Domestic work refers to all tasks performed within a household, specifically those related to housekeeping, childcare and personal services for adults. These traditionally unpaid household tasks can be assigned to a paid housekeeper (the term caregiver is preferred today). From the early days of New France, domestic work was considered a means for men and women to immigrate to the colony (see History of Labour Migration to Canada). In the 19th century, however, domestic service became a distinctly female occupation (see Women in the Labour Force). From the second half of the 19th century until the Second World War, in response to the growing need for labour in Canadian households, British emigration societies helped thousands of girls and women immigrate to Canada (see Immigration to Canada). In 1955, the Canadian government launched a domestic-worker recruitment program aimed at West Indian women (see West Indian Domestic Scheme). In 2014 the government lifted the requirement for immigrant caregivers to live with their employer to qualify for permanent residence — a requirement that put domestic workers in a vulnerable position. (See also Canadian Citizenship; Immigration Policy in Canada).

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

History of Domestic Service in Canada

Domestic work was a way for men and women to immigrate to New France (see History of Labour Migration to Canada; Population Settlement of New France). Domestic service, however, became a distinctly female occupation in Canada during the 19th century. Whereas in the 1820s approximately one-third of colonial servants were male, by the late 19th century more than 90 per cent of Canadian servants were female. Domestic service was the most common form of paid employment for Canadian women before 1900 (see Women in the Labour Force; Work). For example, in 1891, there were nearly 80,000 women working as domestic servants in Canada.

In the 20th century, with the increase of women entering factory, office and shop work the proportion of women working as domestic servants decreased. In 1891, 41 per cent of employed women worked as domestic servants and by 1921 only 18 per cent. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, British child-emigration societies as well as Canadian orphanages placed children into service (see Emigration, British Home Children; Child Migration to Canada; Child Labour.)

The decline in domestic work was most pronounced after the Second World War, which coincided with an increase in the number of live-out domestic workers and part-time work. Most live-in domestic workers were young women who performed general work in one or two households situated in urban centres or on farms. A small minority of domestic workers had specialized positions as part of a large staff.

Employers hired domestic servants to confirm middle-class status as well as to obtain needed help. The private employment conditions and general devaluation of housework made domestic service unpopular. Objections to low social status, unregulated hours, isolation and lack of independence remained unchanged over time. As a result of these conditions, after the Second World War, there was a shortage of domestic servants in the country. This led to the employment of immigrant women from Britain, Scandinavia and central Europe (see Immigration to Canada).

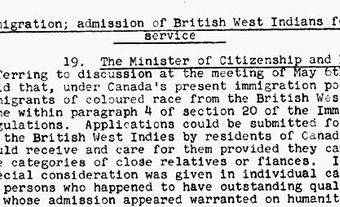

In the 1950s, immigration programs, such as the West Indian Domestic Scheme, recruited Caribbean women to work as domestics in Canada. Similarly, the federal government’s 1981 Foreign Domestic Movement Program, renamed the Live-In Caregiver Program in 1992, enabled approximately 30,000 Filipinos to immigrate to Canada between 1982 and 1991. (See also Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Programs; Immigration Policy in Canada.)

Temporary Visas and Immigration Programs

The policy of welcoming immigrant domestic workers as permanent residents changed in the 1970s when the government introduced temporary employment visas (see Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Programs). These visas allowed domestic workers to stay in Canada for a limited period, but only on the condition that they retain their employment as domestic workers. The government, accused of condoning the racial exploitation of West Indian and Filipino women, adopted a policy amendment in 1981, Foreign Domestic Movement Program (FDM). Through the FDM, foreign domestic workers, who had been working in Canada as live-in domestics for two-years, could apply for permanent resident status. In 1992, the FDM became the Live-In Caregiver Program. Under the Live-In Caregiver Program, foreign domestic workers had to complete two-years of live-in domestic work and upgrade their skills to show their “self-sufficiency.” The policy changes restored entry into Canada through domestic work, but they continued to devalue the worth of domestic employment. (See also Immigration Policy in Canada; Canadian Citizenship.)

Who has been looking after Canada’s kids? Leah and Falen find out that Indigenous women and women from all over the world took on this job, and none of their stories follow the plot line to Sound of Music. From Confederation to present day, has anything changed for these workers?

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Legislative Controls

The stigmatized, isolated and usually temporary quality of domestic labour has made it difficult to improve the work conditions of immigrant caregivers. The domestic science movement in the early 20th century unsuccessfully tried to professionalize domestic service. Early domestic worker organizations in Vancouver and Toronto were short lived, but beginning in the 1980s, INTERCEDE (International Coalition to End Domestics’ Exploitation) monitored conditions and achieved some legislative control of employment standards. (See also Employment Law; Work.)

After 30 November 2014, the Live-In Caregiver Program was changed, and immigrant caregivers were no longer required to live with their employers in order to qualify for permanent resident status (see Canadian Citizenship). The reformed Caregiver Program aimed to make caregivers less vulnerable in the workplace and increase their opportunities for better jobs and higher salaries. Individuals are nevertheless required to complete 24 months of full-time work before applying for permanent resident status, and their work permit remains tied to a particular employer.

Key Terms

Emigration The act of leaving one’s region or country of origin to settle in another (see Emigration).

Immigrant A person who settles in a new country (see Immigration to Canada).

Migrant A person who is residing outside their country of origin or who moves from one place to another. Increasingly, migrant and immigrant are being used interchangeable to reflect the complexity of human migration.

Permanent Resident A person who has been granted permanent resident status, which allows them to live and work in Canada. A permanent resident is not a Canadian citizen (see Canadian Citizenship).

Temporary Resident A person who has permission to temporarily enter a country. In Canada, this term is applied to foreign nationals, including students, visitors and participants of the International Mobility Program and Temporary Foreign Worker Program (see Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Programs).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom