Inventors and Innovations

Innovation is the successful application in a real economic or social context of something new that may or may not be an invention. Economic Council and Science Council investigations 1968-78 defined innovation as of fundamental importance in SCIENCE POLICY and special government programs were created to promote it.

In 1967 J.J. Brown's Ideas in Exile, a history of Canadian inventions, concluded that something wrong with the Canadian character had denied many good inventions the economic success they deserved. His assessment was not unique. It corresponds to the idea that Canadian artists, eg, actors and writers, are not recognized at home until after they have earned reputations in Europe or the US. Some sociologists such as S.D. CLARK attribute economic differences between the US and Canada to different social traditions.

History suggests Canada has produced many inventors and innovators. Simple examples include Anna Sutherland Bissell, inventor of the carpet sweeper, and Albert C. Fuller, founder of the Fuller Brush Co. He was an innovator (not being the inventor of the brush) and she both an inventor and an innovator, and manager of the Bissell Carpet Sweeper Co for several decades after her husband's death. Both developed their ideas and earned their fortunes in the US since its much larger market promised greater returns.

There is a long record of both successes and failures in Canada. Successes include the A.V. Roe Co's aircraft, the use of computers to design the St Lawrence Seaway, the CANDU nuclear reactor and Bell-Northern Research Ltd. BNR exemplifies some of the paradoxes of innovation. The Canadian telephone company began large-scale research chiefly because an American legal decision cut off the flow of free technology from US laboratories to Canadian factories in 1958. In the last 25 years BNR has become the largest research organization in Canada and earned a worldwide reputation as an innovator.

Five types of innovation were defined by the economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1911: a new thing; a new process for making a familiar thing; a new market to which to sell; a new source of supply or raw material; and industrial reorganization, eg, establishing a monopoly. Only the first 2 of these 5 types are likely also to be inventions. (The assembly line, usually attributed to Henry Ford, is not so much an invention as case 5, reorganization of the flow of materials through a factory.)

The Schumpeter scheme suggests how difficult it is for governments to support or promote innovation, even when they believe it an important agent of economic growth and prosperity. No rules have yet been devised to predict whether a firm (or a nation) would get more benefit by investing resources in a new invention or in something else, eg, marketing. Economic historians have recently suggested that, although there have been so many invention-based innovations in the last 100 years, they are relatively rare: most profits from innovation can be traced to the cumulation of many small improvements. The all-metal aircraft and the jet engine are notable inventions; but their economic success appears to depend on hundreds of small-scale improvements, not necessarily by the original inventors of the airframe and engine.

An illustration is the IBM Personal Computer, of which the unique components were the Intel 8088 computer chip and the MS-DOS operating system. Both these inventions came from other firms and neither was particularly advanced in 1981. In combination with IBM's reputation and its sales organization they constituted a revolutionary innovation. The results were both a huge new market for microcomputers and a new technological standard. Even so, IBM could not monopolize the benefits of its success, and may in fact have profited less than other firms adopting its standard.

Before 1960, most historical thinking about technology amounted to little more than anecdotes about inventions. When the systematic economic analysis of innovation began, science policy theoreticians hoped it would reveal shortcuts to economic prosperity and security. These hopes were disappointed. Current scholarship suggests that innovation is more an aspect of total systems than a separate function. It is possibly a skill like cooking - recipes and the chemistry of cooking can be scientifically analysed, but they do not make a good cook.

Innovation studies failed to discover what their pioneers wanted, but this makes Canada no worse off than any other country. The practical point is to use what has been discovered, along 2 main lines. One is that the general economic environment now seems to be more important than was previously assumed, and inventive genius is less important. Other important elements are luck, attitude and scale. We can never know how many potential inventors get disillusioned and give up. And the financial risks of innovation that a large firm could absorb might threaten the survival of a small firm. Industrial innovation is risky and expensive. Firms cannot afford to abandon their methods and machinery just because something new has been invented; at the same time they must recognize the risks of falling behind their competitors.

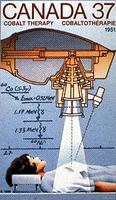

The other approach to managing or promoting innovation is awareness of its secondary characteristics: that economic and social benefits seem to depend on the total context more than individual inventions, and that innovation does not have to mean risking everything on brand-new technology. Detailed studies of new industries and the history of staple products such as wheat and steel suggest that greater economic successes have come more from the cumulation of dozens of incremental improvements than from each major technological revolution. This seems equally true of non-industrial domains such as health and medicine, which have also been transformed in the last 100 years. The benefits cannot be attributed exclusively to specific discoveries, such as antibiotics, independently from general principles, eg, infection, sanitation and scientific nutrition.

These general conclusions suggest that, even if innovations cannot be predicted, there is still scope for governments and business managers to cultivate the economic and cultural seedbed where innovations can happen. Important factors include the size of the domestic market, the structure of Canadian industry (eg, foreign control of certain industries), economic dependence on primary industries, psychological attitudes to risk (Canadians' preference to save money in life insurance or bank accounts, rather than investing in the stock market on the same scale as Americans) and the level of technical education, as well as political priorities.

For discussions of inventors and inventions, see the following articles: Thomas AHEARN; Alexander Graham BELL; Joseph-Armand BOMBARDIER; Gerald Vincent BULL; Karl Adolf CLARK; William Harrison COOK; Georges-Édouard DESBARATS; Charles FENERTY; Ivan Graeme FERGUSON; Reginald Aubrey FESSENDEN; Robert FOULIS; Abraham GESNER; William Wallace GIBSON; Frederick Newton GISBORNE; Uno Vilho HELAVA; INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT; George KLEIN; George Craig LAURENCE; Eric William LEAVER; PATENTS, COPYRIGHT AND INDUSTRIAL DESIGNS, ROYAL COMMISSION ON, Royal Commission on; Lloyd Montgomery PIDGEON; Frank Morse ROBB; Edward Samuel ROGERS; SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT; Sir William Samuel STEPHENSON; TECHNOLOGY; W.R. TURNBULL; T.L. WILLSON.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom