The IODE is a national women’s charitable organization in Canada. Founded in 1900, the organization’s original intent was to support and promote patriotism to the British Empire. (See Imperialism.) The IODE contributed to the construction of an Anglo-Canadian identity in the image of Britain. Throughout this time, the IODE improved the lives of some women in Canada, and championed various causes, such as improving health care and producing strong Canadian citizens. However, the organization was, at times, complicit in racism and oppression. Increasingly aware of this problem, the organization changed its name to IODE in 1978-9 and became more Canada-centric. Today, IODE focuses on the welfare of children, education and community service.

Creation

The IODE was founded in 1900 by a Scottish-born Canadian woman, Margaret Polson Murray, a sometime journalist and philanthropist. Polson Murray was in England in 1899 when news of the first casualties of the South African War (Boer War) broke. Inspired by the patriotic sentiment of the moment, upon her return to Canada she began working to draw women together to support the British Empire. Polson Murray’s simultaneously nationalist and imperialist vision was for an empire-wide women’s organization centred in Canada. However, these plans were blocked by the England-based Victoria League, to which the IODE deferred. The group therefore remained primarily Canadian, though some smaller chapters (consisting largely of British expatriates) were established in pre-Confederation Newfoundland, the United States, Bermuda, the Bahamas and India.

Membership and Structure

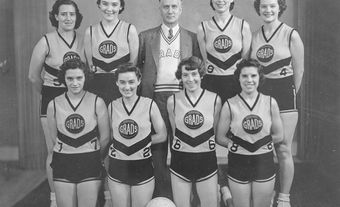

Polson Murray was married to John Clark Murray, an influential professor of philosophy at McGill University, and used her elite network to help the IODE launch and grow. As a result, the group was initially mostly composed of urban middle-class women who were married to elite males. Membership was largely by invitation and invited members could be voted in or out by ballot. In later years, intergenerational membership became quite common, with mothers recruiting daughters or daughters-in-law. Membership peaked at 50,000 during the First World War, declined to 20,000 during the interwar years, rebounded to 35,000 during the Second World War, and has steadily declined ever since.

Officially, membership in the IODE was open to “all women and children in the British Empire or foreign land who hold true allegiance to the British Crown.” In practice, membership was historically more restricted, depending on the time and place. Though officially non-denominational, at the outset the IODE was almost exclusively Protestant. Socio-cultural diversity was later accommodated through the creation of dedicated chapters, such as the Catholic chapters in Quebec, Jewish chapters in Quebec and Ontario, the Jon Sigurdsson Chapter of Winnipeg (composed of Icelandic immigrants), the Saint Margaret of Scotland Chapter of Alberta (composed of Hungarian immigrants), and the Native Chapter in British Columbia. (See Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Activities, 1900–45

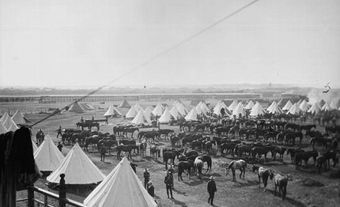

During wartime, the IODE has provided strong support for the Armed Forces. During the South African War, it worked to locate and mark the graves of fallen Canadians. Throughout the First World War, the IODE made outsized contributions of war materiel, beginning with a battleship. Members visited soldiers’ wives and families at their homes, worked to persuade men to enlist, actively campaigned for compulsory military service, and objected to the peace movement. As an organization, the IODE also associated itself with the Anti-German League and cut ties with groups that were affiliated with “enemy” nations.

From its inception, members of the IODE had greeted new immigrants to Canada at major ports of arrival. During the interwar period, the IODE became even more heavily involved with immigration and especially the “Canadianization” of immigrants, by which was meant their assimilation into Canadian society. Their efforts included travelling libraries, children’s newspapers, and patriotic pictures, films, lectures, short stories and plays. They also partnered with other women’s organizations to support women’s hostels, designed to protect immigrant women’s purity. (See Immigration to Canada.)

The IODE showed preference for middle-class British immigrants and worked with other organizations in Canada and the UK to pursue this goal. They also expressed alarm at the number of “foreigners,” namely continental Europeans, who made up the bulk of immigrants during this period. In this, they were influenced by theories of race science and eugenics and believed in a clear racial hierarchy, such as expressed in James Woodsworth’s, Strangers Within Our Gates. This led them to actively oppose the immigration of peoples of African and Asian descent. For instance, in 1911, the IODE petitioned the minister of the interior to block African American immigration to Western Canada. In 1923, the IODE supported politicians in British Columbia who successfully pressured the federal government to halt Chinese immigration. (See Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 — the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada; and Chinese Immigration Act.)

When the Second World War broke out, members of the IODE raised funds, knitted garments, supplied books and donated a bomber. They also welcomed British war brides, in some cases sending them wedding dresses. But the IODE national chapter also passed a motion calling for the federal government to repeat its First World War policy of interning all “enemy aliens and subversive naturalized Canadians.” The British Columbia Provincial Chapter asserted that people of Japanese descent (who had been interned) were unable to become “assimilated into Canadian life.” (See Internment in Canada.)

Postwar and Cold War Eras

In the immediate postwar years, the IODE was involved in memorialization of the conflict, through the creation of monuments and the expansion of their War Memorial Scholarship program. On other fronts, notable provincial projects included the 1947 study of child welfare in Alberta; its well-founded concerns led to a Royal Commission being established the following year.

As the Cold War heated up, the IODE founded two new committees: “Combatting Communism” and “Democratic Action.” Its anticommunist efforts included urging members to vote “wisely,” distributing pamphlets, organizing radio series, and encouraging participation in civil defence measures. The IODE continued to lobby the government to give preference to immigrants of British descent, and members remained actively involved in shepherding immigrants to full citizenship, with a presence from the ports to the citizenship courts.

From the late 1950s through the 1970s, the IODE turned their attention to Canada’s north, particularly the Northwest Territories, and attempted to assist the federal government in assimilating and “modernizing” Indigenous peoples living there, in part due to fears of possible Russian encroachment. Such efforts included funding the building of community halls, as well as local health and education projects and the donation of knitted goods. (See Inuit.)

1960s–Present

The IODE has “by a long stretch outlived the Empire that it was formed to defend,” as historian Katie Pickles put it, and its longevity has been credited to its ability to change with the times. Yet this was challenged most strongly in the 1960s as the organization’s backward-looking imperial focus became increasingly out of touch with Canadian society. As one member asked in a 1962 editorial in the IODE magazine Echoes: “Are we dinosaurs?” In 1964, the IODE argued that Canada was “not a multilingual or multicultural society” (though they supported official bilingualism and biculturalism as a means of resisting Americanization); and in 1965, they didn’t necessarily support the adoption of a new Canadian flag. Such concerns persisted: in 1981, for instance, the IODE saw no need for the repatriation of the Constitution. (See Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism; and Constitution Act, 1982.)

By 1970, the organization had developed a distinct sense of uneasiness about its history. It was insecure about its perceived influence and seeking to avoid “the inevitable WASP [White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant] label.” When submitting a brief to the federal government in 1971, the IODE sought the support of other groups, particularly those with non-British heritages. In 1978–9, the organization officially changed its name to IODE. At some point, the IODE acronym was reclaimed to stand for “Inclusive, Organized, Dedicated, Enthusiastic.” The organization became a registered charity in 1991 and adopted an official mission statement, which affirms their dedication to “enhancing the quality of life for individuals through education support, community service, and citizenship programs.”

In 2021, the IODE had 1,750 members in nine provinces and one territory, with six provincial chapters, one municipal chapter, and 101 primary chapters. Members volunteer time and provide over $1,500,000 dollars annually to support various charitable endeavours at the primary, provincial and national levels, including support for remote northern communities, hospitals, schools, shelters and special care homes.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom