Federalism is a political system. In it, the powers of government are split between federal and state or provincial levels. The federal (central) government has jurisdiction over the whole country. Each provincial government has jurisdiction over its population and region. In a true federation, the smaller states are not sovereign. They cannot legally secede. Canadian federalism has swung between centralizing control and decentralizing it. Both levels of government get their powers from Canada’s Constitution. But it includes features that do not fit with a strict approach to federalism.

Establishing a Federal Union

The Constitution of the United States (1787) is the first example of a modern federal constitution. A federal union of the British North American colonies was first conceived in the early 19th century. It was pursued more seriously from 1857 onwards. Negotiations among the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia took place at the Charlottetown Conference and the Quebec Conference in 1864. These discussions led the British Parliament to pass the British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867). It united those three colonies into a federal state as of 1 July 1867.

Confederation marked the start of Canadian federalism. The main goals of the union were to pave the way for economic growth, territorial expansion and national defence. However, many people wanted to keep existing governments and boundaries. There were various reasons for this. French Canadians held a strong majority in Quebec. They did not want to place all powers in the hands of a central government in which they would be a minority. There was also a strong sense of identity in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Federalism was therefore a compromise for many.

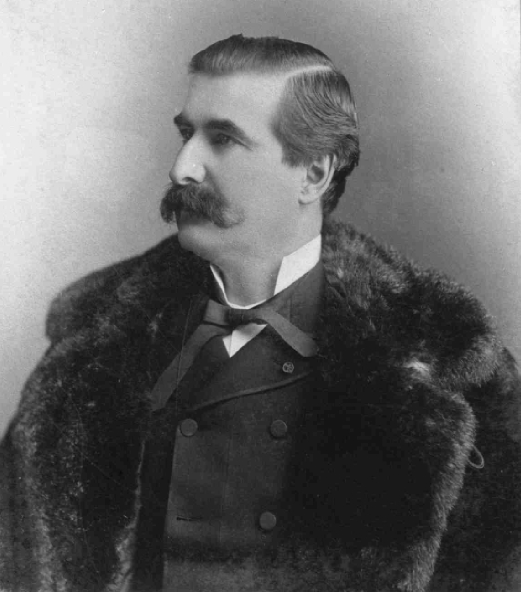

Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, was not keen on federalism. He preferred a unitary state. In this model, provinces would get their authority from — and would be subordinate to — the central government. Another key factor was the American Civil War. It saw the Southern States secede from the federal union. This led to the fear that giving the provinces too much power would make the country unstable. For these reasons, the Canadian Constitution includes features that do not fit with a strict approach to federalism.

Unused Unitary Powers

The lieutenant-governor of each province is appointed by the federal government. The lieutenant-governor can stop provincial laws from taking effect until the central government has approved it. The central government can also disallow any provincial law within a year of its passage. (See Disallowance.) Parliament can pass laws related to education within a province to protect the rights of religious minorities. It can also declare that “works and undertakings” in a province fall under its jurisdiction. It can do this regardless of the normal distribution of powers.

Because of these unitary features, the Constitution Act, 1867 has been described as quasi-federal. However, the quasi-federal powers are now rarely used.

Competing Concepts

Canadian politicians have expressed different versions of Canadian federalism. These differences of opinion have been sharper in Canada than in most federations. They have also been around for a longer period. No consensus has ever been reached about the appropriate relationship between the two levels of government. National and provincial politicians also tend to hold different views on the matter.

Macdonald’s quasi-federal concept was closely linked with the Conservative Party until about 1900. By then, the men who drafted the BNA Act were no longer influential in the party. Quasi-federalism also had little support during the 20th century.

However, a centralist view of federalism continues to enjoy great support. It stresses the importance of a strong and active federal government. Modern centralists normally avoid the quasi-federal powers of disallowance and reservation. Instead, they argue for a broad reading of Parliament’s powers. They believe that the federal government should be able to: make policy in its areas of jurisdiction without checking with the provinces; have access to most of the revenue from taxation; and make conditional grants to provinces even in matters outside its jurisdiction.

Central Versus Provincial

The authors of the BNA Act wanted the federal government to be more powerful than the provincial governments. Yet over time, the provinces grew in power. This was partly due to the growing importance of areas of provincial jurisdiction (such as social programs and natural resources). It was also due to a series of court rulings that favoured the provinces. (See Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.)

A centralist view of federalism was expressed in the 1940 report of the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations (the Rowell-Sirois Commission). Since then, centralist ideas about federalism have been strongly held in the Liberal Party. The New Democratic Party also tends toward a centralist position. Politicians and political thinkers who advanced a centralist concept of federalism include Louis St-Laurent, Francis Reginald Scott, Eugene Forsey, David Lewis, Bora Laskin and Pierre Trudeau.

Sir John A. Macdonald’s view that the provinces should be subordinate to the federal government was controversial from the start. In the early 1880s, a Quebec judge, Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger, wrote that the central government had been created by the provincial governments. He argued that no increase in the central government’s powers, and no change to the Constitution, was allowed without the unanimous consent of the provinces. This view became known as the compact theory of Confederation. It was expressed at the interprovincial conference of 1887.

A similar view was expressed by some of the premiers during the talks in 1980–81 to patriate the constitution. The emphasis on provincial autonomy was common in the Progressive Conservative Party after 1939, and in all provincial parties in Quebec. The Reform Party also held this stance. Supporters of decentralization think that the functions of the central government should only be ones that the provincial governments cannot perform for themselves, and that its control over revenue should also be restricted. They have also argued that the central government should consult the provinces before launching major policies. (Endorsements of decentralization can be found in the 1956 report of the Quebec Royal Commission on Constitutional Problems, and in the 1979 report of the Task Force on Canadian Unity.)

See-saw Struggle

In practice, Canadian federalism has swung between centralization and decentralization. This has happened due to various political, economic and social factors. Sir John A. Macdonald’s desire for a highly centralized regime reigned for a few years after Confederation. But by the 1880s, the provinces were as powerful as their US counterparts, if not more so. Provincial control over natural resources led to largely self-contained provincial economies. This was especially true after 1930, when Alberta and Saskatchewan took over control of their resources. The high volume of manufacturing in Ontario also made its government important and influential.

Worsening relations between francophones and anglophones undermined Macdonald’s Conservative Party. It also increased anti-centralist feelings in Quebec. Centralization was revived during the First World War and immediately after. The federal government levied an income tax for the first time in 1917. It also imposed conscription and took unprecedented control over the economy.

These actions were largely reversed after 1921. The Great Depression showed that the federal government lacked the power to deal effectively with a severe economic crisis. Efforts were made to ensure that centralization during the Second World War would last longer than it had after the First World War. For example, the federal government took all revenue from personal income tax from 1941 until 1954. Constitutional amendments gave Parliament the power to establish employment insurance and universal pensions. These programs were financed from a special fund in 1940 and 1951, respectively.

The BNA Act was widely seen by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as favoring provincial autonomy. But this ended in 1949, when the Supreme Court of Canada became the highest court in the country. During the post-war period, many grants were given to the provinces to encourage spending on health and welfare. Federal grants were also given directly to universities.

Shift to the Provinces

A shift of power in favour of the provinces became clear after 1960. The Quebec government led by Jean Lesage was dynamic and active. It was an effective opponent of centralization. Other factors included the growing importance of provincial natural resources; the decline of the old financial elite based in Montreal (see Laurentian Thesis); economic integration with the US; and a more competitive national party system after 1957.

Between 1960 and 1980, there was a large increase in the provincial share of taxation and public spending. Grants to universities were instead given to the provinces. Quebec opted out of certain grant programs and got unconditional grants in return. It also started its own pension plan. (See Quebec Pension Plan.) The federal government then established one for the people in other provinces.

Meetings between the prime minister and premiers happened more often. (See First Ministers Conferences.) This came to be known as “executive federalism.” Provinces became more aggressively involved in their own economies. They also challenged the right of the federal government to make economic policy without their consent. Provinces engaged much more with foreign governments. This was especially true of Quebec. After 1972, the dramatic increase in Alberta’s oil and gas revenues led to other strains on the federal system. It also led to contempt between Alberta and the federal government. The success of the Parti québécois, a major party that pursued Quebec separatism, suggested that the survival of Canadian federalism could not be taken for granted.

Patriation of the Constitution

Around the world, shifts in economic and political power usually lead to formal changes in a country’s constitution. In Canada, the trend toward decentralization had begun by 1960. Not long after, demands for a formal transfer of powers to the provinces became widespread in Quebec.

At the time, almost all of the other province had no interest in constitutional change. This led to the idea that only Quebec would receive more powers, and therefore had “special status.” After 1972, the rise in natural resource revenues led some of the provinces to demand more powers in a changed constitution. Alberta was the most vocal in this regard.

In response, between 1968 and 1981, the federal government held conferences with the provinces on constitutional change. It agreed to discuss a new distribution of powers. But it insisted that a charter of rights and the restructuring of national institutions also be on the table.

A related problem was the lack of an amending formula (the rules for changing things) in the Constitution Act, 1867. In other words, the criteria that would have to be met to make a legal change to the constitution had not been set. Efforts were made at the negotiations to come up with such a formula. This was needed to “patriate” the Constitution (take control of it from Britain) — a matter that had been discussed as far back as 1927.

In 1980, the government of Pierre Trudeau tried to patriate the Constitution. It proposed an amending formula that would require the support of Ontario, Quebec, two Western provinces and two Atlantic provinces to make any future change. It would also add the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to the Constitution.

This idea came after the talks about the new distribution of powers broke down. It was opposed by eight provinces (the Gang of Eight). It was also ruled unconstitutional, but not illegal, by the Supreme Court. (See Patriation Reference.) As a result of further talks, qualifications were added to the Charter of Rights. An amending formula was also added. It required the approval of seven provinces with at least half of Canada’s population (the 7/50 rule). However, provinces were also allowed to exclude themselves from applying changes that would reduce their powers.

All provinces except Quebec accepted this compromise. It took effect when the constitution was patriated on 17 April 1982. Quebec felt the federal concessions were not enough. It opposed adding language rights for English-speaking Quebecers. The Supreme Court ruled that Quebec’s consent had not been required to amend and patriate the constitution. Despite that, efforts to gain Quebec’s signature resumed in 1986.

Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords

These efforts led to an agreement among the 11 first ministers in the Meech Lake Accord of April 1987. It would have recognized Quebec as a “distinct society.” It would have allowed the provinces to help appoint senators and Supreme Court justices. It would have restricted the federal power to spend in areas of provincial jurisdiction; recognized provincial powers over immigration; and made slight changes to the amending formula. ( See also Meech Lake Accord: Document.) However, a growing number of interest groups, Indigenous people and Newfoundland premier Clyde Wells strongly opposed the Accord. They scuttled it in June 1990. (See Editorial: The Death of the Meech Lake Accord.)

A second round of talks among the premiers and the federal government led to the Charlottetown Accord. It was soundly beaten in a national referendum in 1992. (See also Charlottetown Accord: Document.) Many public forums and commissions were held to help Canadians reach a greater consensus. But they exposed even greater divisions.

The separatist movement in Quebec seemed to lose strength after the failed 1980 referendum. But it re-emerged after the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords failed. This time, the cause was pursued at the federal level by the Bloc Québécois. The Conservative government of Brian Mulroney had briefly calmed Western protest. But it resurfaced over opposition to the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and with the rise of the Reform Party.

The federal Liberal Party won a large majority in 1993. But it faced two strong parties in the House of Commons. The Bloc Québécois and the Reform Party both held radically different views of federalism. After 1993, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien did not return to the centralist policies of the Pierre Trudeau era. (Some of them were no longer allowed under NAFTA.) Instead, it reduced the federal deficit by lowering spending on social programs. It also transferred some federal functions to the provinces or to the private sector.

Conclusion

The patriation of the Constitution and two other rounds of negotiations did not bring Canada any closer to resolving the question of how federalism should evolve. A second Quebec Referendum on sovereignty in 1995 revealed widespread dissatisfaction with federalism.

Those who support more provincial autonomy stress the diversity of all the provinces’ interests. They argue that the distribution of powers between the two levels of government needs to be brought into line with what they view as socio-economic realities. In their view, the result would be a more stable and legitimate political system.

Those who support keeping or expanding federal powers argue that decentralization is more the cause than the result of interprovincial diversities. They argue that decentralization ignores the many common interests of Canadians. They feel these interests can be stewarded most capably by a strong central government. They also argue that excessive decentralization weakens Canada’s economy and its influence in the world.

It is unlikely that these differences of opinion will soon be resolved.

See also: Constitution of Canada; Constitutional History; Constitutional Law; Constitutional Monarchy; Peace, Order and Good Government; Statute of Westminster; Constitution Act, 1867 Document; Patriation Reference; Patriation of the Constitution; Constitution Act, 1982; Constitution Act, 1982 Document.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom