Canada and the United States have a unique relationship. Two sovereign states, occupying the bulk of North America and sharing the world's longest undefended border, each reliant on the other for trade, continental security and prosperity. Despite radically different beginnings, as well as a history of war, conflict and cultural suspicion, the two countries stand as a modern example of inter-dependence and co-operation.

Revolutionary Fallout

Canada's nationhood was in many ways a by-product of the American Revolution, when the victory of the Thirteen Colonies led to the exodus of Loyalist Americans to British North America (see also Black Loyalists in British North America). Many brought with them a deep distrust of the United States and its political system. Some American revolutionaries thought the revolution incomplete while Britain retained a North American presence. Conflict seemed inevitable, and the Napoleonic Wars spilled over into North America in 1812. The War of 1812 was fought defensively by the British and half-heartedly by the Americans.

Both sides welcomed the Treaty of Ghent, which brought some settlement of outstanding problems between British North America and the United States. The Rush-Bagot Agreement of 1817 limited the presence of armed vessels on the Great Lakes. The Convention of 1818 provided for continuation of the boundary from Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains. In the east, commissioners appointed under the Treaty of Ghent sorted out boundary problems, except in northern Maine.

In the 1820s and 1830s Upper and Lower Canadians opposed to their governments looked with increasing favour upon American democracy. William Lyon Mackenzie and Louis-Joseph Papineau sought American support in their Rebellions of 1837. After his defeat Mackenzie fled to the United States, where he fomented border troubles for the following year (see Hunters' Lodges). A British show of military force and American official unwillingness to support the rebels ended the threats to British North America. In 1842 the Ashburton-Webster Treaty settled the northeastern boundary, but problems west of the Rockies were cleared up in the 1846 Oregon Treaty only after war threatened.

In 1854 fears subsided as British North America and the United States were linked by a reciprocity treaty, but they returned suddenly with the American Civil War of 1861-65. Northern Americans resented what they felt was Britain's pro-Southern sympathy. British North America and the United States managed to avoid military confrontation, but the end of the war led to new tensions because it was thought that the North might take revenge against Britain, and because Fenians were organizing to invade British North America. The Fenian Raids of 1866 failed, but spurred British North America toward Confederation the following year.

Diplomacy and Accommodation

Confederation, the subsequent withdrawal of British garrisons, and conflicts in Europe impelled Britain and Canada to seek settlement of outstanding differences with the Americans in the 1871 Treaty of Washington. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, a member of the British negotiating team, grumbled about the terms, but the treaty was useful to Canada in that the United States, through its signature, acknowledged the new nation to its north. Thereafter, Canada's concern about the American military threat diminished rapidly. There were fears of American interference as Canada established sovereignty over the North-West, but by the late 1890s both nations looked back at three decades of remarkably little conflict.

In 1898-99 a Joint High Commission, reflecting this spirit as well as the Anglo-American desire for rapprochement, sought to remedy remaining discord. The commission broke down, with only minor matters settled. One question on which agreement was not reached was the Alaska Boundary Dispute, for which another tribunal was established 1903 and which led to Canadian anger, more toward Britain than against the United States. It produced a conviction that in the future Canada must rely increasingly on its own resources and less on Britain.

Canada therefore undertook to establish direct institutional links with the United States. Best known was the International Joint Commission, established in 1909. In 1911 Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier went farther than most Canadians would go when he proposed a reciprocity agreement with the United States. In the 1911 Canadian election campaign old animosities reappeared, the Conservatives were elected and reciprocity died.

Nevertheless, the new Prime Minister Robert Borden quickly reassured the Americans that he wanted to maintain good relations. That message probably eased tensions, particularly after Canada entered the First World War (automatically under Britain) in 1914, while the United States remained neutral. When the US itself finally entered the war in 1917, the two countries recognized their common heritage and interests to an unprecedented extent.

An Emerging Friendship

Immediately after the war, Canadian politicians fancied themselves interpreters between the US and Britain. For example, at the 1921 Imperial Conference Prime Minister Arthur Meighen dissuaded Britain from renewing the Anglo-Japanese Alliance because it might bring the British Empire into conflict with the United States. Later, with Prime Minister Mackenzie King's Liberals in power, there was an ever stronger tendency to emphasize Canada's "North American" character and, by implication, its similarity to the US.

In the 1920s and 1930s Canadians and Americans mingled as never before. Canadian defence strategy was altered as planners dismissed the possibility of cross-border conflict. Economic and cultural linkages strengthened as suspicions of American influence receded. Canada and the US established legations in 1926 and no longer dealt with each other through British offices. More important was the impact of American popular culture through radio, motion pictures and the automobile. The Canadian government tried to regulate broadcasting and film but largely failed. Other organizations, such as the Roman Catholic Church in Quebec, tried moral suasion and political pressure to prevent Canadians from partaking of the most frivolous aspects of American culture.

Through the new media, Canadians became familiar with US president Franklin Roosevelt. In 1938, as another European war loomed, Roosevelt publicly promised support if Canada was ever threatened. Roosevelt did co-operate closely after the Second World War erupted in September 1939. Although the US remained neutral, Roosevelt and King reached two important agreements that formalized the American commitment: the Ogdensburg Agreement (1940) established the Permanent Joint Board on Defence, and the Hyde Park Agreement (1941) united the two economies for wartime purposes (see lend-lease). Both agreements won widespread popular approval.

Canadians' admiration for the US increased after it entered the Second World War in December 1941. Public-opinion polls indicated that many Canadians wanted to join the US. This new affection frightened King, but Canada retained and even expanded defence and other relations with the US after the war.

Co-operation and Caution

The Cold War with the Soviet Union convinced most Canadians that the US was the bulwark defending common values and security. In August 1958 Canada and the US signed a plan for joint continental air defence (NORAD), and the following year agreed to the Canada-US Defence Production Sharing Program.

Some Canadians deplored the growing links. Vincent Massey and Walter Gordon headed royal commissions on culture and economic policy that were critical of American influence in Canada. In Parliament, the 1956 Pipeline Debate and the debate on the Suez Crisis indicated that some parliamentarians also feared American influence upon Canada's government and its attitudes.

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker committed Canada to NORAD and the defence-sharing plan and quickly befriended President Dwight Eisenhower. Nevertheless, he lamented Canada's increasing distance from Britain and the extent of American cultural and other influence. This feeling turned into suspicion of the US itself when John Kennedy became president in 1961. The leaders disliked each other, and policy differences grew rapidly. Diefenbaker refused nuclear arms for Canada (see Bomarc Missile Crisis) and hesitated to back Kennedy during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The Americans openly accused Diefenbaker of failing to carry out commitments. In the 1963 general election, Diefenbaker accused the Americans of gross interference, blaming them for his election loss.

The Relationship Strains

Both countries expected better relations when the Liberals assumed power. By 1965, however, relations had deteriorated significantly as Prime Minister Lester Pearson and Canadians found it difficult to give the US the support it demanded during the Vietnam War. By 1967 the Canadian government openly expressed its disagreement with American policies in Southeast Asia. Canadians generally became less sympathetic to American influence and foreign policy. A nationalist movement demanded that American influence be significantly reduced. The first major nationalist initiatives occurred in cultural affairs, but those most offensive to Americans, such as the National Energy Program, were economic.

Relations during the first Reagan administration were strained. It was evident that the government of Pierre Trudeau and the administration of Ronald Reagan perceived international events from a different perspective. Canada, nevertheless, did permit cruise missile testing despite strong domestic opposition. In 1984 the election of Brian Mulroney's Conservatives signaled a reconciliation with the US, one which led to a weakening of nationalistic legislation and agencies such as the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA). Canadian public opinion did not reject these initiatives, and polls in 1985 and 1986 even showed strong support for Free Trade, though this support declined in 1987.

Free Trade Transformation

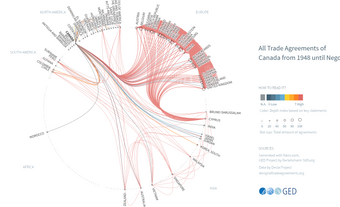

After protracted negotiations, the two governments reached a tentative trade agreement on 3 October 1987. This agreement became the central issue of the Canadian general election of 1988 which the Mulroney Conservatives decisively won. The trade agreement quickly came into effect, and Canadian-American economic relations were fundamentally changed. In 1994 the trade agreement was extended to Mexico and became known as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The trade agreement did not end disputes, in part because promised agreements on subsidies and countervailing actions did not materialize. Moreover, the disparity in size between the two partners meant that on truly controversial issues in the US Congress, such as softwood lumber, the Canadian government had to give way. Nevertheless, trade between the two countries grew dramatically with the US taking 80 per cent of Canada's exports by 1995 and Canada receiving 70 per cent of its imports from the United States. These figures lead many observers to conclude that Canada has cast its fate to North American winds. Some spoke of an inevitable political integration as a result.

Bush and Obama

Relations worsened again during the presidency of George W. Bush. After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington on 11 September 2001, Canada committed troops to the international campaign against terrorism in Afghanistan. When the Americans extended the war to Iraq in 2003, Canada, under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, refused to take part in the new campaign. The tensions came into the open public when the US ambassador publicly rebuked Canada, and when some prominent Canadians made derogatory remarks about the US president. The situation further deteriorated in 2005 when the government of Prime Minister Paul Martin announced that it would not participate in the US program to build a ballistic missile defence shield for North America.

Bush's departure from office and the inauguration of Barack Obama as president in January 2009 marked the beginning of stronger relations between the two countries. The two sides worked to improve border security by sharing more information, and by upgrading infrastructure (including a project to build a new bridge between Windsor and Detroit, the busiest of the border’s many crossing points). The goal remained to stop criminals and terrorists without hindering trade or tourism.

The government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper placed a high priority on energy exports, particularly the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, a controversial project that would transport oil from the Alberta oil sands to American markets. Environmentalists and some members of the US Congress have criticized the pipeline, which was also unpopular in some of the communities it would pass through in the western US. President Barack Obama rejected the original proposal from the TransCanada Corporation (now TC Energy), and hesitated about approving a revised version. Frustrated at this delay, Harper declared in October 2013 that Canada “won’t take ‘no’ for an answer” on Keystone XL. But ‘no’ was the answer when the Obama administration rejected the pipeline in 2015.

Justin Trudeau and Donald Trump in London, United Kingdom. December 3, 2019.

Photo: Adam Scotti (PMO)

Trump and Trudeau

The inauguration of Donald Trump as US president overturned the status quo in Canada–US relations. In 2017, in his first months in office, Trump reversed Obama’s decision on the Keystone XL project, issuing a permit that would allow the pipeline’s construction. But Trump’s arrival caused more problems than it solved. As a presidential candidate in 2016, Trump had described NAFTA as “the single worst trade deal ever approved in this country.” Upon becoming president, he threatened to cancel it. Canada, the United States, and Mexico replaced NAFTA with a new agreement in 2018, a major victory for the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The Canadian government had concentrated enormous resources on winning that battle, and win it they did, with considerable help from US politicians and from business, state, and local entities that Ottawa lobbied vigorously. The new pact was largely the same as its predecessor, but with minor changes to the sections dealing with automobiles, dairy products, wine, patents and trademarks, pharmaceuticals, and dispute resolution. Trump was delighted that his country’s name came first in the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), though the deal goes by a different name in each of the member countries. In Canada, it is known as the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA).

Trump’s presidency forced the Canadian government, particularly Prime Minister Trudeau, to practice some delicate diplomacy. On the one hand, the prime minister had to avoid offending the notoriously thin-skinned president. On the other hand, Trudeau’s values were frequently at odds with Trump’s, and Trudeau had to deal with Trump’s critics in Canada, who urged the prime minister to speak out against the president. Striking a balance was particularly difficult when Trump seemed to favour Russia and North Korea over Canada and other traditional American allies, when he banned entry to the US from citizens of Muslim countries at a time when Canada was welcoming tens of thousands of Syrian refugees, and when he defended white supremacists. In the spring of 2020, Trudeau carefully avoided commenting on Trump’s call for military action to quash the Black Lives Matter protests taking place across the US.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom