North American Market

In May 1986 Canada and the US began negotiations for a bilateral free trade arrangement. A deal was reached in October 1987. It became the major Canadian election issue in the autumn of 1988. The Conservative government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney backed the accord and won the election; the deal came into effect on 1 January 1989.

Subsequently, the US and Mexico announced their intention to pursue a trade and investment liberalization arrangement. Canada asked to be a party to the negotiations. As a result, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed and came into effect on 1 January 1994, creating a huge free trade zone of about 370 million people. It extended and superseded the Canada-US Agreement after which it was modeled.

NAFTA is technically a free trade area, but with some of the attributes of a customs union—where member nations maintain the same duties and regulations regarding non-member third countries—and also some attributes of a common market—which allows for the free flow of factors of production (labour and capital) among the member nations. Examples of such attributes are the pressure for Canada and Mexico to conform to US tariff levels; the detailed rules of origin requiring high North American content for a wide range of consumer goods; the liberalization of services trade, including financial services and capital flows generally; and enhanced international freedom of movement for service and business persons and many professionals. The resource-sharing arrangements (particularly between Canada and the US) also suggest a common market in the making.

Access to US

Traditionally, free trade negotiations have focused upon the elimination of tariffs and quantitative restrictions on merchandise trade. But for Canadians exporting to, or desiring to export to the US, tariffs were not the main concern. Even before the free trade agreement, 80 per cent of Canadian shipments entered tariff-free and less than 10 per cent of exports faced US tariffs in excess of 5 per cent. Many of these were clothing, textiles, footwear and some petrochemicals. (Some commodities continued to face such high tariffs that they were not sold to the US at all.)

More important for Canada was obtaining secure and stable access to the vast and lucrative US market, without constantly having to fight American countervailing and anti-dumping duties—tariffs placed on Canadian imports deemed to be unfairly subsidized by Canada, or priced in some way as to present unfair competition to American industry (see Protectionism). Canada wanted agreement on what Canadian industrial subsidies would be free from countervailing duties. Canada also wanted US government procurement to be opened up to Canadian firms, and an effective and binding dispute-settlement mechanism that did not rest entirely on decisions made in the US.

Canada's Energy Sector

The US in turn wanted all trade in services and intellectual property included in the agreement; unhindered access for investment in Canadian industries, particularly the energy sector, without Canadian federal government surveillance or restrictions; and limits on government policies generally that might reduce US exports.

It was the expectation of many Canadians that more secure access to the US market would stimulate a range of efficiency-improving measures by Canadian manufacturers and thereby narrow the productivity gap between US and Canadian firms. Although new economies of scale have undoubtedly been achieved through the rationalization of Canadian manufacturing, and new technology has been adopted in Canada at a fast pace, the productivity gap with the US of about 25 per cent has not been narrowed.

Exports Boom

The liberalization process has nevertheless greatly expanded Canadian exports to the US. Between 1990 and 1995 such shipments grew 12 per cent annually, nearly twice the rate of growth of Canadian exports to the rest of the world. The greatest gains were in those industries where US tariffs were reduced the most. Exports of non-resource products have grown twice as fast as resource-based commodities, particularly the technologically intensive products such as office equipment, telecommunications products, precision instruments and a variety of other equipment and machinery. Some resource-based products such as fine papers and chemicals grew quite rapidly too. The result has been that Canadian dependence upon the US as a market for exports increased from 74.5 per cent in 1988 to 82 per cent in 1996. In 2010, The US remained Canada’s largest export trading partner, accounting for 74.9 per cent of total exports.

For service industries the removal of some non-tariff barriers, and the general stimulus of the free trade deal to Canadian firms to have a more export-oriented perspective, resulted in Canadian service exports to the US growing rapidly too, particularly financial services, consulting, communications and advertising.

Adding Mexico to the Canada-US agreement was not of great significance for Canadian exporters, since less than one-half of 1 per cent of Canadian foreign sales are to Mexico. The positive implications for the service industries, particularly financial services, are likely to be of more importance for the foreseeable future. In 2010, Mexico was Canada’s fifth-largest export destination.

Canadian imports from the US grew rapidly too, both in high-technology products and a number of labour-intensive industries such as furniture, clothing, processed foods and various household items. The result has been that Canadian dependence upon the US as a source of supply, which had remained at about 69 per cent of imports for several decades, increased to 76 per cent by 1996. In 2012, Canada was the US’s largest goods export market.

Imports from Mexico are somewhat more important for Canada than are exports to that nation. They amount to about 2.5 per cent of total imports, but are concentrated in relatively few sectors such as automotive parts, electrical machinery and equipment and some foodstuffs.

Canada Blocked From US Procurements

Canada was not successful in getting all government procurement liberalized. About 90 per cent of US government procurement is still not open to Canadian firms. On the other hand, although the US did not initially allow intellectual property included in the Canada-US agreement, during the negotiations to bring Mexico into the deal intellectual property was included.

No real progress has been made in defining what are acceptable subsidies, or in removing the applicability of anti-dumping and countervailing duty laws. Canada and the US had agreed to work more on these issues, but nothing came of this in the context of the free trade agreement. However, in the Uruguay Round of the worldwide GATT negotiations, stricter rules were developed on dumping, and permissible and non-permissible subsidies were defined.

A dispute-settlement mechanism was established so that bi-national panels review US and Canadian findings of dumping or subsidy, to ensure that each nation’s laws are administered correctly. This has worked fairly effectively except in some cases such as with Softwood Lumber and durham wheat, where the US has found ways of circumventing the free trade rules to limit Canadian exports. (Unlike in Canada where the free trade agreement effectively takes precedence over other Canadian laws, in the US other legislation takes precedence over the free trade deal.)

Canadian rules on foreign direct investment were liberalized so that few restraints remain on US firms wishing to establish themselves in Canada. Thus, since the agreement, thousands more Canadian firms have been taken over by US investors, and much Canadian direct investment has gone into the US, so that in this way too the degree of integration of the economies has increased.

Loss of Sovereignty?

Some Canadians believed a comprehensive free trade arrangement with the US would irreversibly erode Canadian economic, cultural and political sovereignty. Some would argue that this has not happened in that Canada has continued to protect its cultural industries (as provided for in the agreement), and to pursue an independent foreign policy in relation to nations such as Cuba.

Others say that even though Canada has become much more globalized in its orientation, it has increased its actual concentration of trade and investment with the US. It took the original European Common Market more than 30 years to move from a limited customs union to something now approaching complete economic and political integration under the leadership of Germany. Critics fear that over time, Canada could end up in a similar relationship with the US, which has a far more dominant role in North America than Germany has in Europe

Expanding Free Trade Networks

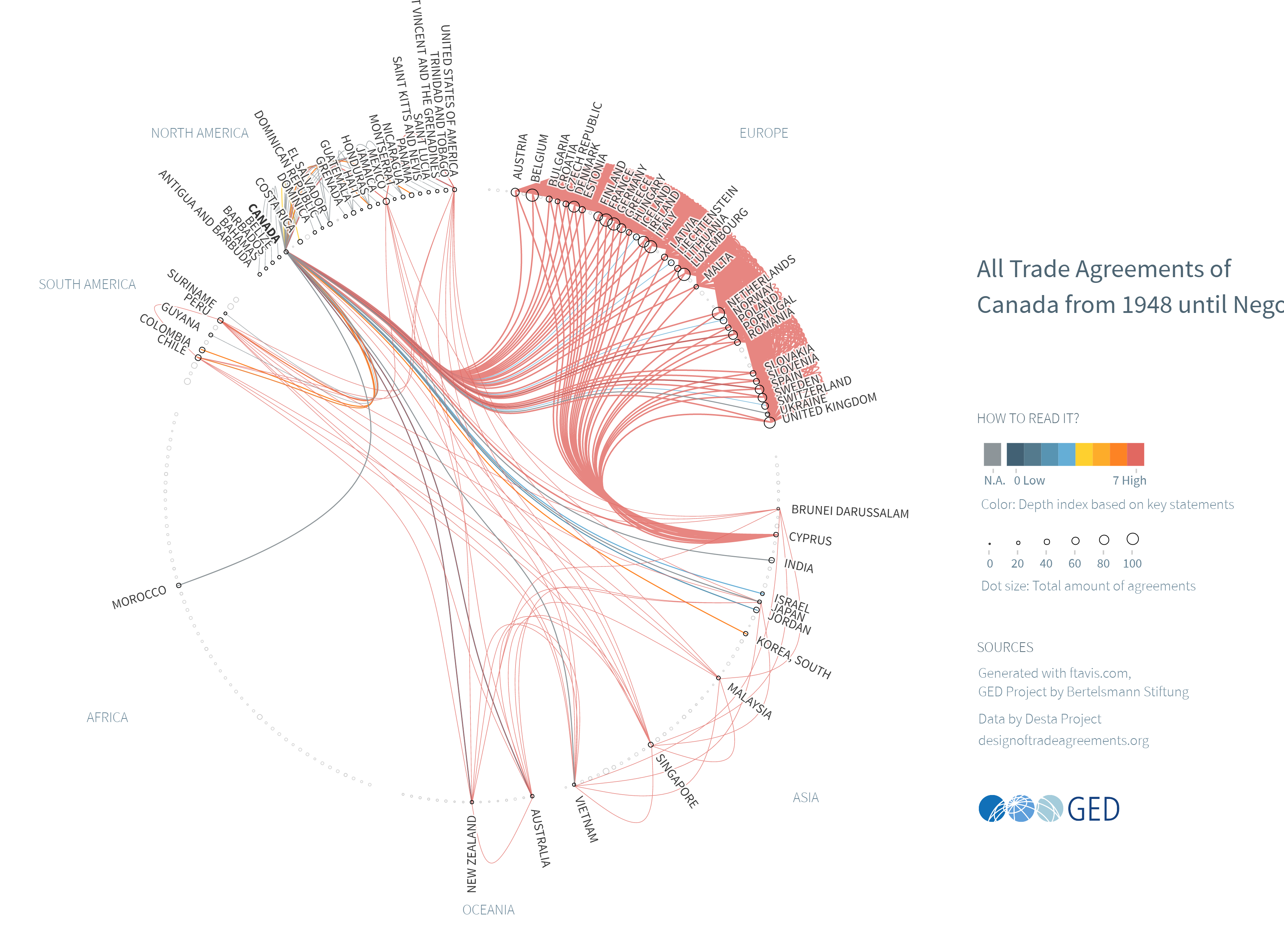

Canada is broadening its free trade relationships. The first of these is the bilateral free trade agreement struck with Chile in 1996. Essentially, the model of the NAFTA has been used for the Canada-Chile relationship. Canada negotiated a free trade arrangement with Israel in 1996 as well (something the US has had since 1985). However, both of these agreements have mostly symbolic significance at this stage, for Canada's trade with each of these nations is only about 1/7th of 1 per cent of the nation's total trade.

A more significant free trade agreement was reached with South Korea in March, 2014 -- Canada's first such agreement with an Asia-Pacific nation. South Korea and its 50-million people represent not only an important market for Canadian exporters, but the deal is expected to give Canada wider access to Asia through South Korean supply chains, particularly for agriculture, seafood and forestry producers. The agreement was criticized by Ford of Canada Ltd., which said South Korean auto makers will have cheaper access to the Canadian market, while being unfairly protected in South Korea through the use of non-tariff barriers and currency manipulation.

Canada has also entered free trade agreements with Costa Rica (2002), the European Free Trade Association (2009), Peru (2009), Colombia (2011), Jordan (2012) and Panama (2013). It remains in negotiations with more than a dozen other countries or free trade groups in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

See also Balance of Payments; Exports; Imports; International Trade; World Trade Organization.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom