Folk Dance

Folk dance exists on a variety of levels and folk dancers think of it in many ways. It is vernacular in that it is characteristic of a particular time and place and relates to a popular rather than an elite aspect of a culture. It also belongs to the "little" tradition within the "great" tradition of a society- it is primarily an oral or customary tradition, unwritten and unofficial. "Survival" folk dances are those that serve an integral function within a community; "revival" folk dances lack this stature and are performed by a select group of people who dance for various personal reasons. Many dance traditions involve elements of both survival and revival.Growth From Religious Rituals

One result of an oral as opposed to a written tradition is that people see, hear and perform differently; therefore, they transmit the material in a variety of ways. With folk dance, no particular version of a dance is the definitive one. If variants do not exist, then a dance was undoubtedly passed on in a nontraditional way, perhaps by written official sources or by a group that zealously guarded its "purity." Although documents that record the historical development of folk dance are scarce, some researchers believe that many dance forms grew from religious rituals. Each cultural area passed through its own evolution, although some areas have had more contact with external influences than others.

Social dance, although not usually considered so, is normally a form of folk dance existing at several levels. Dance studios claim to teach the "right" way, but in practice people invent, simplify and change, thereby creating variants of dances such as the waltz, cha-cha, disco or jitterbug. Social dance is part of the "little" tradition in a culture, and is vernacular. In the western European tradition, social dance is performed in couples and its usual function is courtship, a valuable ritual. Social dancing can be executed as a performance or in competition, often called ballroom dance.

Many social dances enjoy a short but intense popularity which then declines. Others, however, possess an unusual longevity: the waltz, polka, square dance and longways forms and the minuet of the 18th and 19th centuries are good examples. Not as popular as it was in past periods, social dancing is still considered a convenient and acceptable way to meet people. Companies, clubs, university groups, high schools and community centres host social dance events regularly.

Survival Folk Dance in Canada

In Canada, with the exception of social dancing, there is little survival folk dancing; it is difficult to determine precisely the amount of survival dancing that remains. However, it is found among relatively isolated (geographically or psychologically) communities such as native peoples and in francophone and Hassidic cultures. Urban-based minority groups such as Indian, Chinese, Italian, Portuguese, Ukrainian, Macedonian, Greek, Polish, German, Armenian, Irish, Latin-American and West Indian may have retained some of the dances unique to their regional origins. But as first- and second-generation immigrants die off, third and subsequent generations tend to assimilate into mainstream society, and with them go the dances which were once an important part of their social, occupational or religious spheres.

Revival dances are more frequent and more visible. They are especially noticeable among groups who have strong feelings for their ethnic roots. One way to preserve, express and perpetuate this sentiment is to perform "national" or "ethnic" dances. Dances may be acquired either when older group members recall dances from the past, or when an outside expert is summoned to teach the dance. The dances are then "set" for the group, which enjoys dancing them on suitable occasions.

Another area of activity is "international" folk dancing, performed by people who seek not cultural identity but the enjoyment of dances from many countries. A large proportion of these dances are from the Balkans, for line dances with intricate footwork seem to hold the greatest attraction. Again the dances are "set" by an expert, and as such are indicative of only one of the possible variants to be found in the native milieu.

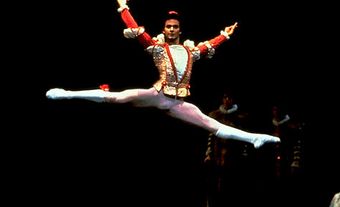

A third type of revival dancing involves the groups whose goal is to execute the dances "perfectly," eg, square dance clubs. Here participants casually perform for each other, although some groups have costumes for more formal, presentational occasions. Another type of group whose emphasis is on perfection is the theatrical folk dance troupe. Choreography, costumes and lighting designs combine to create a particular effect. Dances are presented in a highly theatrical manner, and sometimes several dances are combined into one.

The labelling of this material as "folk dance" is perhaps misleading, since it is "set" and variants are not encouraged. A better designation might be "folk-inspired" or "folk-derived" dance, labels that might help audiences to discriminate between theatrical presentations and survival folk dancing. In spite of these limitations, perfection-oriented groups express a vernacular form of dance within the "little" traditions of society, and this can be classified as folk dance.

The French Canadian dance tradition is a good example of a culture with both survival and revival forms. In Québec, folk dances are those based on square and longways formations, on sung-circle dances, and on the percussive, rhythmic pattering of the feet called step dancing or gigue. Many of these dances have an elite and noble history, such as the complex quadrille of Ile d'Orléans. Simpler square dances and others such as the longways la contredanse and le brandy probably involve British or American influence. All of these styles have emerged as folk dances, complete with variants and a paucity of documentation.

The gigue is traditionally passed down from parent (usually father) to child. Though its origins are not certain, it seems likely that it derives from the Irish jig. Because the gigue has always been an oral dance form, contemporary manifestations clearly demonstrate the process of a folk tradition - a vibrant dance form where structural and stylistic variants abound. Sung-circle dances, which were once popular with adults, have now mostly passed into the children's repertoire. A couple of adult rondes have been documented in isolated communities and from time to time are resurrected at workshops. Some of these dances represent part of the rich store of culture brought from France in the 17th century. Survival dance in Québec usually revolves around the home veillée, where dancing is one of many activities such as gossiping, eating, card playing and music.

Dancing serves as a catalyst to socialization, an important aspect of individual and community development. Today, as a result of television, smaller families and a rejection of "old-fashioned" ways, many "dancing families" no longer dance. There is, however, an active revival movement. The workshops sponsored by the Fédération des loisirs-danse du Québec emphasize learning the dances and having fun.

The Performance Troupe

The performance troupe has been a popular entertainment spectacle in Québec for many years. In the 1950s les Folkloristes du Québec were the first to theatricalize, in that they wore period costumes. Later, troupes such as les FEUX FOLLETS, les Danseurs du St-Laurent, les Gens de mon pays and the present les Sortilèges performed to enthusiastic audiences.

In English Canadian folk dance, the square dance is the most widely disseminated dance, popular from Newfoundland to BC. However, recent growth of the step dance contest, especially in Ontario, has catapulted this form into the limelight. Step dancing is an interesting mixture: it is both a vehicle for performance and a dance in a constant state of evolution. Younger contestants usually take lessons from experts, or learn from within the family. Only the "old timers" purport to dance in a traditional or old-fashioned style, while the others appear to have some of the exhibitionistic tap dance influence. Nontraditional taps are worn on the shoes in order to accentuate the sound. The music remains within the folk genre - a certain amount each of hornpipe, jig and reel. Only the tempo is increased.

Native Dance

Native peoples' dance is often connected with important rituals. Some dances can be shared with other tribes or with non-natives. The most visible occasion for folk dancing is the pan-native POWWOW, where prizes are won by dance competitors and there is dancing for noncontestants. The BLOOD of Alberta, for example, present 2 types of dances at powwows: collective solo dances such as the Sioux Dance, Grass Dance and War Dance, and couples ring dances, such as the Owl Dance. Another opportunity for powwow dancing is at the annual SUN DANCE, where many of the younger participants are unfamiliar with ritual dancing. Pan-native powwow dancing limits the attention given to specific tribal dances, but promotes identification with general native culture.

Non-native folk dances are also popular among some tribes. Square dances are probably the most pervasive; they have been reported among the Blood as Spi-ye-Buska/Mexican Dance and among the HARE at Fort Good Hope. The Hare also enjoyed the 2-step, waltz, jive and Scots reel.

Across Canada, then, there are many types of folk dance activities. Dancing is usually associated with an ethnic community, and often parents encourage children to participate in folk dance as a means of learning about and identifying with their cultural heritage. Elementary school children in general are obliged to learn squares or other types of folk dance, depending on their teachers' expertise. Carefully graded record and book sets are available to interested educators. The children usually perform these dances without much information about the original cultural context.

Clubs and Societies

Clubs and societies cater to the revival in folk dancing. A mid-1980s publication, the People's Folk Dance Directory, has compiled an extensive list of folk dance places, teachers and societies for both the US and Canada. Though useful as a general guide, the directory is far from comprehensive since many groups are unmentioned.

Along with regularly scheduled folk dance classes, special events such as folk festivals and ethnic celebrations are open to folk dance enthusiasts. Some of the more easily identified festivals include the Irish feis, Scottish highland dancing contests, May Day festivities (often involving English Morris dance teams), Québec winter carnival, Caribana and Israeli Independence Day. Other events, such as Caravan in Toronto, Man and His World in Montréal, and Folk Fest in BC, are multicultural and provide an opportunity to watch and participate in the activities of a variety of cultures.

The university campus is often a major force in the folk dance community, sponsoring clubs that are usually open to all. Academically, faculty and students at U Laval (Québec) and Memorial U (Newfoundland) have researched dance in their regions, and dance departments at York and Waterloo have also contributed to folk dance studies.

Several umbrella organizations both prepare folk dance events and act as a storehouse and information centre on activities in the area. The Canadian Folk Arts Council has branches throughout Canada, with head offices in Toronto and Montréal that have documentation centres. The Ontario Folkdance Association publishes Ontario Folkdancer, a magazine/newsletter that includes notices of events across Canada and in parts of the US. In Montréal the Fédération des loisirs-danse du Québec organizes soirées and weekend workshops, houses archival material and publishes a journal.

See also FOLK MUSIC.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom