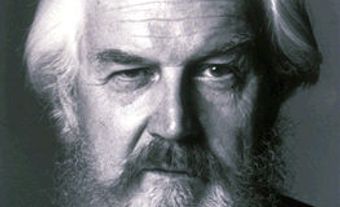

John Hugh MacLennan, CC CQ FRSL FRSC, novelist, essayist, professor (born 20 March 1907 in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia; died 7 November 1990 in Montreal, Quebec). Hugh MacLennan is best known as the first major English-speaking writer to attempt a portrayal of Canada's national character. A professor of English at McGill University (1951–81), he won five Governor General’s Literary Awards (three in fiction and two in creative non-fiction). MacLennan was also a Companion of the Order of Canada, a Knight of the National Order of Quebec, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Early Life and Education

Hugh MacLennan was born in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, to Samuel MacLennan, a physician, and Katherine MacQuarrie. His father was a strict Calvinist with ambitious plans for his son’s future. The family spent some time in London, England, and in Sydney, Nova Scotia, before settling in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

MacLennan’s education consisted of an ever-widening circle of experience that began in Nova Scotia, including classics at Dalhousie University. A Rhodes scholarship took MacLennan to Oxford University in England, from where he travelled on the European continent. His education culminated in a PhD in classics at Princeton University in New Jersey.

Writing

Hugh MacLennan returned to Canada in the mid-1930s to take a teaching job at Lower Canada College near Montreal. While there, he continued work on a novel, begun at Princeton, in which he hoped to convey his personal interpretation of all he had witnessed during his travels abroad. The failure to publish this novel — and an earlier one on a similar theme — induced him to take another tack.

The events that preceded the Second World War sparked him to recall what he had witnessed of the Halifax naval base during the First World War. By way of experiment, he wrote Barometer Rising (1941), focusing on the Halifax Explosion, which he had survived as a 10-year-old. The success of this shift from international to national subject matter (brought to the fore by the favourable criticism of American literary critic Edmund Wilson) led him to theorize that writers in Canada must now both set the stage and recite the country's dramas to the world. Barometer Rising and his essay collection Cross-Country (1949) ushered in a new phase in Canadian literature.

Did you know?

Hugh MacLennan ’s first wife, American-Canadian writer and painter Dorothy Duncan, encouraged him to write about Canada. Duncan was a published author herself, whose works included Here’s to Canada! (1941) and Bluenose: A Portrait of Nova Scotia (1942). Her biography of Czechoslovakian-Canadian Jan Rieger, Partner in Three Worlds, won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-fiction (creative) in 1944.

From then on, MacLennan would focus on aspects of contemporary Canadian life; however, he eschewed regionalism. "I have always seen Canada as a part of the history of the world," he maintains. Although Two Solitudes (1945) deals with English-French tensions in Quebec, The Precipice (1948) with puritanism in small-town Ontario and Each Man's Son (1951) with the Cape Breton mining community, each novel expands from its specific situation to consider, respectively, the rapid transition instigated by the First World War, the contrast between American and Canadian societies, and the effect of Calvinism.

With his last three novels — The Watch that Ends the Night (1959), Return of the Sphinx (1967) and Voices in Time (1980) — he increasingly moved outwards from the specific base of Montreal (where he taught in McGill University's English department from 1951 to 1981) to encompass those universal themes that arise from local political, social and human interests. Because his works transcend their particular settings, he became one of the most widely and most successfully translated Canadian novelists.

In the Thirties all of us who were young had been united by anger and the obviousness of our plight; in the war we had been united by fear and the obviousness of the danger. But now, prosperous under the bomb, we all seemed to have become atomized. Wherever I looked I saw people trying to live private lives for themselves and their families. Nobody asked the big questions any more. Why think, when the thing to be thought about is so huge it is impossible to think about it? Why ask where you are going, when you know you can’t stop even if you wish? Why ask why, when it does no good to know why?

From Hugh MacLennan’s The Watch That Ends the Night (1958)

Reception

Hugh MacLennan held a position of exceptional respect in Canada. He won the Governor General's Literary Award three times for fiction (Two Solitudes, The Precipice, The Watch that Ends the Night) and twice for non-fiction (Cross-Country and Thirty and Three). In 1984, he won the $100,000 Royal Bank Award, and in 1987, he became the first Canadian to receive Princeton University's James Madison Medal, awarded annually to a graduate who has distinguished himself in his profession. He garnered many other awards and honorary degrees.

Despite this success, critics have long debated the merit of his work. Many have endorsed Edmund Wilson's early praise; others have argued that the didactic aspect of MacLennan's fiction forces the stereotyping of characters, the predominance of the authorial voice, and reliance on outdated Victorian techniques of narrative and structure. Still others see MacLennan as overly ambitious in subject matter, especially in his treatment of French Canada, where his lack of firsthand experience is an artistic drawback. However, almost all critics have singled out MacLennan's skill in descriptive writing, whether of episode, action or natural landscape.

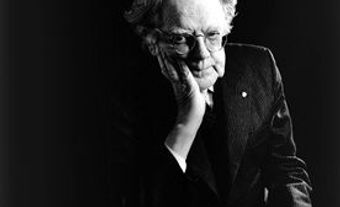

Although MacLennan was primarily a novelist, his essays (the best of which are collected in The Other Side of Hugh MacLennan, 1978) have elicited more consistent critical admiration. In these, he ranges over a variety of subjects with a civilized mind, impish humour, warm humanity and sharp intuition. He and Robertson Davies were Canada's finest essayists of the mid-20th century.

Ironically, MacLennan's own international aspirations are generally overlooked. As time passes, he has taken on mythic proportions as the Canadian nationalist who pioneered the use of Canadian scenarios in fiction. Writers such as Robertson Davies, Margaret Laurence, Robert Kroetsch, Leonard Cohen and Marian Engel owe MacLennan the sense that Canada is a place worth writing about.

Honours and Awards

Governor General’s Literary Award, Fiction (1945) for Two Solitudes

Governor General’s Literary Award, Fiction (1948) for The Precipice

Governor General’s Literary Award, Non-Fiction (creative) (1949) for Cross Country

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (1952)

Lorne Pierce Medal, Royal Society of Canada (1952)

Governor General’s Literary Award, Non-Fiction (creative) (1954) for Thirty and Three

Governor General’s Literary Award, Fiction (1959) for The Watch That Ends the Night

Companion of the Order of Canada (1967)

Royal Bank Award (1984)

Knight of the National Order of Quebec (1985)

James Madison Medal, Princeton University (1987)

Selected Publications

Fiction

Barometer Rising (1941)

Two Solitudes (1945)

The Precipice (1948)

Each Man’s Son (1951)

The Watch That Ends the Night (1958)

Return of the Sphinx (1967)

Voices in Time (1980)

Non-Fiction

Cross Country (1949)

Thirty and Three (1954)

The Scotchman's Return and Other Essays (1960)

Seven Rivers of Canada (1961)

The Colour of Canada (1967)

The Other Side of Hugh MacLennan: Selected Essays Old and New (1978)

On Being a Maritime Writer (1984)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom