade the imperial government in Britain to finance his projects or to exempt him from the military authority of Guy Carleton, based in Québec.

In 1796, neuralgia and gout spurred a leave of absence to England. Simcoe resigned his post in 1798, and did not return to Canada.

Saint-Domingue and Death

Simcoe remained active in the military. In 1797, he commanded British forces in Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti). The appointment included a promotion to lieutenant-general. In Haiti, Simcoe faced a slave revolt with French Republican and Spanish support. He resigned after five months due to ill health. Although faced with an unwinnable situation, Simcoe nonetheless bore the stigma for the mission’s failure.

Back in England, Simcoe accepted command of the Western District but did not receive another active field command during the tenure of British prime minister William Pitt. In 1806, after Pitt’s death, Simcoe was appointed commander-in-chief of India. However, he died in Exeter prior to assuming the post and was buried on the family estate near Honiton.

Legacy

Simcoe’s Canadian legacy is ever present in modern-day Ontario. The town of Simcoe bears his name as does Simcoe County. The August civic holiday is known in Toronto as Simcoe Day. Schools and streets throughout Ontario are named after him, including John and Simcoe streets in Toronto. A statue was erected in his honour in 1903 at Queen’s Park.

However, Lake Simcoe is not named for Simcoe. He, in fact, named it after his father, Captain John Simcoe.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom