Canadians use computers in many aspects of their daily lives. Eighty-four per cent of Canadian families have a computer in the home, and many people rely on these devices for work and education. Nearly everyone under the age of 45 uses a computer every day, including mobile phones that are as capable as a laptop or tablet computer. With the widespread use of networked computers facilitated by the Internet, Canadians can purchase products, do their banking, make reservations, share and consume media, communicate and perform many other tasks online. Advancements in computer technologies such as cloud computing, social media, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things are having a significant impact on Canadian society. While these and other uses of computers offer many benefits, they also present societal challenges related to Internet connectivity, the digital divide, privacy and crime.

History of Computers in Canada

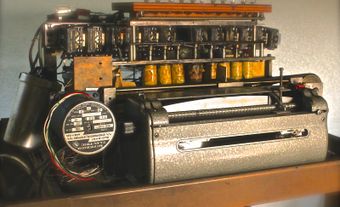

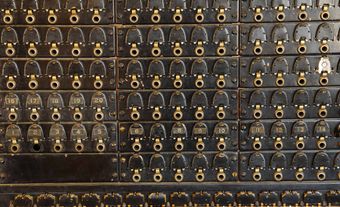

The first electronic computers in Canada were built in the years following the Second World War. They had limited, specialized uses for governments and universities. Businesses began to use these machines to computerize their records in the mid- to late 1950s. Around 1964, the first computer science departments appeared at Canadian universities. However, it wasn’t until the introduction of the personal computer (PC) to small businesses, homes and schools in the 1980s that these machines began to have broad social implications.

Personal computers were smaller, less expensive and more user-friendly than the mainframe computers favoured by large organizations. They were sold with a display, keyboard, mouse, memory and, after 1983, hard drives, much the way PCs are today. They could run software such as word processors, drawing programs and games.

Unemployment in Canada reached a historical peak of 13.1 per cent in December 1982. Economists began to recognize the need for more training programs in the emerging computer field. The introduction of computers into public schools, where they had been rare, began in earnest during this decade. The involvement of provincial departments or ministries of education ranged from initiating local projects to commissioning custom hardware and software.

Did you know?

In the 1940s and 1950s, programming was considered a good job for women. They played important roles in codebreaking on the Enigma project in the UK, calculating ballistics trajectories using the ENIAC (the first programmable digital computer in the United States) and computing flight paths for NASA. Today, only 25 per cent of students enrolled in university-level computer science and math programs in Canada are women. This decline can be traced to the appearance of PCs in the home: they were marketed as toys, and families were more likely to buy them for boys.

By 1989, approximately one-third of Canadian workers used computers as part of their work, and 19.4 per cent of the population had a computer at home. Computers were more common in urban areas than in rural ones, where only 13.9 per cent of households had PCs. In rural areas and small towns, computers were also more common among individuals with higher education and households with higher total income. Over the years, federal and provincial governments have implemented policies aimed at reducing these and other disparities in access that constitute the “digital divide” in society. While the income-based divide has narrowed in Canada in the 21st century, it remains more pronounced than the divide across education levels (see also Income Distribution).

In 2017, 84.1 per cent of Canadian households had a home computer and 89 per cent had Internet access from home.

Internet Connectivity in Canada

A good network connection is essential to using a computer to access the wealth of information and services available on the Internet. Canadian homes connect to the Internet via broadband technologies including cable, digital subscriber loop (telephone lines) and satellite. A small fraction of households (2 per cent as of 2017) use much slower dial-up connections. Mobile devices send and receive data using cellular and satellite technologies. Internet connectivity in rural areas tends to be slower and cost more, when it is available. Many remote communities depend on expensive satellite connections. (See also Satellite Communications.)

In December 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) declared that Internet access is a basic or essential service for Canadians. Making high-speed Internet connectivity available across the country, including in rural areas, has since been a priority of the CRTC. To this end, the agency has set targets for the private sector and created a fund for infrastructure development.

Net Neutrality in Canada

An ongoing issue before the CRTC is net neutrality, the principle by which all data transmitted over the Internet is treated as equal. Current CRTC policies support net neutrality. However, Internet service providers (ISPs) are arguing for the ability to offer users the option of paying more for priority access to their network’s data transfer capacity, called bandwidth. This would allow ISPs to sell new products (e.g., subscriptions to high-speed streams of sports).

On one hand, net neutrality is desirable because it prevents private companies from making policy decisions about access. For instance, without neutrality rules, an ISP could block access to sites that are critical of the company. On the other hand, preferential treatment of some data is necessary to guarantee quality of service or public safety. For example, it is more important for data in a video stream to arrive without delay than it is for data in an email message. In the case of data crucial to the operation of remote medical procedures or self-driving cars, the priority is even greater.

Digital Divide in Canada

The digital divide is the gap between Canadians who have access to computers (including the Internet) and those who do not. In a 2012 study, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that approximately 25 per cent of Canadians ages 16–65 lacked digital literacy skills. Lack of access seriously limits one’s ability to participate in Canadian life as a worker, consumer and citizen. There are several barriers that keep some members of society on the have-not side of the divide, and many Canadians face more than one of these barriers.

Geography is one barrier. Approximately 18 per cent of Canadians, typically located in rural communities or sparsely populated areas, do not have access to affordable high-speed Internet. This is especially pronounced in the North. As of 2017, Internet faster than 5 megabits per second (the speed recommended for streaming high-definition video) was available to only 29.9 per cent of households in Nunavut, and this figure refers to ISP coverage rather than user subscriptions. Wireless high-speed Internet is available across the territory at speeds fast enough to stream standard definition video, but the cost per month is $399. A comparable wired broadband service in Ontario would cost $35 per month.

Individuals who have less money find it more difficult to purchase computers and pay for network connectivity. In 2012, Statistics Canada reported that nearly every high-income home had Internet access, compared to 58 per cent of low-income households. Lower income on its own may not be a barrier, as some people use computers at a public library or connect to free Wi-Fi (wireless) networks using a mobile phone. However, other factors, such as lack of mentors, role models and training opportunities disproportionately affect those with low income.

The digital divide during the COVID-19 pandemic

The 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic highlighted the digital divide in Canada. Canadians stayed isolated at home for weeks to limit the virus’ spread. Many non-essential businesses and services remained closed. The Internet became an even more essential tool during this time. Many relied on it to continue their work or education. Access to certain goods and services moved mostly online. Public health officials urged Canadians to connect virtually with family and friends. But the limited options for those without home Internet heightened the social and economic barriers they faced. Groups such as OpenMedia and ACORN Canada called for governments to treat Internet access a basic right. They argued that the pandemic showed the urgent need for such a policy.

Individuals with high levels of education are more likely to have Internet access than those without. However, 99 per cent of current students in Canada have access to the Internet, which is higher than any other segment of the population by level of educational attainment, including university graduates.

Language is another major barrier to digital literacy in Canada. Worldwide, 54 per cent of the pages on the Internet are in English, but only 4 per cent are in French and a negligible percentage are in an Indigenous language. Federal government websites are available in both official languages, but provincial and municipal sites vary by region.

Finally, age is another factor in the digital divide. Senior citizens tend to use computers less than any other age group. Between 2013 and 2016, however, there was a significant increase in usage rates among older Canadians.

Privacy Regulations in Canada

Information privacy is the ability to control one’s own information by selecting who can access it and when. In Canada, there are regulations on the handling of personal information by governments, institutions and companies. Personal information means details about an individual, including name, address, age, education, medical or employment history, personal views and opinions, and identifying numbers (e.g., Social Insurance Number, driver’s license number and health card number).

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) oversees two federal privacy laws. The Privacy Act governs how federal government departments and agencies handle personal information. The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) governs the way many businesses handle personal information. Under these laws, individuals have several privacy protections, including the right to consent, accuracy and open communication from businesses. If one feels that their privacy rights have been violated, they can make a complaint to the OPC.

At the provincial level, there are additional laws, regulators and remediation mechanisms. Every Canadian province and territory has a privacy commissioner or ombudsperson who oversees privacy legislation in their jurisdiction.

Privacy Concerns in Canada

Although Canadians have privacy rights, it can be difficult for users of online services to safeguard their privacy according to their preferences. The terms of use and privacy policies for websites, search engines and social media platforms require users to consent to the collection and sharing of personal information. Sharing details of this kind allows advertisements to be targeted to individual users.

Online privacy is still evolving and there are some issues that are still to be resolved. One is the right to request that one’s information be corrected by private corporations. This right is already protected by PIPEDA, but the federal Privacy Commission brought a case before the Federal Court in September 2018 to clarify whether it applies to Google search results for a person’s name.

The existing privacy law set out in PIPEDA does not apply to political parties, not-for-profit organizations and charities. This means such groups do not require individuals’ consent to collect personal information, and they are not required to disclose what information they have. The Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario has recommended that, to limit ethical and security risks, privacy laws be extended to cover political parties in the province.

(See also Few Companies Prepared for New Privacy Law; Breaches of Personal Privacy Are Growing.)

Cloud Computing

Cloud computing is the practice of using software and hardware that is hosted remotely on servers and in data centres connected to the Internet rather than on personal or local computers. Commonly used cloud applications include office productivity software (e.g., word processing and spreadsheet applications), computer backups and file sharing. The shift to cloud computing, which was well underway by the first decade of the 21st century, has changed how people access and pay for software, how easy it is to create websites and how people control their data.

With cloud computing, users no longer need to purchase software and install it on their computers. Instead, they access the software through a web browser and pay for it through subscriptions or by watching advertisements. The advertisements are typically selected for display using data about users’ browsing habits. Although the ad-funded model of cloud computing could help bridge the digital divide by eliminating subscription fees, some argue that it is intrusive and cite concerns about the security of the data collected. Moreover, use of cloud software depends on having a reliable and fast Internet connection, a barrier that can deepen the digital divide.

Hardware in the cloud has made it easier to put content on the web, to create interactive websites, and to open online stores. Content creators can access tools on the web and publish their content to a sharing platform (e.g., SoundCloud for audio files). Software developers can deploy servers in minutes, using a few clicks inside a web browser to make their applications available to users. Sellers can go to an e-commerce platform provider such as Shopify and open a store in just a few hours.

Cloud Computing and Privacy

There are privacy concerns about where users’ files are stored and how service providers use their data. Files such as word-processor documents, drawings and computer source code are stored on servers in the cloud. Service providers also have data about when users log in, how they connect, their Internet Protocol (IP) address and other usage details. Privacy legislation requires businesses to limit who has access to user data. But there are privacy risks from service providers’ employees, hackers, law enforcement officers (who can request data without a warrant) and intelligence agencies.

Cloud computing providers can take a variety of measures to ensure that they comply with privacy legislation. One common action is to store the data in Canada. This may not fully protect the information, however, as a foreign-owned data centre located in Canada may still be subject to disclosure to foreign governments.

Did you know?

A data centre uses a lot of electricity to power its computers and cool its space. Data centres are therefore sometimes located near electric-generating stations or hydroelectric dams. Quebec has the lowest electricity prices in the country, making it an attractive site for international cloud computing providers to establish a Canadian data centre. All the major cloud service providers (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform and IBM Cloud) have a data centre in the province. The economic benefit to Quebec of these data centres was estimated at $117 million in 2015 and is projected to grow to more than $600 million annually by 2025.

Despite these concerns, Ontario’s Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade has noted that small businesses may receive greater privacy protections from good cloud service providers than they are able to implement themselves.

Social Media

Traditional media such as print, television and radio are one-way communication channels from producers to consumers. By contrast, social media are multi-way communication channels that allow users to be both producers and consumers on a website or computer application. Social media include discussion forums (e.g., reddit), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook and LinkedIn), reference materials (e.g., Wikipedia and wikiHow), and content sharing sites (e.g., YouTube and Google Docs).

According to a 2017 report by Ryerson University’s Social Media Lab, the three most popular social media platforms in Canada are Facebook, YouTube and LinkedIn. Facebook is used primarily for connecting with other people, groups and events. Despite the common belief that Facebook is used by older people, 95 per cent of young adults ages 18–24 have Facebook accounts. YouTube is a platform for publishing, watching, sharing and commenting on videos. LinkedIn is similar to Facebook, but with a focus on work relationships and career building.

Traditional media and social media are now interdependent. Not only do social media users share news articles from traditional media with their contacts, but traditional media also report on social media as a source of news. Politicians even use Twitter, a microblogging platform, to make policy announcements. (See also Media Convergence.)

Concerns about Social Media

In 2017, 26 per cent of males and 38 per cent of females in grades 9–12 in Canada’s largest school board (the Toronto District School Board) reported using social media almost constantly. The same study found that students were more worried and had lower emotional well-being than in previous years. Reasons underlying this relationship between social media use and mental health effects include more time alone and less emotional connection with others.

Other concerns with social media networks include the potential for political campaigns to interfere with democratic processes by circulating false or biased information (e.g., “fake news” and propaganda). In 2017, Facebook admitted that a company linked to the Russian government had purchased thousands of divisive ads intended to influence the 2016 United States presidential election. Politicians and journalists have warned that similar social media campaigns could target a Canadian election.

Privacy is also an issue with these networks, given the amount of data they hold about their users. In 2018, Canadian whistleblower Christopher Wylie revealed that British political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had collected data from millions of Facebook profiles and used it in various political campaigns in the United States, the United Kingdom and Mexico. The privacy commissioners of Canada and British Columbia subsequently investigated whether Facebook had violated Canadian privacy laws. In 2019, they concluded that Facebook had “committed serious contraventions” of these laws and “failed to take responsibility for protecting the personal information of Canadians.”

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capacity of a machine, such as a computer, to interpret input from its environment and learn, make decisions or solve problems. Data mining and machine learning are examples of AI. Handing over decision making to machines leads to a host of questions regarding responsibility, legality and public safety. Two technologies among many that raise these issues are self-driving cars and facial recognition.

Self-Driving Cars

Self-driving cars will be able to move along streets and highways with or without a human in the driver’s seat. They will be able to sense the state of the environment, including other moving vehicles, and choose an appropriate course and speed. Early versions of the technology, such as collision avoidance and guidance to stay in a lane, are already available in mass-market vehicles.

Self-driving cars are generally not legal in Canada. The exception is Ontario, which started a pilot project in 2016 to allow autonomous cars to be tested on roadways and highways. These cars must have a licensed motorist in the driver’s seat who is ready to take control of the car in certain circumstances.

According to current laws, which apply to traditional vehicles, the driver is responsible for complying with the law. In the case of driverless cars, there is no legal mechanism for sharing the responsibility. There is also no mechanism for certifying that a self-driving car is safe enough for general use.

Facial Recognition

Facial recognition is a computer’s ability to recognize a person from a still image or video. A common example is Apple’s iPhone X, which can use facial recognition to unlock the phone. The Primary Inspection Kiosks that the Canada Border Services Agency has introduced at major airports across the country are also equipped with facial recognition. These machines take a photo of a traveller and compare it with their passport photo. This same technology can be used to collect data on shoppers at a mall or to track people moving through public spaces. The Calgary Police Service has software that will search a database of 300,000 mug shots for a match to an image from a video or photograph.

Did you know?

Some units of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) used facial recognition software called Clearview AI to investigate crimes. Clearview AI was designed to find details about a person in a photo by scanning a database of billions of images collected from social media and other sites. Before Clearview AI’s client list was hacked and leaked to the media in early 2020, the RCMP had denied using facial recognition. Other police forces in Canada also admitted to having used the software following the leak. Amid concerns about privacy, the RCMP said it would only use the software in urgent cases, such as identifying victims of child sexual abuse. The RCMP stopped using Clearview AI once the company ceased operations in Canada in July 2020. A June 2021 report released by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) found that the RCMP had violated the Privacy Act by using Clearview AI.

Critics of facial recognition technologies argue that storing images and personal information violates people’s privacy. Given the legal grey zone of some of these forms of data collection, decisions on when to share data are often made on a case-by-case basis. One such case was the riot that erupted in Vancouver after the Canucks lost the Stanley Cup final in 2011. The Insurance Corporation of BC (ICBC) offered its database of driver’s licence photos to the Vancouver Police Department to help identify suspects in videos and photos using facial recognition software. The police declined, however, as the BC Information and Privacy Commissioner ruled that such a disclosure would require a court order.

Finally, the accuracy of facial recognition software can vary according to race and gender. In 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union conducted an experiment where it tried to match photographs of politicians with mug shots using commercial facial recognition software. The overall inaccuracy rate was only 5 per cent, but persons of colour were twice as likely to be matched incorrectly. Artificial intelligence algorithms can make mistakes in the real world when their creators train them using biased data. (See also Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada.)

Internet of Things

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to “smart” devices or appliances that can connect, exchange data and work together. Some cars, doorbells, thermostats and refrigerators, among other devices, are now sold with these capabilities.

Smart home devices can offer extra security and convenience, such as doorbells with built-in video cameras and thermostats that can be adjusted remotely. By the same token, they can present security risks when hacked or used to invade someone’s privacy. They may also be difficult to maintain; a smart refrigerator can keep a shopping list but is nearly impossible to repair due to a shortage of qualified technicians.

Cities also make use of the IoT. For example, Toronto has responsive traffic signals: the timing of signal cycles changes in response to congestion.

Did you know?

In the late 2010s, Toronto was the planned site of the world’s first smart neighbourhood. The development, called Quayside, would have been “built from the Internet up.” It would have used innovations in infrastructure design, transportation and accessibility. However, critics were concerned about who would own the data collected there through many devices and sensors. The stakes were especially high because Quayside would have set a precedent for similar projects to follow. Sidewalk Labs, which is owned by the same company as Google, withdrew its proposal during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. It said that uncertain economic conditions had made Quayside less financially viable.

Cybercrime in Canada

Widespread use of the Internet has given rise to increases in crime in the following areas: information theft, exploitation, harassment and commerce. In 2015, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act came into force, amending the Criminal Code and other laws to help law enforcement agencies investigate cases of Internet child sexual exploitation and organized crime.

The most common crimes on the Internet involve attacks on information belonging to individuals and organizations. Hackers often attack e-commerce sites. Their primary target is credit card numbers, which can be sold or used to defraud other businesses. Secondary targets are usernames and passwords, which can be used to hack other sites. These kinds of attacks highlight the importance of privacy protections such as those in the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), which require private companies to tell people when their data has been stolen.

Individuals are targeted through email phishing scams. These are messages that appear to come from a legitimate sender, such as a bank, and contain a link to a website where the user is asked to enter personal information.

Pedophiles have used the Internet to access and distribute child pornography. Sexual predators have used it to trick potential victims into meeting with them. Predators use social media, email and other online communication tools to this end. There have also been many reported cases of Internet stalking, whereby a person is harassed through these channels. Hate literature and hateful posts against religious and ethnic minorities also abound.

Cyberbullying is a serious problem among youth, with victims experiencing mental health issues, isolation and low self-esteem, sometimes to the point of suicide. British Columbia teenager Amanda Todd died by suicide in 2012 after being cyberbullied for years over a coerced topless photo that her attacker circulated on the Internet. Nova Scotia teen Rehtaeh Parsons died by suicide in 2013 after a video of her sexual assault was circulated over social media. After her death, multiple inquiries were held. A provincial law was introduced to protect children against cyberbullying, but the Nova Scotia Supreme Court struck it down on 2015 on the grounds that it violated the free-speech clause of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. (See also Cyberbullying Is on the Rise.)

Dark Web

The Internet is also used to traffic in restricted goods and services, such as weapons, drugs, hacking and fraud. These transactions typically occur on the dark web, which is a set of servers that exist on the Internet but require special software and passwords. The best-known dark web software is Tor (The Onion Routing project), which allows users to anonymously browse sites. It is common to pay for transactions on the dark web using cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Cryptocurrencies are entirely electronic, have no central administrator and use encryption to ensure the legitimacy of transactions (see Money in Canada). Research published in 2018 found that a significant portion of vendors on the dark website AlphaBay were selling illicit goods from Canada. The site, which was shut down by US authorities in 2017, was also allegedly founded by a Canadian.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom