History

The exact year and location when and where Inuit vocal games began is unknown because the Inuit did not keep written records. However, some records of explorers and missionaries document vocal games in Alaska and the Canadian Arctic in the 19th century. Vocal games could also be found in Japan, among the Ainu, under the name rekkukara (or rekuhkara), and among the Tchukchi (or Chukchi) of East Siberia. Vocal games in Canada thus constitute evidence that the Inuit belong to a circumpolar cultural and musical civilization that reaches far beyond the present borders of this country.

Christian missionaries banned Inuit vocal games because they were thought to perpetuate non-Christian, non-white cultural practices. A resurgence of vocal games began in the 1980s among both elders and youth.

Terminology

First known to non-Indigenous people as guttural songs or throat songs (sometimes referred to as breathed songs), they were later designated more accurately as throat games by ethnomusicologists Beverley Diamond and Nicole Beaudry. Yet it is the Inuit term katajjaq that is most often used. However, it applies only to Arctic Québec and to the south of Baffin Island. Netsilingmiut (Netsilik), Iglulingmuit (Igloolik; Iglulik) and Kivallirmiut (Caribou Inuit) vocal games do not necessarily feature the throat sounds typical of katajjaq that are so striking; and they often refer to a narrative text absent from katajjaq. Thus, it appears simpler to adopt a more neutral and less specific term such as vocal game. In Inuit terminology, these games belong to the larger family of ulapqusiit (traditional games) and are designated more precisely as nipaquhiit, that is “games done with sounds or with noises” (nipi).

To say that they are both ludic and musical necessitates a comment. The Inuit have no generic term for “music,” but this does not deter ethnomusicologists and music lovers from their interest in the sound components of these games. It is, no doubt, for this reason that several recordings have, all or in part, featured these vocal games. However, this cultural takeover has created a distortion of the true dimension of these games within Inuit culture: first, because the drum dance remains the predominant musical genre and the vocal games constitute one game among others; and second, because ethnographically speaking, they are first and foremost used as spontaneous or playful practices, with winners and losers.

Performance

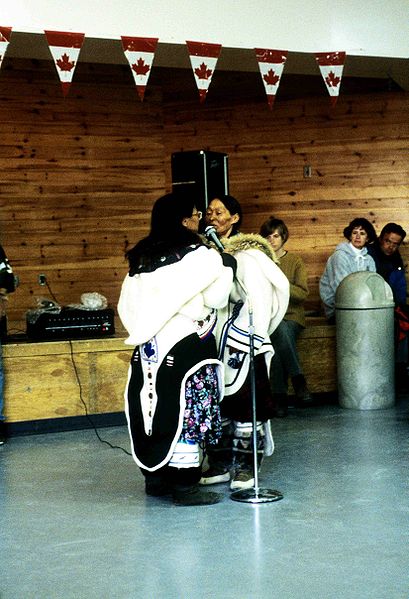

Generally then, vocal games are competitive activities, done most of the time by two women facing each other and standing very close to one another; sometimes they hold each other's shoulders. Contrary to widespread belief, it does not appear to be true that the partner's mouth served as a resonator. On the other hand, in certain regions (for example, where the Netsilingmiut and Kivallirmiut live), people use a kitchen utensil to transform the acoustical properties of the sounds produced (formerly they would use bags for carrying water made of caribou skin). The game stops when one of the women runs out of breath or laughs. Even if the spontaneous or playful dimension of the game remains predominant, the partners are nevertheless appreciated for their endurance and for the quality of the sounds they produce. One must win but with merit: certain sounds are considered more difficult to do than others. The game makes one even more breathless if the players drop on their heels and rise alternately. Whether or not these gestures are used seems to depend on the age and the physique of the players.

In certain regions (around Cape Dorset), the game could be played in teams: women who belonged to different camps, for instance, assembled to play the game, and the winning group was the one that forced the opposing team to make use of all its women. The game is played in pairs, but nevertheless four or more can play at the same time (in multiples of two). It seems that these games are essentially used by women, but this gender specialization results from the traditional way of life: boys also learned these games, but their participation declined when they reached the age to be able to participate in the hunt with adult males.

Categories of Vocal Games

Inuit vocal games can be divided in two major categories: katajjaq (or plural katajjait), practised around the coast of Arctic Québec, in the Belcher Islands, south of Baffin Island and, in a rather scattered fashion, in the rest of Baffin Island (where it might be called pirkusirtuk [or pirqusirtuq; pirqusirartuq]); and the Netsilingmiut, Iglulingmuit and Kivallirmiut vocal games, which are of a less homogeneous style. Some, but not all, types make use of story-telling texts.

Katajjaq

Katajjaq is basically constructed from repeated motifs (themes) and the succession of chosen morphemes (a word, or part of a word, that has a meaning). It also does not seem to follow a narrative logic (i.e. tell a story). The repetition of a motif (e.g., hamma) is characterized by a specific pattern of intonation and a pattern based on the alternation of sounds that are voiced (when the vocal cords vibrate) and un-voiced (no vibration of the vocal cords), and/or breathed in (sound made while inhaling) and breathed out (sound made while exhaling). The motif is repeated an undetermined number of times. Most of the time, the second voice's motif is identical to that of the first, but with an imitation-like time lag (of a half-beat) corresponding to the breathing-in, breathing-out alternation.

Since, in general, each motif contains a low-pitch sound followed by a high-pitch one (or the contrary), and since the two voices follow each other at a distance of a half-beat, those watching the game have the impression that they are hearing a chain of low-pitched sounds and a chain of high-pitched ones, whereas each sound has been produced alternately by each of the two partners. Without warning, one of the two players might decide to change her motif and the other partner must follow suit without breaking the rhythm. In spite of the competitive nature of the game, the resulting sound must project the feeling that there is perfect harmony between the singers and such uniformity of sound that the audience is not able to discern exactly who does what.

Concerning its meanings, it can be said that katajjaq acts as a sort of “open structure,” receptive to many diverse and pre-existing sound expressions, including meaningless syllables (or for which meanings are no longer understood), archaic words, names of ancestors or elders, animal names, toponyms (place names), terms designating an object seen while playing the game, animal cries (sometimes but not always geese calls), sounds from nature, the melody borrowed from an aqausiq (an affectionate song composed for an infant), the tune of a drum dance song or of a religious hymn.

Katajjaq was and still is done for all kinds of different occasions: anytime during the day; in any season; for sheer pleasure; to put babies to sleep; or upon returning from the hunt; in the qaggi (a dance or singing house; a party); in the form of team games; during extensive travels; or integrated within other series of games. Katajjaq was also used as respiratory training in bad climatic conditions. Some argue that in the past, katajjaq fulfilled some shamanistic function, participating in a kind of symbolic task division: while men were out hunting, women played katajjaq to influence the spirits of natural elements or of animals (named or imitated in the game); and thus, from a distance, contributed to the success of an essential survival activity.

Vocal Games of the Netsilingmiut, Iglulingmuit and Kivallirmiut

Among the Netsilingmiut, Iglulingmuit and Kivallirmiut, the great majority of the games collected by researchers tell a story. Frequently the text is distributed with a precise rhythmic articulation, which makes the game resemble what we call a sing-song. In many other cases, the same text is transformed with the breathing style typical of katajjait — the alternation of inhaled and exhaled sounds — without, however, their characteristic throat sounds. These games then act as enigmas or riddles and the listeners (children or adults) must reconstruct their meaning. In these regions, there are styles of narrative games based on texts that are similar from one village to the next (with variants, of course), including quananau, qiarpalik, illuquma and niaquinaq. Next to these narrative games are those games based on the juxtaposition of repeated morphemes designated by the first motif used (amerniaktok, angutinguark, haqalaktuq, immipijiutuq, iurnaaq, marmartuq, pirqusiqtuk, sirqusurtaqtuk, ullu, umpi, etc.); in these latter games, it is not possible to discover a clear discursive logic from one motif to the next.

Vocal Games Artists

In September 2001, Puvernituk, Nunavik, hosted the first ever Inuit throat-singing conference. Organized by the Avataq Cultural Institute, the conference brought together 100 Inuit throat-singers from different parts of the Arctic and of all ages, providing a cross-generational and cross-cultural experience. Their goal was to begin a movement to preserve Inuit vocal games and to form a national association of Inuit throat singers in Canada. Conference attendees produced a musical collection of Inuit vocal games, which boasts it is the most comprehensive recording of throat singing ever recorded.

Perhaps the most well-known Inuit throat singer in Canada is Tanya Tagaq Gillis. From Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, Tagaq is considered a “modern” throat singer because she performs katajjait without a partner. There are also well-known Inuit throat singers in Canada who perform traditional styles of music and song, including Karin and Kathy Kettler of the sister duo Nukariik.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom