Confederation refers to the process of federal union in which the British North American colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada joined together to form the Dominion of Canada. The term Confederation also stands for 1 July 1867, the date of the creation of the Dominion. (See also Canada Day.) Before Confederation, British North America also included Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, and the vast territories of Rupert’s Land (the private domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company) and the North-Western Territory. Beginning in 1864, colonial politicians (now known as the Fathers of Confederation) met and negotiated the terms of Confederation at conferences in Charlottetown, Quebec City and London, England. Their work resulted in the British North America Act, Canada’s Constitution. It was passed by the British Parliament. At its creation in 1867, the Dominion of Canada included four provinces: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario. Between then and 1999, six more provinces and three territories joined Confederation.

This is the full-length entry about Confederation. For a plain language summary, please see Confederation (Plain Language Summary).

Background: Early Proposals for Federation

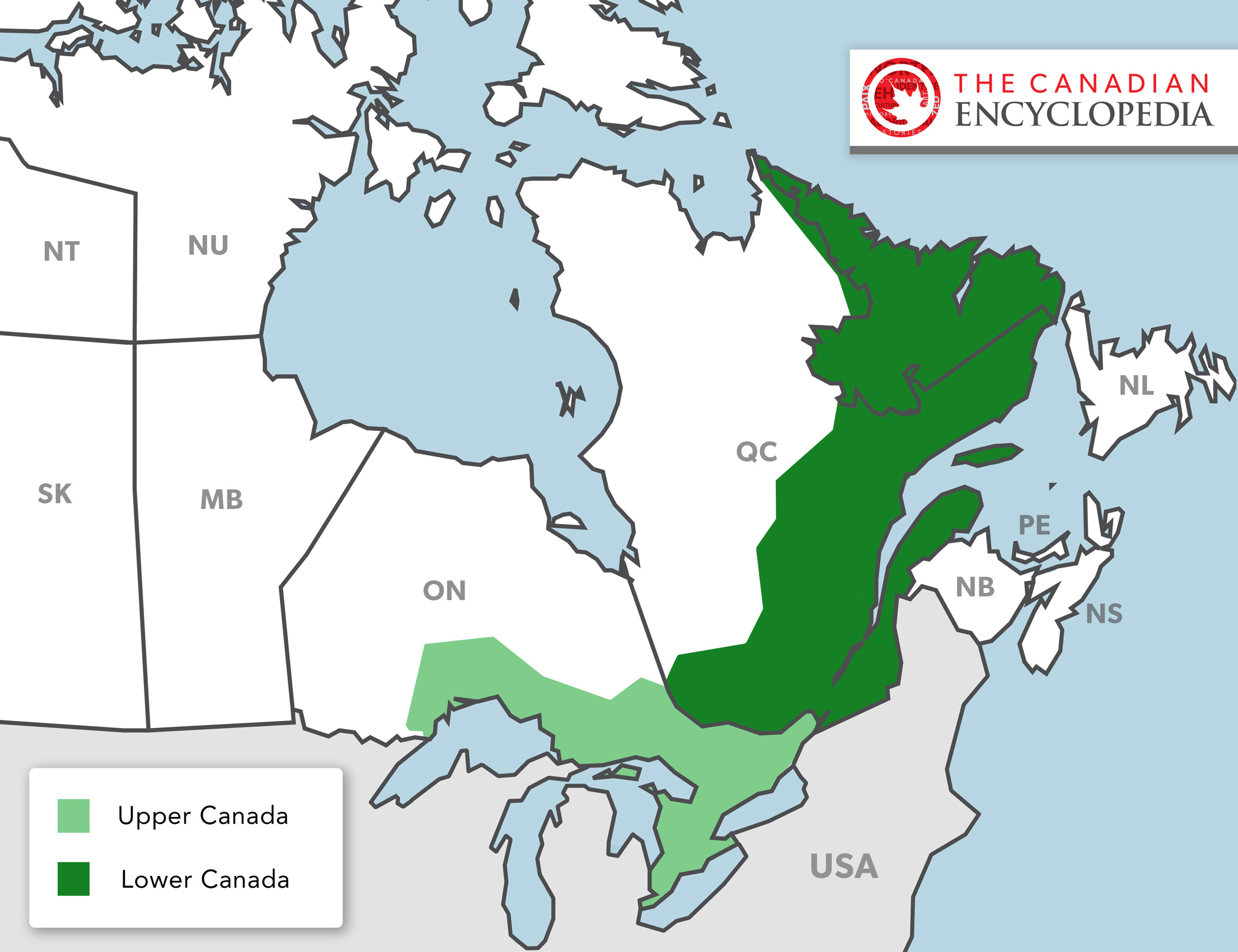

According to historian P.B. Waite, “Confederation appeared in Canada in fits and starts.” The union of the British North American colonies was an idea Lord Durham discussed in his 1839 Report on the Affairs of British North America. The Durham Report, as it came to be known, called for the union of Upper and Lower Canada. This was achieved in 1841 following the Act of Union. Upper and Lower Canada were renamed Canada West and Canada East, respectively. They were governed by a single legislature as the Province of Canada.

In 1849, the Montreal-based Annexation Association called for the annexation of the Province of Canada by the United States. In response to this, the British American League, a Tory association, called for a study of a union of the British North American colonies. Between 1856 and 1859, union was discussed with some frequency in newspapers and in Canada’s legislature. It was usually proposed as a remedy for a political or economic crisis.

The call for a federation of BNA colonies was first issued by Amor de Cosmos. The British Columbia politician and newspaper publisher made the call in the first issue of The British Colonist in 1858. That same year, politicians from Canada East and West — Alexander Galt, George-Étienne Cartier and John Ross — proposed a federation of BNA colonies to the Colonial Office in England. It was received with “polite indifference.”

Reasons for Confederation

Negotiations for the union of British North America gained traction in the 1860s. By that time, Confederation had been a long-simmering idea. Confederation was inspired in part by fears that British North America would be dominated and even annexed by the United States. (See also: Manifest Destiny.) These fears grew following the American Civil War (1861–65).

The violence and chaos of the Civil War shocked many in British North America. They saw the war as partly the result of a weak central government in the US. This inspired ideas about the need for a strong central government among the BNA colonies. (See also: Federalism.) Many in the BNA colonies also believed that Britain was increasingly reluctant to defend them against possible American aggression.

After winning the war, the American North was left with a large and powerful army. There was talk in US newspapers of invading and annexing Canada. This would have been done to avenge Britain’s collaboration with the American South during the war. Several US politicians also favoured annexing Rupert’s Land. The vast northwestern territory represented a third of what would become Canada. Fears of American expansionism only increased after the US purchased Alaska in 1867.

After the Civil War, anger at British support for the American South also led the US to cancel the reciprocity treaty. It had allowed free trade on many items between the US and British North America. Suddenly, Confederation offered the BNA colonies a chance to create a new free-trade market.

The idea of uniting the BNA colonies into a single country was fueled by several key factors: a protectionist US trade policy; fears of American aggression and expansion; and Britain’s increasing reluctance to pay for the defence of British North America. Confederation offered Britain an honourable way to ease its economic and military burden in North America. It would also give its BNA colonies strength through unity.

The Dominion of Canada wasn’t born out of revolution, or a sweeping outburst of nationalism. Rather, it was created in a series of conferences and orderly negotiations. These culminated in the terms of Confederation on 1 July 1867. The union of the British North American colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada (what is now Ontario and Quebec) was the first step in a slow but steady nation-building exercise. It would come to encompass other territories and provinces. It eventually fulfilled the dream of a country “from sea to sea” — A Mari usque ad Mare (Canada’s motto).

(See also: Confederation Timeline; Confederation Collection; Constitution Act, 1867; Editorial: Confederation, 1867; Fathers of Confederation; Mothers of Confederation; Confederation’s Opponents.)

Maritime Union

By 1864, Confederation had become a serious issue in the Province of Canada (formerly Lower Canada and Upper Canada). In the Atlantic colonies, however, a great deal of pressure would still be needed.

A series of fortuitous events helped. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick had been divided in 1784. There was interest in both regions in reuniting. They were helped by the British Colonial Office. It felt that a political union of all three Maritime colonies, including Prince Edward Island, was desirable. Maritime union would abolish three colonial legislatures and replace them with one.

In the spring of 1864, all three legislatures declared an interest in having a conference on the subject. But nothing was done. Once the Province of Canada announced an interest in attending such a meeting, the Maritime governments began to organize. Charlottetown was appointed as the place — PEI officials would not attend otherwise — and 1 September 1864 was chosen as the date. (See also: Charlottetown Conference.)

Political Deadlock in the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada was growing more prosperous and populous. It was rapidly developing politically, socially and industrially. As it did, its internal rivalries also grew. As a result, the job of governing Canada West (now Ontario) and Canada East (now Quebec) from a single legislature became difficult. (See also: Act of Union.)

After achieving responsible government, politicians in Canada West began calling for true representation by population. In the 1840s, Canada West benefitted from having a disproportionately large number of seats in the legislature. (It had a smaller population than Canada East, but the same number of seats.) By the 1850s, the population of Canada West was the bigger of the two. Reformers then supported the campaign for “rep by pop.” This would mean more seats for the West.

This and other divisive issues — such as government funding for Catholic schools throughout the colony — made English Protestants in Canada West suspicious of French Catholic power in Canada East. By 1859, the rift between English and French had created years of unstable government and political deadlock. It was worsened by a growing divide between conservatives and reformers within Canada West. This made solving the colony’s needs and problems nearly impossible. Structural change was required to break the political paralysis. Confederation would separate the two Canadas and give each its own legislature. This was posed as the solution to these problems.

George Brown's reformers described themselves as "no dirt, clear grit all the way through.

The Great Coalition of 1864

By 1864, four short-lived governments had fought to stay in power in the Province of Canada. Canada West’s two principal groups — the Conservatives (led by John A. Macdonald) and Clear Grits (led by George Brown) — formed an alliance. It was known as the Great Coalition. It sought a union with the Atlantic colonies. Three of the Province of Canada’s four major political groups supported the coalition. This gave Confederation a driving force that it never lost. It allowed Confederation to proceed with support from British North America’s most populous region.

In Canada East, Confederation was opposed by A.A. Dorion’s Parti rouge. But it was supported by the dominant political group, the conservative Parti bleu. The Parti bleu was led by George-Étienne Cartier, Hector Langevin and Alexander Galt. By 1867, they had the necessary support of the Catholic Church. Confederation was justified on the grounds that French Canadians would get back their provincial identity. Their capital would once more be Quebec City. French Canadians feared anglophone domination of government. But Confederation would grant French Canadians their own legislature and a strong presence in the federal Cabinet. Of all the proposed changes, Confederation was the least undesirable for French Canadians.

Charlottetown Conference

The “Canadians” sailed to the Charlottetown Conference on 29 August 1864. They travelled aboard the Canadian government steamer SS Queen Victoria. The conference was already underway. Discussions for Maritime union were not making much progress. The Canadians were invited to submit their own proposals for a union of the BNA colonies. The idea of a united country quickly took over. (See also: The Charlottetown Conference of 1864: The Persuasive Power of Champagne.)

Quebec Conference

A month later, the colonies called a second meeting to discuss Confederation. At the Quebec Conference, the delegates passed 72 Resolutions. These explicitly laid out the fundamental decisions made at Charlottetown, including a constitutional framework for a new country. The Resolutions were legalistic and contractual in tone. They were deliberately different from the revolutionary tone of the American Constitution, which had been drafted a century earlier. (See also: Quebec Conference of 1864; Constitutional History.)

The Canadian Resolutions outlined the concept of federalism. Powers and responsibilities would be divided between the provinces and the federal government. (See also: Distribution of Powers.) Cartier pushed hard for provincial powers and rights. Macdonald was keen to avoid the mistakes that had led to the US Civil War. He advocated for a strong central government. A semblance of balance was reached between these two ideas.

The Resolutions also outlined the shape of a national Parliament. There would be an elected House of Commons based on representation by population, and an appointed Senate. Its seats would be equally split between Canada West, Canada East and the Atlantic colonies. Each region would have an equal voice in the appointed chamber.

The resolutions also included specific financial commitments. These included the construction by the new federal government of the Intercolonial Railway from Quebec to the Maritimes. The colonies recognized they needed to improve communications and grow economically. Railways between the colonies would boost economic opportunity through increased trade. They would also make borders more defensible by enabling the quick movement of troops and weaponry. This was important, as the memory of the US invasion of British North America during the War of 1812 was still fresh. (See also: Railway History.)

Some Maritime delegates declared that the building of a rail line was a precondition of their joining Canada. This key undertaking secured the inclusion of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in Confederation.

Atlantic Canada and Confederation

The Atlantic colonies of Newfoundland, PEI, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were more satisfied with the status quo than Canada West. All except Newfoundland enjoyed prosperous economies. They felt comfortable as they were. The bulk of the population, especially in Nova Scotia and PEI, saw no reason to change their constitution just because Canada had outgrown its own.

Even Newfoundland, despite economic difficulties in the 1860s, postponed a decision on Confederation in 1865. In an election in 1869, they decisively rejected it. (See also: Newfoundland and Labrador and Confederation.)

The more prosperous PEI resisted almost from the start. A small, dedicated group of Confederationists made little headway until early in the 1870s. At that time, PEI was badly indebted by the construction of a railway. It joined Confederation in 1873 in return for Canada taking over its loan payments. (See also: PEI and Confederation.)

Nova Scotians were divided. Confederation was popular in the northern areas of the mainland and in Cape Breton. But along the south shore and in the Annapolis Valley — the prosperous world of shipping, shipbuilding, potatoes and apples — the idea seemed unattractive or even dangerous.

Conservative Premier Charles Tupper was ambitious, aggressive and confident. He went ahead with Confederation anyway. He was convinced that in the long run it would be best for Nova Scotia, and perhaps also for himself. (Tupper briefly served as prime minister in 1896.) His government was not up for re-election after Confederation was finalized. By that time, it was too late for the 65 per cent of Nova Scotians who opposed the idea. (See also: Nova Scotia and Confederation; Repeal Movement.)

New Brunswick was only a little more enthusiastic. In 1865, the anti-Confederation government of A.J. Smith was elected. (See: Confederation’s Opponents.) It collapsed the following year. It was replaced by a new pro-Confederation government.

Its support for a British North American union was helped by the Fenian invasions of that spring. The raids badly weakened anti-Confederation positions. They revealed shortfalls in the leadership, structure and training of the Canadian militia. This led to a number of reforms and improvements. More importantly, the threat the irregular Fenian armies posed to British North America led to greater support among British and Canadian officials for Confederation. Growing concerns over American military and economic might had the same effect. (See also: New Brunswick and Confederation; Fenian Raids; Thomas D’Arcy McGee.)

Indigenous Peoples and Confederation

Indigenous peoples were not invited to or represented at the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences. This despite the fact they had established what they believed to be bilateral (nation-to-nation) relationships and commitments with the Crown through historic treaties. (See also: Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada; Royal Proclamation of 1763.) The Fathers of Confederation, however, held dismissive, paternalistic views of Indigenous peoples. As a result, Canada’s first peoples were excluded from formal discussions about unifying the country.

Confederation had a significant impact on Indigenous communities. In 1867, the federal government assumed responsibility over Indigenous affairs from the colonies. With the purchase of Rupert’s Land in 1870, the Dominion of Canada extended its influence over the Indigenous peoples living in that region. The Dominion wanted to develop, settle and claim these lands, as well as those in the surrounding area.

From 1871 to 1921, the federal government signed a series of 11 treaties (the “numbered treaties”) with various Indigenous peoples. The government promised them money, certain rights to the land and other concessions. In exchange, the First Nations in all colonies except British Columbia ceded (surrendered) their traditional territories.

Most of the promises in these treaties went unfulfilled. The intentions expressed by the treaties, and the clarity with which they were communicated to and understood by the Indigenous people who signed them, has been the subject of considerable debate. The decades following Confederation saw the government increasingly try to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society. (See also: Potlatch Ban; Residential Schools; Sixties Scoop.)

DID YOU KNOW?

In contrast to the rest of the country, British Columbia exists almost entirely on unceded territory. Instead of signing treaties with Indigenous peoples, BC governor James Douglas issued a proclamation in 1859 claiming all land and resources in BC as the property of the Crown. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that land title not formally ceded by treaty rests with the area’s Indigenous peoples.

(See also: Indian Act; Reserves.)

London Conference

British Colonial Secretary Edward Cardwell was a strong supporter of Confederation. He felt that the cost of defending the BNA colonies against potential US aggression was too high. He vigorously instructed his governors in North America to promote the idea, which they did. Confederation meant Canada would have to pay for its own defence, rather than relying on British support.

The London Conference (December 1866 to February 1867), was the final stage of translating the 72 Resolutions of 1864 into legislation. The result was the British North America Act, 1867 (now the Constitution Act, 1867). It was passed by the British Parliament and was signed by Queen Victoria on 29 March 1867. It was proclaimed into law on 1 July 1867. (See: Canada Day.)

The Dominion Grows

British policy favouring the union of British North America continued under Cardwell’s successors. The Hudson’s Bay Company sold Rupert’s Land to Canada in 1870. The young country expanded with the addition of Manitoba and the North-West Territories that same year. British Columbia was brought into Confederation in 1871 and PEI in 1873.

The Yukon territory was created in 1898 and the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905. Having rejected Confederation in 1869, Newfoundland and Labrador finally joined in 1949. In 1999, Nunavut, meaning “our land” in Inuktitut, was carved out of the Northwest Territories. This was part of the largest Indigenous land claim settlement in Canadian history.

(See also: Newfoundland Bill; Newfoundland Joins Canada; Newfoundland and Labrador and Confederation; Nunavut and Confederation; Comprehensive Land Claims: Modern Treaties.)

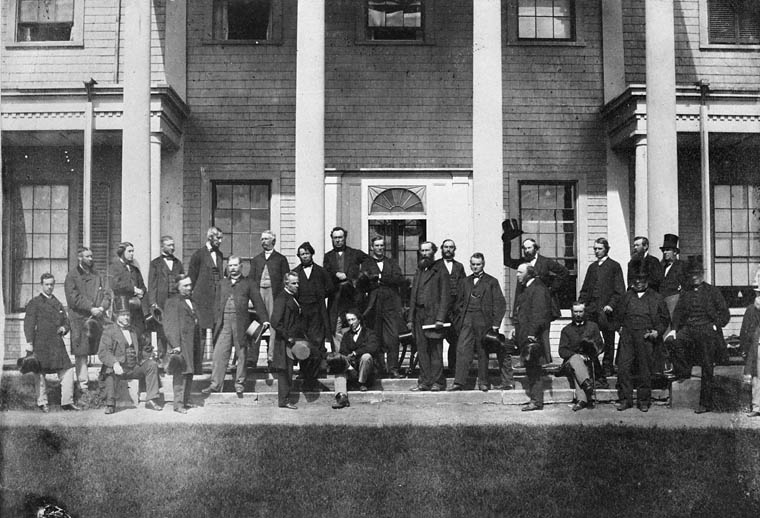

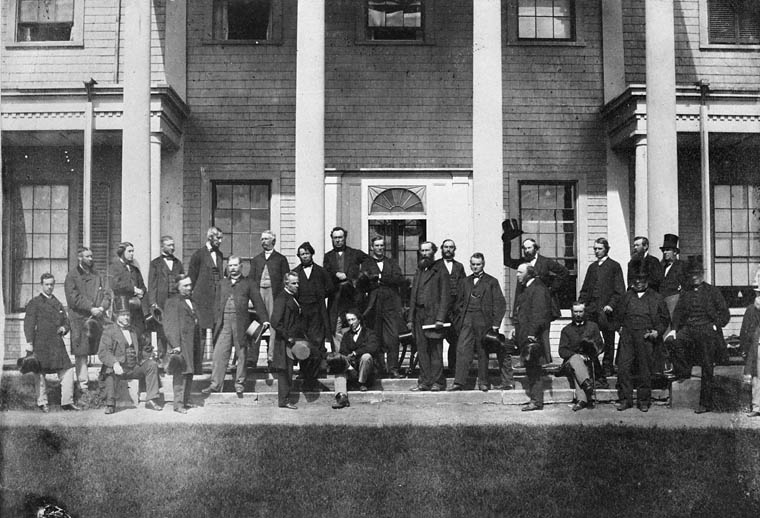

Fathers of Confederation

Confederation was the product of three conferences attended by delegates from five colonies. Thirty-six men are traditionally regarded as the Fathers of Confederation. They represented the BNA colonies at one or more of the conferences that led to Confederation.

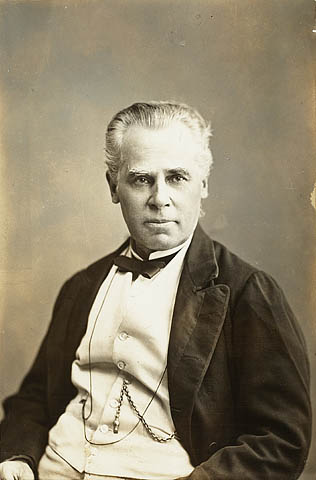

Among the Fathers of Confederation, several played especially significant roles. The project of Confederation likely would not have been undertaken were it not for the dogged persistence of George Brown. Sir George-Étienne Cartier was a key driving force who insisted on certain essential provincial rights. Sir John A. Macdonald orchestrated the political machinations necessary to get all the various parties to sign on. And Alexander Galt also made important contributions.

The subject of who should be included among the Fathers of Confederation has been a matter of some debate. The definition can be expanded to include those who were instrumental in bringing Manitoba ( Louis Riel), British Columbia (Amor de Cosmos), Newfoundland and Labrador ( Joey Smallwood) and Nunavut (Tagak Curley) into Confederation. (See also: Fathers of Confederation Table; George Brown: 1865 Speech in Favour of Confederation.)

Mothers of Confederation

The wives and daughters of the original 36 men have also been described as the Mothers of Confederation. They played key roles in the social gatherings that were a vital part of the Charlottetown, Quebec and London Conferences. Official records of the 1864 Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences are sparse. But historians have been able to flesh out the social and political dynamics at play through the letters and journals of: Anne Brown, spouse of George Brown; Mercy Coles, daughter of PEI Premier George Coles; and Agnes Macdonald, wife of Sir John A. Macdonald. They provide a view into the experiences of privileged women of the era. They also draw attention to the contributions those women made to the historic record and political landscape.

Mercy Coles’ diary, Reminiscences of Canada in 1864, is one of the most detailed sources about the events that preceded Confederation. The diary includes descriptions of the Fathers of Confederation and their personalities. It brings to light the social politics of mid-19th-century Canada.

“Lady Macdonald in the gallery, like the Queen of the day, stamped her foot and exclaimed ‘Did ever any person see such tactics!’” c. 1878.

A Country in 13 Parts

| Province or Territory | Joined Confederation |

| Alberta | 1905 |

| British Columbia | 1871 |

| Manitoba | 1870 |

| New Brunswick | 1867 |

| Newfoundland | 1949 |

| Northwest Territories | 1870 |

| Nova Scotia | 1867 |

| Nunavut | 1999 |

| Ontario | 1867 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1873 |

| Quebec | 1867 |

| Saskatchewan | 1905 |

| Yukon | 1898 |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom