The Canadian Women's Press Club (CWPC) was founded in June 1904 in a Canadian Pacific Railway Pullman car, aboard which 16 women (half anglophone, half francophone) travelled to the St. Louis World's Fair. All but one were working journalists who covered the event. Founding members included Kathleen “Kit” Coleman, Robertine Barry, Anne-Marie Gleason and Kate Simpson Hayes. The CWPC offered female journalists professional support and development in its mission to “maintain and improve the status of journalism as a profession for women.” In 1971, its members voted to admit men and the organization became the Media Club of Canada. In 2004, the club dissolved.

I think we press women ought to get up a club or association of some kind and try to meet once a year. I don’t suppose we would claw each other too awfully and a little fun might be got out of our speech-making. Why should Canadian men journalists have all the trips and banquets?

(Kathleen Coleman, Mail and Empire, May 1904).

Women in the Press

At the turn of the 20th century, women were on the cusp of using the vote to exert political influence. Some women had already found a voice writing for many kinds of publications. During this period, women comprised just 18 per cent of the workforce — less than 60 women were identified as journalists in the 1901 Census of Canada (see Census). But women journalists were on the ascendancy, as advertisers had learned the value of what is now called “adjacency” — ads for goods and services placed next to columns and stories written by female writers and of interest to women readers, who made most household purchasing decisions. It was a group of these female writers who started the Canadian Women’s Press Club in 1904.

Female journalists of the day wrote for the society or the “woman’s” pages of various publications. These sections were filled with poetry, recipes, “household hints, church group reports” and the opinions of such female columnists as Margaret “Miggsy” Graham of The Halifax Herald.

Raised by a single mother in rural Nova Scotia, Graham began her career as a teacher, before moving to journalism in the late 1800s, writing for The Halifax Herald. After being appointed Ottawa correspondent, she wrote about federal legislation pertinent to women (and profiled political wives) for the Herald.

Creation

In June 1904, Graham met with George Henry Ham, publicity manager for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), at Montréal’s Windsor Station. Graham approached him “cyclonically,” Ham wrote in his memoir, asking why the CPR took men on all kinds of excursions but women had been “shabbily treated.” Graham reminded him that female journalists had a robust and loyal readership: it would look good on the CPR (and might well be good for business) if the railway transported women reporters to the World’s Fair. The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, was a big story. The event marked the centenary of the Louisiana Purchase (in which the United States bought millions of hectares of land in western North America from France) and showcased turn-of-the-century culture and technology.

Ham found Graham’s argument persuasive and told her that if she could assemble a dozen female reporters (with paid positions), he would get them to St. Louis. With help from Ham’s assistant Kate Simpson Hayes — who was also a columnist for the ManitobaFree Press — and francophone journalist Robertine Barry, who wrote as Françoise in Le Journal de Françoise, Graham was able to line up 16 interested women.

The voyage got underway on 16 June, when 11 of the women arrived at Windsor Station to depart aboard the brand new CPR Pullman (sleeper) car. Five more ladies boarded at stations en route to St. Louis. Only half the women from Québec were writers of reputation; most of the others used the trip to launch journalism careers with publications connected to political parties. Those who boarded in Toronto represented The Mail and Empire (see Globe and Mail), The Evening Telegram and Saturday Night magazine.

The group arrived in a St. Louis on the morning of 18 June. Officials gave them a warm welcome, and each member was provided a press pass. Kathleen “Kit” Coleman, Grace Denison and Barry had experience covering a world’s fair and were able to share what they knew with their colleagues. Marie Beaupré wrote, “From the first morning, we appreciated the advantage of belonging to the press: all barriers and all doors opened before us.” Their first stop was the Canadian pavilion, where they found their own well-stocked lounge and a telegraph operator to send their dispatches.

The newswomen covered what the fair had to offer their readers for the remainder of their stay. They departed St. Louis on Tuesday, 21 June and stopped in Chicago on their way home.

The CWPC was formed on the train, but participants’ accounts differ on whether it was en route to St. Louis or on the way home. Regardless, Coleman told her readers, the club’s guiding spirit was “camaraderie.”

Growth

Kit Coleman, one of the first female war correspondents (she covered the Spanish-American War), was the first president of the Canadian Women’s Press Club.

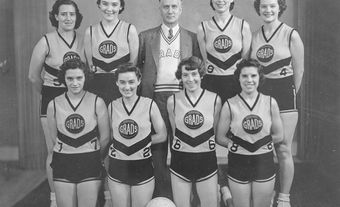

The CWPC’s first meeting in Canada was hosted in Winnipeg in June 1906; 100 women were invited and 44 came. The CWPC met every year until 1910, when, at the meeting held in Toronto, they decided to meet every three years. Membership continued to increase. In 1913, the CWPC had 219 members; in 1920, 277; in 1946, 391; and, in 1949, 437. By 1968, the CWPC had reached peak membership, with 680 members.

The CWPC initially included newspaper and magazine writers, but expanded to include editors, advertising copywriters and freelancers in print. Later, it admitted writers of “radio matter,” television and film. It also grew to include novelists (Anne of Green Gables author Lucy Maud Montgomery was a regional vice-president), writers of short fiction, playwrights, poets and historians. The fortunes of the CWPC waxed and waned over the years, as did its membership numbers, as interest in it fluctuated. Fifteen regional branches were established across Canada.

Impact

The Canadian Women’s Press Club helped women progress in the field of journalism by offering mentorship, education and professional development before there were journalism schools. It supported awards with cash prizes and created a “Beneficiary Fund” for members experiencing financial difficulties.

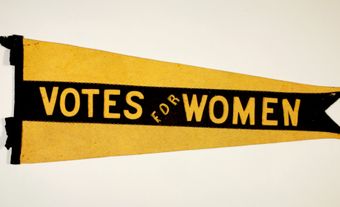

Many early CWPC members had a surprising attitude toward women’s suffrage. Some, such as Grace Denison and Katherine Hughes, were against women having the vote. Kit Coleman, a vociferous advocate for women’s rights, didn’t promote women having the vote until 1910. Later members included E. Cora Hind, Nellie McClung, Emily Murphy, Helen MacGill, Lillian Beynon Thomas and her sister Francis Marion Beynon, each campaigned successfully for women's enfranchisement. Some of these women also had careers in politics and law, and used journalism as a means of promoting social reform and to gain legal rights for women and children.

Legacy

The Canadian Women’s Press Club was the first nationally organized women's press club to remain in continuous existence. However, in June 1971, its members voted to admit men and change the organization’s name to the Media Club of Canada (now defunct).

In honour of her mother, Lois Graham Horton endowed the Margaret Graham Award in 1975. The award is presented each year to an Ottawa-area student journalist by The Media Club of Ottawa.

In 1994, 13 members took a commemorative trip to St. Louis to mark the 90th anniversary of the Canadian Women’s Press Club’s founding. A special event took place in Ottawa in 2004 called “One Hundred Years of Daring.” During this event, the CWPC donated its files to Library and Archives Canada and announced the formal end of the CWPC. The club had long provided an environment for Canadian women to flourish in journalism.

Founding Members

- Robertine Barry (wrote as Françoise in Le Journal de Françoise)

- Alice Le Boutillier Asselin (though not a journalist, Asselin was married to journalist and founder of Le Nationaliste, Olivar Asselin)

- Marie Beaupré (wrote as Hélène Dumont in La Presse)

- Kathleen Blake Coleman (wrote as Kit Coleman for the Mail and Empire)

- Mary Adelaide Dawson (wrote under her initials, M.A.D., for the Toronto Evening Telegram)

- Grace Denison (wrote as Lady Gay in Saturday Night)

- Antoinette Gérin-Lajoie (wrote under her initials, A.G.L., for L’Événement)

- Anne-Marie Gleason (wrote as Madeleine in La Patrie)

- Margaret Graham (wrote as M.G. in The Halifax Herald in 1904)

- Kate Simpson Hayes (wrote as Mary Markwell in the Manitoba Free Press)

- Katherine Hughes (wrote under her initials, K.H., for the Montreal Daily Star)

- Cécile Laberge (wrote under her own name in Le Soleil)

- Irene Currie Love (wrote as Nan in the London Advertiser)

- Amintha Plouffe (wrote as A. Plouffe in Le Journal)

- Léonise Valois (wrote as Attala in Le Canada)

- Gertrude Balmer Watt (wrote as Peggy in the Woodstock Sentinel-Review)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom