Hutterites are one of three major Christian Anabaptist sectarian groups (the others are the Mennonites and the Amish) surviving today. They are the only group to strongly insist on the communal form of existence. The 2016 census recorded 370 Hutterite colonies in Canada. The total population living in Hutterite colonies was 35,010 people, with the majority located in Alberta (16, 935), Manitoba (11, 275), and Saskatchewan (6250).

History

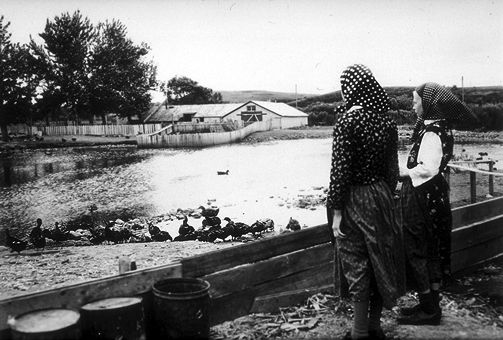

Hutterite history dates to 1528 when a group of about 200 German-speaking Anabaptists established a communal society in Moravia (now a region in the Czech Republic) to escape religious persecution. Under the initial leadership of Jacob Hutter, they established the basic tenets of Hutterian beliefs, which they have followed with little deviation to this day. These convictions, based on early Christian teachings and a belief in the strict separation of church and state, include a form of communal living, communal ownership of property, nonviolence and opposition to war, and adult baptism. Modern day Hutterites have retained the dress, customs, language and simple lifestyle of their ancestors.

Migration and Settlement

Because of their beliefs, Hutterites were subjected to periodic persecution which led to migration from their homelands. They moved from Czechoslovakia to Hungary, Romania, Tsarist Russia, the US, and finally to Canada.

While American Hutterites during the First World War were under suspicion for being "German," the Canadian government granted Hutterites freedom of worship, and from military service, in exchange for developing the land. This created a backlash from the previously settled population, though the end of the war eased hostilities. After 1918, some 50 families had emigrated to Canada, settling first in Alberta and Manitoba, then in Saskatchewan. By 1940, there were 52 colonies in Canada. The beginning of the Second World War, however, again brought an end to any goodwill towards the Hutterites.

Until recently, the basic nature of Hutterite settlements had been misunderstood, especially in regard to the relatively small amount of land that they own, and in relation to this, their productivity and contribution to the economy had been unappreciated. These misperceptions had resulted in the past in various restrictions and forms of discrimination against the Hutterites. In Alberta, for instance, Hutterite land purchase was restricted by the 1942 Communal Property Act until 1972.

In 1995, the total North American Hutterite population was about 30,000 — more than 66 per cent of whom lived in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, while the remainder were in the US. By 2011, the Hutterite population in Canada alone was 32,500. In 2016, the total population living in Hutterite colonies in Canada was 35,010 people.

Social and Cultural Life

Hutterites believe that their society can be best preserved in a rural setting, and hence agriculture has become a basic way of life. Their belief in communal living has led them to establish village-type settlements on each of their farms (or colonies, as they are known). In Manitoba the average size of a colony is about 1800 hectares (ha), but in Saskatchewan and Alberta, because of drier conditions, the colonies are each about 3600 ha. Despite these relatively large landholdings, each Hutterite family has less than 50 per cent of the land of a typical single-family farm on the prairies. The average colony has about 13 families with a total population of about 90. When the population of a colony reaches 125 to 150, the settlement subdivides and forms new colonies, which happens on average every 16 years. In 1995 there were 93 colonies in Manitoba, 54 in Saskatchewan and 138 in Alberta. By 2011, there were 345 across the Prairies – a 21 per cent increase. The 2016 census recorded 370 Hutterite colonies in Canada. Of these, 175 were in Alberta, 110 in Manitoba and 70 in Saskatchewan.

The Hutterite respect for the nuclear family is reflected in their provision of private apartments for each family in the row houses they traditionally build. Kindergarten facilities are provided for children from the age of two or two and a half years. The regular curriculum is studied in colony schools by all students, and since the 1990s, many now complete grade 12. In recent times computers have become a regular classroom feature in many colonies. A few Hutterites may proceed to take special diploma courses off the colonies in areas such as animal nutrition or veterinary science, and some take teacher training. There are now several fully qualified Hutterite teachers.

The structure of Hutterite colonies remains unchanged, although the nature of the economic activities in which they are involved may vary. Each colony elects an executive council from the managers of various enterprises, and together with the colony minister, the executive deals with important matters that will be brought before the assembly (all baptized male members - that is, men 20 years of age and older). Although women have an official subordinate status, their informal influence on colony life is significant. They hold managerial positions in the kitchen, the kindergarten, the purchase of dry goods, and vegetable production.

Economic Structure

Although there is co-operation among the colonies, each colony operates as an independent economic unit. The Hutterites practise a highly mechanized and efficient mixed-farming economy. Because of their well-managed, large-scale operations, when compared to the amount of land they own, the Hutterites produce more than their proportionate share of agricultural produce within the prairie economy. For instance, in Manitoba in 1991, Hutterites owned 144,920 hectares, or 1.9 per cent of Manitoba farmland, but they accounted for 9.5 per cent of the Manitoba farm population. In 1991 each colony had an average of 1,834 hectares. With an assumed 15 families per colony, each family had 122 hectares. This was slightly more than 40 per cent of the average Manitoba farm, which had 301 hectares.

To put Hutterite agricultural productivity in perspective, on this relatively small amount of land, in 1991, Hutterites accounted for over 25 per cent of the laying hens, over 25 per cent of the turkeys and 35 per cent of the hogs in Manitoba alone.

Group Maintenance

The survival of the Hutterites and their unique way of life is largely the result of their ability to retain their basic and fundamental beliefs, while simultaneously adopting all the features of contemporary society essential for their economic and social well-being. This strategy of survival includes uncompromising adherence to their religious beliefs and customs, retention of their ancestral German dialect, insistence on their own colony schools and a sound agricultural economy. Although some young people have always left the colonies, most used to return. As a result, assimilation was never a serious problem for the Hutterites. This may be changing as technology finds its way into traditional life and shows the diversity of the outside world.

Hutterites have adapted to technological change in different ways. Some colonies ban television, others allow it along with radio. Many use cellphones and the Internet, with varying degrees of restrictions. Online access has allowed Hutterite communities to interact with each other, while also introducing a way of life fundamentally different from their traditions.

See also Communal Properties Act Case.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom