British Empire Roots

The Commonwealth is a loose, voluntary association of Britain and most of its former colonies. Its members are independent nations, together accounting for about one-quarter of the world's population. Commonwealth members are pledged, according to a 1971 declaration of principles, to consult and co-operate in furthering world peace, social understanding, racial equality and economic development. These principles were reinforced by the Harare declaration in 1991 in favour of democracy, human rights, local governance, the rule of law, equal opportunities and free trade.

The Commonwealth Secretariat, established in 1965, administers programs of co-operation, arranges meetings and provides specialist services to member countries. The British monarch is head of the Commonwealth, a purely symbolic role.

The roots of the Commonwealth are frequently traced back as far as the Durham Report (1839) and to the advent of Responsible Government in the 1840s. By 1867 the British North American provinces, as well as other British colonies in Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, were self-governing with respect to internal affairs. With Confederation in 1867, Canada became the first federation in the British Empire; its size, economic strength and seniority enabled it to become a leader in the widening of colonial autonomy and the transformation of the empire into a commonwealth of equal nations.

First World War

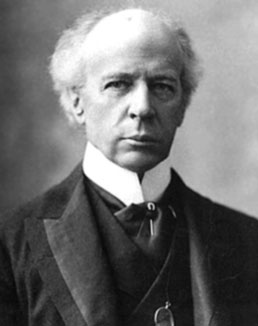

Contingents from all the self-governing British colonies took part in the South African War from 1899 to 1902. Canada sent only volunteers. After the war, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier made it clear at the Colonial and Imperial Conferences in 1902, 1907 and 1911 that participation in imperial defence would always be on Canadian terms.

In 1914 the British king declared war on behalf of the entire empire. The Dominions (a term applied to Canada in 1867 and used from 1907 to 1948 to describe the empire's other self-governing members) decided individually the nature and extent of their participation. They gave generously: more than a million men from the Dominions and 1.5 million from India enlisted in the forces of the empire. There were also huge contributions of food, money and munitions. Although some South African nationalists and many French Canadians opposed participation in a distant British war, the unity of the empire in the First World War was impressive.

Seeking Full Independence

Post-Great War Years

Despite the extent of their First World War commitment, the Dominions at first played no part in setting policy or war strategy. But Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden was especially critical when the war did not go well. When David Lloyd George became British prime minister in late 1916, he immediately convened an Imperial War Conference and created an Imperial War Cabinet, two separate bodies which met in 1917 and 1918.

The War Conference was remembered primarily for Resolution IX, which stated that the Dominions were "autonomous nations of an Imperial Commonwealth" with a "right ... to an adequate voice in foreign policy and in foreign relations." This was chiefly an initiative of Prime Minister Borden, carried at the conference with the help of General Jan Smuts of South Africa. It marked the first official use of the term "Commonwealth."

The Imperial War Cabinet gave leaders from the Dominions and India an opportunity to be informed, consulted and made to feel part of the making of high-level policy. A similar body, the British Empire Delegation, was created at the Paris Peace Conference after the war. Borden and Australian Prime Minister W.M. Hughes also successfully fought for separate Dominion representation at the conference, and for separate signatures on the Treaty of Versailles. Constitutionally, however, the empire was still a single unit: Lloyd George's was the signature that counted. The Dominions, now members of the new League of Nations, remained ambiguous creatures – part nation, part colony, part imperial colleague.

The war pulled each Dominion in different directions. Widespread hopes for greater imperial unity clashed with intensified feelings of national pride and distinctiveness, which resulted from wartime sacrifice and achievement. Borden, a nationalist who wished to enhance Canada's growing international status through commitment to a great empire-commonwealth, tried to reconcile the two impulses. He sought a closely knit commonwealth of equal nations that would consult and act together on the big issues of common concern. Resolution IX had called for a postwar imperial conference to readjust constitutional relations along these lines. It was never held.

1920s

A nationalism quite different from Borden's took control of the Commonwealth in the 1920s. Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was the heir to Laurier's policy of "no commitments." The Chanak Affair and the Halibut Treaty set the tone, and King was a clear winner at the Imperial Conference of 1923. A trend away from imperial diplomatic unity and towards a devolved, autonomous relationship between Britain and the Dominions was established.

King believed that the British connection could be maintained only if it allowed Canadians, particularly the substantial minority of non-British descent, to concentrate on developing a strong North American nation. He was not alone in wishing to emphasize diplomatic autonomy, although the reasons differed. The British had little wish for a co-operative Anglo-Dominion foreign policy that would require the Foreign Office to engage in time-consuming consultation with much smaller powers. South Africa and the Irish Free State, which were granted Dominion status on the Canadian model in 1921, were even more radical than King in pushing for decentralization.

At the Imperial Conference of 1926, South African Prime Minister J.B.M. Hertzog demanded a public declaration that the Dominions were independent states equal in status to Britain and separately entitled to international recognition. King opposed the word "independent," which might conjure up unhappy visions of the American Revolution in pro-British parts of Canada. But King endorsed the thrust of Hertzog's demand. The conference adopted the Balfour Report, which led to the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, establishing the right of the Dominions to full legislative autonomy.

1930s

The Commonwealth of the 1930s was a study in contradiction, a mixture of the national and the imperial, and confusing to outsiders. To some extent Commonwealth countries conducted their own foreign affairs and managed their own defences. Yet a common head of state, common citizenship and substantial common legislation remained. Association with a vast and apparently powerful empire – then at its greatest extent, covering more than 31-million square kilometres – brought the Dominions prestige, prosperity and protection.

The Ottawa Agreements of 1932, although falling far short of creating the self-sufficient unit some had dreamed about, bound Commonwealth countries tighter in an interlocking series of bilateral preferential trading agreements. There was also substantial military co-operation, of enormous benefit to the Dominions' fledgling armed forces.

Newfoundland, proudly "Britain's oldest colony," had long enjoyed Responsible Government, was represented at Colonial and Imperial Conferences, and had fought with distinction in the First World War. However, financial crisis brought about the return of British rule (see Commission of Government) from 1934 to 1949, at which point Newfoundland and Labrador became a province of Canada.

Second World War

Dependence and co-operation did not necessarily lead to commitment, and in peacetime the Dominions were wary of European entanglements. When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Australia and New Zealand did not hesitate to become involved in the Second World War. Canada waited one week before Parliament endorsed the King government's decision to fight. South Africans split on the issue and Prime Minister Hertzog resigned, but the final response was to join the war effort. Only Ireland stayed aloof.

Immense contributions of men and materiel were made, including more than two million troops from the four Dominions, and 2.5 million from India. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, trained 131,553 aircrew, and was a major Canadian contribution. Such efforts were all the more important and valued because the Dominions alone fought at Britain's side from the first day to the last.

However, there was no Imperial War Cabinet this time, no Commonwealth consensus on the need to strengthen ties. British power was waning and Dominion confidence was on the rise, weakening traditional links. Britain's subject peoples in Africa and Asia also looked increasingly to themselves for solutions to their problems.

Commonwealth Grows, Weakens

The "old" Commonwealth, made up of Australia, Canada, Britain, New Zealand and South Africa was often likened to a club. By 1949, a "new" Commonwealth had emerged which was quite different. Ireland left the Commonwealth in 1949. India, which had been lurching towards responsible government and Dominion status for decades, achieved independence in 1947, although at a price: it was divided on religious grounds into the Dominions of India and Pakistan. Neighbouring Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (now Myanmar) achieved independence in 1947-48, with Sri Lanka obtaining Dominion status and choosing Commonwealth membership.

Through the London declaration of 1949, India was allowed to remain in the Commonwealth after declaring itself a republic (without the British monarch as its head of state).

Adopting a formula suggested by then-Canadian diplomat Lester Pearson, the monarch was declared "the symbol of the free association of its member nations, and as such Head of the Commonwealth." The Commonwealth was no longer predominantly white and British; allegiance to a common Crown was no longer a prerequisite of membership, and the concept of common citizenship was fading fast.

There were high hopes for the "multiracial" Commonwealth, which many believed could be a force and example for understanding among nations. A bigger grouping, however, was more difficult to keep together, particularly when members were moving more than ever before in different directions, partly in order to develop responses to a Cold War world dominated by hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Britain itself began the long road to eventual membership (in 1973) in the European Economic Community, to the consternation of much of the older Commonwealth. Canada, Australia and New Zealand looked increasingly to the US as an ally and trading partner. India preached the doctrine of non-alignment with either of the superpowers. The Suez Crisis of 1956, over which the Commonwealth was badly split, underlined the decline of Britain's power.

Small Nations Join

But the Commonwealth did not die. During the 1950s it was assumed that some 30 smaller countries could never qualify for independence, and that for Commonwealth membership a country would need a population of at least two million. Cyprus became the critical test case. With a population of only 500,000, it became independent in 1960 and joined the Commonwealth in 1961. This was the precedent for the small states – many of them island nations in the Caribbean and elsewhere. From 1960 to 1980 the decolonization of the empire was virtually completed and small states (one million or less in population) made up the majority of Commonwealth members.

The decision to create the Secretariat in 1965 was made by 21 members. The first secretary-general was a Canadian, Arnold Smith. By 1970 there were 31 Commonwealth members, by 1980 the total was 44 and in 1990 the 50th joined. South Africa was not a member between 1961 and 1994, nor was Pakistan between 1973 and 1989. Fiji's membership lapsed between 1987 and 1997; it rejoined in 2001, was suspended in 2006, and rejoined in 2014.

Periodic prime ministers' meetings, held from 1944-1961 at 10 Downing Street in London (the British prime minister's residence), were succeeded by large Commonwealth heads of government meetings (called CHOGMs) at different venues every two years, beginning in Singapore in 1971. Canada hosted two, in Ottawa (1973) and Vancouver (1987). The meetings have returned to Britain only twice, in 1977 and 1997. A valuable tradition, started by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1973, is the Retreat, when heads of government and their spouses spend the weekend away from their officials during CHOGMs.

Racism, Democracy and Political Pressure

For 30 years the Commonwealth was dominated by racial conflicts. South Africa's policy of apartheid incurred such disapproval that pressure from member governments (in which Prime Minister John Diefenbaker played a major part) forced South Africa to leave the Commonwealth in 1961.

The unilateral declaration of independence by a white minority regime in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1965 led to great pressure on Britain to withhold granting legal independence until there was majority rule. This was achieved in 1980 when, after British-run elections, Zimbabwe joined the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth suspended Zimbabwe in 2002 after its presidential election was marked by politically motivated violence. Zimbabwe officially withdrew in 2003.

Throughout the 1980s increasing pressure – championed in part by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney – was exerted on South Africa to abolish apartheid. In this, most Commonwealth members wanted to go further than Britain. After the ending of apartheid in the early 1990s and the all-races election in 1994, South Africa returned to the Commonwealth as the 51st member.

By 1997, largely French-speaking Cameroon and Portuguese-speaking Mozambique had become members and Fiji had returned. Nigeria's membership was suspended in 1995 because of serious human rights violations. It rejoined in 1999.

Rwanda joined the Commonwealth in 2009, to strengthen its ties to the English-speaking world. Unlike every other member, only Rwanda and Mozambique have no history with the British Empire.

Gambia left the Commonwealth in 2013.

Membership Benefits

The benefits of Commonwealth membership can be summed up at three levels. Politically, the habits of consultation foster understanding between nations, regions and cultures. The minority of developed nations gains some appreciation of the problems of the developing nations. And the small states use the Commonwealth as their major forum.

At the functional level, technical assistance is made available through various flexible channels. Starting with the Colombo Plan in 1950, the Commonwealth went on to develop the Scholarships and Fellowships Plan in 1960, the Commonwealth Fund for Technical Co-operation in 1971 and the Commonwealth Youth Programme in 1973. The Commonwealth of Learning (a university for co-operation in distance education, founded in 1988) is located in Vancouver, BC. In 1995 the Commonwealth Private Investment Initiative was begun, to channel investment capital through regional funds.

Finally, there is the level of the "people's Commonwealth," involving hundreds of voluntary, independent, professional, philanthropic and sporting organizations. Members of educated elites share expertise and uphold professional standards. A few of these unofficial organizations date from before the First World War. Since 1966 more than 30 new professional associations have come into being with support from the Commonwealth Foundation, an autonomous body housed in the Secretariat.

Sport is the most popular element in the Commonwealth. At the national, regional and pan-Commonwealth levels, sport has become an agent of development and support to ordinary citizens. The Commonwealth Games, the association's best known event, are held every four years. As of 2016, Canada had hosted the games four times since 1930.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom