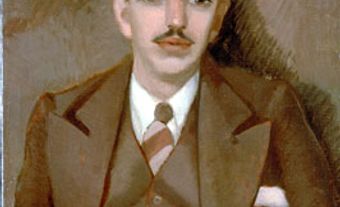

Jean Paul Riopelle, CC, GOQ, painter (born 7 October 1923 in Montréal, QC; died 12 March 2002 in Isle-aux-Grues, QC). Jean Paul Riopelle was one of the most important artists of the 20th century and one of the first Canadian artists to gain major international recognition. He was one of the original signatories, along with Paul-Émile Borduas, of the Refus Global. Riopelle represented Canada at the 1962 Venice Biennale, where he won the UNESCO Award. His technique of painting with a palette knife gave his work a sculptural quality. His work is featured in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, among others. He was made a Companion of the Order of Canada and a Grand officier of the Ordre national du Québec.

Early Life and Education

The son of a builder who liked to be called “bourgeois,” Jean Paul Riopelle began taking drawing lessons with Henri Bisson when he was about 13. Bisson was his French and mathematics teacher at the school Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague in Montreal and gave painting lessons on weekends. His motto was “to copy nature.” Riopelle’s Nature bien morte (1942) is a copy of one of the Bisson’s paintings. Hibou premier (1939) was inspired by a stuffed animal in Bisson’s hunting collection.

Riopelle’s parents, however, dreamed of a different career for their son, not that of a painter. They wanted him to follow in his father’s footsteps, to go beyond even, and become an architect. In 1941 and 1942, Riopelle studied at the École Polytechnique in Montreal but without success. He finally ended up at the École du meuble in 1942.

The painter Paul-Émile Borduas was teaching at the École du meuble and had Riopelle as a student. Riopelle rebelled against Borduas at first because Borduas didn’t appreciate his ability to make “realistic” paintings in the manner he had learned from Bisson. Riopelle later said that he was the “provocateur” in Borduas’s classes. But he slowly opened himself to a freer, more spontaneous style of painting.

The Birth of Automatism

Jean Paul Riopelle began experimenting with Marcel Barbeau, Jean-Paul Mousseau and Bernard Morisset in a makeshift studio (a shed that Barbeau rented) behind a house on rue Saint-Hubert in Montreal. Here, Riopelle produced what could be described as his first automatist paintings. Painted with commercial house paint on jute for lack of money, little of this work has survived.

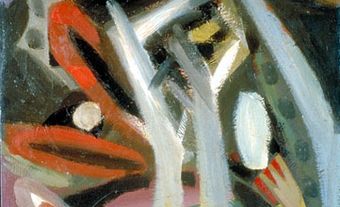

By 1947, Riopelle had produced a sufficient number of works that qualify as “automatist” that his style could be fully appreciated. This body of work can be grouped into two categories: watercolors with web-like black lines interwoven over masses of color, suggesting successive layers of depth; and oil paintings of extremely heavy consistency in which controlled randomness allows for the appearance of an unconscious, interior landscape — what the French surrealist artists called an “inscape.”

The painting Riopelle exhibited at Véhémences confrontées in 1950, a show at the Galerie Nina Dausset in Paris organized by the art critic Michel Tapié and the painter Georges Matthieu, was inspired by a Jackson Pollock painting Tapié described as “amorphique,” meaning formless or purely material. The description fit Riopelle’s painting better than Pollock’s. In a text accompanying the exhibition, Riopelle claimed that only “total chance” could open his painting to new discoveries. He then expressed the desire to detach himself from the automatists, though his paintings and technique remained faithful to the idea of complete spontaneity.

The Paris Years

In the 1950s, Riopelle developed his well-known, mature style of creating large, colour mosaic paintings with a palette knife and by squeezing colours onto the canvas directly from the tube. This approach gave his paintings a distinct sculptural quality. One such painting, Blue Night (1953), was included in Younger European Painters, an exhibition organized by James Johnson Sweeney at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1953. Shortly thereafter, Riopelle signed on with the Pierre Matisse Gallery (owned by the son of the great French artist Henri Matisse), which was devoted to French avant-garde artists in New York. Important New York art critics like Frank O’Hara, a poet and renowned curator at the Museum of Modern Art, recognized Riopelle’s importance and compared him to Jackson Pollock.

In Paris, Riopelle was close to various American expatriate painters, among them Sam Francis, who remained a close friend for the rest of his life. It is in this context that he met Joan Mitchell, with whom he had a stormy relationship that lasted 25 years. They both resisted the trend prevalent in the French avant-garde of the time to follow Picasso. Instead, they became interested in Monet’s immense paintings of his floating gardens in Giverny, near Paris.

In 1962, Riopelle represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. Throughout the 1960s, Mitchell and Riopelle maintained separate homes and studios near Giverny. The French art critics of the time coined the term nuagisme (from nuage, French for cloud) to describe Sam Francis’s, Joan Mitchell’s and Riopelle’s paintings, suggesting that they were less interested in form than in the diffuse effects of colour.

Return to Canada

In 1970, Riopelle exhibited a plaster version of his monumental sculpture, La Joute (The Joust), at the Galerie Maeght in Paris. The model was cast in bronze in Italy in 1974, and two years later installed at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium. In 1981, Riopelle received a large retrospective at the Musée National d’Art, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. It later travelled to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Over time, Riopelle visited Canada more and more frequently, first to hunt but also to paint. It was only in 1989 that he permanently returned to Quebec. His fascination with animals gave birth to numerous engravings that constitute a highly original bestiary, as well as many depictions of Canadian geese. He had a studio at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson (from 1974), at l’Estérel (from 1990), and finally at l’Isle-aux-Oies (1994–2002).

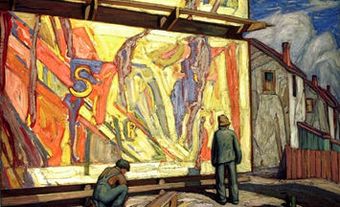

During his final period, Riopelle had stopped using palette knives and instead used spray cans, often spraying over objects set on the canvas. The public had difficulty understanding his late style. But when he painted his huge Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg shortly after hearing about the death of Joan Mitchell in 1992, it was impossible to deny that Riopelle had mastered a new technique inspired by urban graffiti. Hommage might be described as a coded message about his life with Mitchell. He purportedly liked to call her Rosa Malheur, a play on words on the famous animal painter Rosa Bonheur. What fascinated Riopelle about Rosa Luxemburg, on the other hand, is the fact that the great communist leader used to send coded letters to her partisans when she was in prison. The painting in three sections is now in the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

After Riopelle died on 12 March 2002 at Isle-aux-Grues, a state funeral was held in his honour. (See also Jean Paul Riopelle: Obituary.)

Legacy

Jean Paul Riopelle was the best internationally known Canadian painter of his era. His work is represented in all the great museums of the world. His paintings from the 1950s still sell for more than $1 million. In 2017, his Vent du nord (1952–53) sold at auction for more than $7.4 million, making it the second most expensive piece of Canadian art ever sold, behind Lawren Harris’s Mountain Forms.

Great retrospectives of Riopelle’s work — such as that which coincided with the opening of the Jean-Noël Desmarais pavilion at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in December 1991 — attract thousands of visitors. The publication of his Catalogue raisonné, in four volumes, under the direction of his daughter Yseult Riopelle, is also a sign of his enduring importance.

The Jean Paul Riopelle Foundation was created in October 2019 to “encourage and support experimentation and risk-taking in art-making, facilitating cultural partnerships with arts organisations and institutions, faculties and artists’ studios in Canada and around the world.” In 2021, the Foundation partnered with Concordia University to create an oral history archive about Riopelle and his work.

Honours and Awards

In 1958, Jean Paul Riopelle received the 1958 Prix International Guggenheim award. In 1969, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada. He received honorary degrees from Concordia University, the Université de Montréal, McGill University and the University of Manitoba.

Riopelle received the Prix Philippe-Hébert from Montreal’s Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in 1973, the Prix Paul-Émile Borduas in 1981 and the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris in 1985. He was made an Officier of the Ordre national du Québec in 1988 and was promoted to Grand officier in 1994. He was inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame in 2000.

On 7 October 2003 — what would have been Riopelle’s 80th birthday had he not died the in March 2002 — Canada Post issued a series of seven stamps in his honour. Each stamp features a different part of Riopelle’s monumental 40-metre-long fresco, L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg (1992). In 2004, a newly built public square in the heart of Montreal’s commercial district was named Place Jean-Paul-Riopelle in his honour. His sculpture, La Joute (The Joust), was relocated there from the Olympic Stadium.

In 2023, the Royal Canadian Mint issued a commemorative $2 coin to honour the 100th birth of Riopelle, whom it called “one of the most globally revered Canadian artists of the 20th century.” Like the stamp issued by Canada Post, the coin also features a portion of Riopelle’s L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg.

(See also Painting: Beginnings; Painting: Modern Movements.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom