Volunteer Army

Canada was automatically at war with Germany and its allies in August 1914 as part of the British Empire. Yet the country had almost no military forces to commit to the First World War, other than a tiny navy, a small professional army of about 3,000 soldiers, and a variety of part-time militia units.

Most English-speaking Canadians had strong ties to Britain, and the desire to support the Empire was deep, especially outside Québec. Therefore, the federal government under Prime Minister Robert Borden offered, and Britain accepted, a Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) of 25,000 men. About 35,000 men soon volunteered — many of them militia members and veterans of the South African War. In October, after a brief period of training at Valcartier army camp in Québec, the First Contingent of the CEF — 30,617 strong — made the voyage for England.

"No more typical army of free men ever marched to meet an enemy," Sam Hughes, Canada's minister of militia and defence, told the departing First Contingent. "Some of you will not return — and pray God they be few. [...] For such, not only will their memory be cherished by loved ones near and dear, and by a grateful country [...] but the soldier going down in the cause of freedom never dies. Immortality is his."

Canadian Corps

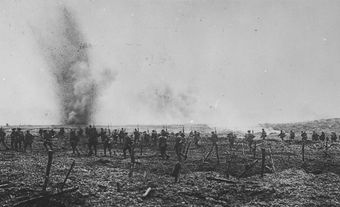

After a period of training in England, the First Contingent, formally known as the 1st Canadian Division, went to France early in 1915. The inexperienced citizen-soldiers saw their first large-scale combat at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, where they faced the first poison gas attacks launched by Germany.

The CEF was initially plagued by poor administration, largely thanks to political interference from Sam Hughes— who appointed cronies to senior officer positions, and insisted that troops fight with the unreliable, Canadian-made Ross rifle instead of the British Lee-Enfield. After Hughes was pushed out of Cabinet by Borden in 1916, however, the CEF was gradually professionalized by its British and Canadian military leadership.

At home, volunteer recruitment for the war remained strong and the CEF grew steadily until 1916, by which time a Canadian Corps had been formed with four divisions. The Corps was Canada's principle fighting force throughout the war, with a strength of 100,000 men by late 1916, including infantry, artillery and engineering troops, as well as logistical and medical units.

A National Army

The Canadian Corps took overall orders from the British military command, and was directly led until 1917 by British generals EAH Alderson and then Julian Byng. Later that year, Arthur Currie was appointed the first Canadian commander of the Corps, following the unit's capture of Vimy Ridge. As the war continued, the Corps repeatedly distinguished itself in battle at Passchendaele, Amiens, and Cambrai, gaining a reputation as one of the elite fighting forces among the Allied armies. This success, combined with the fact that it was a national corps recruited and supported by the Canadian government, allowed commanders such as Currie to exert significant independence in deciding how the Corps was used and deployed in the field.

Canadian authority over the entire CEF steadily strengthened between 1914 and 1918, assisted by the Canadian Ministry of Overseas Military Forces, set up in London in 1916. Canadian training in England became entirely a Canadian responsibility. By the end of the war, what in 1914 had been merely a colonial contingent, was now a Canadian national army.

Cavalry, Railway and Forestry

Apart from the Canadian Corps, the CEF included a variety of other units. The Canadian Cavalry Brigade also served in France; the Canadian Railway Troops served on the Western Front and provided a bridge-building unit for the Middle East; and the Canadian Forestry Corps cut timber in Britain and France for the Allied war effort. Other specialized units also operated in the Caspian Sea area, in northern Russia and eastern Siberia. The overall peak strength of the CEF was 388,038, in July 1918.

Thousands of Canadians also served during the war in the British flying services, in the Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy and in other Allied units, but these were not part of the CEF.

Conscription

Canadians volunteered in large numbers for the CEF through 1914 and 1915. By late 1916, however, recruitment had slowed to a trickle, partly due to growing awareness about the horrors of trench warfare and the slaughter on the Western Front (see Battle of the Somme). In 1917, as Canadian casualties mounted, and the need for reinforcements increased, Borden's government introduced conscription, calling up younger civilian men via the authority of the Military Service Act.

Conscription was wildly unpopular among some Canadians, especially in Québec, but it was supported elsewhere. It deeply divided the country (see Election of 1917). The Military Service Act was also inconsistently applied. Ultimately, about 100,000 men were conscripted, only 27,000 of whom were sent overseas. Of those, 24,132 served at the front. These conscripts (“MSA men”) were vital to the war effort in the final months of the conflict (see Canada’s Hundred Days). With 48 battalions of infantry in the CEF, each with roughly 1000 men, the 24,000-plus conscripts represented a boost of about 500 men per battalion in the final battles of the war.

Throughout the war, 630,000 Canadians served in the CEF, mostly volunteers. About 425,000 of those went overseas. The price of their sacrifice was high — more than 234,000 were killed or wounded, and thousands more came home alive but traumatized by their experiences.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom