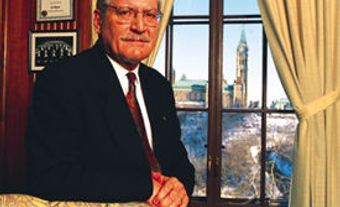

Bora Raphael Laskin, CC, FRSC, PC, legal scholar and educator, justice of the Supreme Court of Canada (1970–84), Chief Justice of Canada (1973–84) (born 5 October 1912 in Fort William [now Thunder Bay], ON; died 26 March 1984 in Ottawa, ON). Bora Laskin is generally considered Canada’s first great legal scholar, and one of the greatest legal minds in Canadian history. A towering intellectual, Laskin overcame pervasive anti-Semitism in the legal profession to become the 14th chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. He also played an integral role in modernizing the University of Toronto’s law school. His decisions and dissents helped shape a new era of Canadian civil liberties, much of which culminated in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. Laskin was an ardent Canadian federalist. He sided with Pierre Trudeau on constitutional issues and argued in favour of strong federalism via a powerful and public Supreme Court.

Early Life and Family

Bora Laskin was born in Fort William (now Thunder Bay) in 1912. His parents never used his Hebrew name, Raphael. The origin of his English name is unclear, though it may have been an homage to US senator William E. Borah, known for his pro-Jewish views. Laskin’s parents, Mendel (Max) Laskin and Bluma Zingel (or Singel), were Russian immigrants. Max Laskin owned a furniture store in Port Arthur.

Bora had two brothers: Saul and Charles. Saul was the last mayor of Port Arthur and the first mayor of Thunder Bay (formed by a merger of Port Arthur and Fort William). Charles worked in the clothing industry. Young Bora Laskin attended public school and then Hebrew school in the afternoon. As such, he became trilingual in English, Hebrew and Yiddish. He became president of Fort William’s Young Judaea club and taught for two years at the Fort William Talmud Torah. Described as a brilliant public speaker in his youth, Laskin won the Toronto Star cup in his final year of high school. Prior to starting university, he attended Fort William Collegiate Institute.

Education and Early Career

Bora Laskin arrived in Toronto in 1930 to start his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. This was a major sacrifice for his family, given the economic conditions brought on by the beginning of the Great Depression the year before. Laskin’s brother Saul, for example, was not able to attend university because of the family’s financial hardship. Fortunately, Laskin’s grades were high enough that he was able to enter directly into the second year of W.P.M. Kennedy's honours law course. Laskin immersed himself in campus life, becoming involved in student politics, debating and sports, particularly track and field and rowing. He also joined a Jewish fraternity, Sigma Alpha Mu.

After graduating in 1933, Laskin enrolled in Osgoode Hall Law School. The Osgoode Hall program combined lectures and articling. Before he was allowed to enroll, however, Laskin had to find someone who would give him employment and sign his articles. Laskin found it difficult to find a law firm that would take him on, due to widespread anti-Semitism in the legal profession. In his first year at Osgoode, Laskin worked for his fraternity brother Samuel Gotfrid.

Laskin graduated near the top of his class at Osgoode. He articled from 1933 to 1936. He earned an MA from the University of Toronto in 1935 and received his LLB in 1936. He then attended Harvard Law School on a scholarship. While there, he studied under some of the greatest legal minds of the era, including Felix Frankfurter, Roscoe Pound and Zechariah Chafee. Frankfurter would later become a US Supreme Court Justice.

Out of 17 students in his program at Harvard, Laskin was one of only two to graduate cum laude. He earned an LLM from Harvard Law School in 1937. He was called to the bar the same year but was unable to start a career with a Toronto law firm. Instead of practising law, Laskin began his career writing headnotes for the Canadian Abridgment. To make ends meet, he co-edited Revised Statutes of Ontario.

Personal Life and Teaching Career

In 1938, Bora Laskin married Peggy Tenenbaum. They had two children together. Their son, John I. Laskin, was a long-serving justice on the Ontario Court of Appeal. Laskin’s nephew, John B. Laskin, became a justice on the Federal Court of Appeal and taught law at the University of Toronto.

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Laskin did not enlist. The reasons why were never made clear, but the issue came up years later when he was nominated to the Supreme Court. Laskin’s decision to not volunteer may have had to do with the fact that he was recently married, as well as the fact that his parents had sacrificed greatly for him to attend university.

In 1940, still unable to find work as a lawyer in Toronto, Laskin took a job offered to him by W.P.M. Kennedy to teach law at the University of Toronto. Laskin taught for the next quarter century, nearly all at the University of Toronto (except for 1945–49, when he taught at Osgoode Hall). In 1945, Laskin decided to join Osgoode Hall with a long-term plan to then move to the University of Toronto law school once it was revamped. His goal was to create the premiere law school in Canada, affiliated with a university and not the law society.

During this time, Laskin authored many legal texts, including Canadian Constitutional Law (1951). It became the standard textbook for Canadian law schools for a generation. He also served as the associate editor of Dominion Law Reports and Canadian Criminal Cases for 23 years. He was affectionately known as “Moses the Law Giver” by his students. He earned a reputation as a brilliant scholar and an inspiring teacher.

In 1964, Laskin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He helped create the Canadian Association of University Teachers and was its president in 1964–65. Around this time, Laskin joined — and eventually chaired — the Legal Affairs Committee of the Canadian Jewish Congress. In this capacity, he prepared briefs and draft legislation that were instrumental in fashioning Canada’s human rights laws.

Early Judicial Career

Bora Laskin was appointed to the Ontario Court of Appeal in 1965, making him the court’s first Jewish justice. The following year, Laskin chaired the board of directors of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. In 1967, he joined the board of York University.

Laskin was a major champion of civil liberties while on the Ontario Court of Appeal. He frequently dissented from the majority on the court. His courage and integrity gained the attention of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. In 1970, Trudeau made Laskin his first appointment to the Supreme Court. Laskin was the first Jewish person to be appointed to the Court. He was also the first Canadian to not belong to either the French or English ethnolinguistic groups to be so appointed, as well as the Court’s youngest ever justice. During his time on the Court, Laskin became known as the “Great Dissenter” because he frequently dissented with the mostly conservative opinions of the court.

In 1971, Laskin became the chancellor of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay. He held that position until 1980.

Chief Justice of Canada (1973–1984)

Having already earned a reputation as a progressive reformer, Bora Laskin was named chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada on 27 December 1973. He became the first Jewish Canadian to hold that position, as well as the youngest. The decision generated great controversy because convention holds that the most senior justice be appointed to the role of chief justice.

Notable Legal Cases

- Drummond Wren (1945). Laskin worked behind the scenes assisting the complainant on behalf of the Canadian Jewish Congress. The High Court of Justice of Ontario decided that covenants restricting the sale of land to specific people (in this case, Jews) were invalid. This case was later cited in similar cases regarding racially or culturally biased prohibitive covenants.

- Noble and Wolf v. Alley (1950). Similar to the Drummond Wren case, Laskin counselled the complainants in their successful appeal to the Supreme Court.

- Murdoch v. Murdoch (1973). Laskin was the sole dissenting judge. The majority of the court decided that Irene Murdoch was not owed any part of the ranch she ran with her husband. The majority decision indicated Murdoch’s labour “was the work done by any ranch wife.” In his dissenting opinion, Laskin argued that a constructive trust based on equity could be found (i.e., that both Murdochs contributed to the ranch equally or equitably). The Murdoch case was championed by Canadian feminists and eventually led to reforms in matrimonial property law.

- Attorney General of Canada v. Lavell (1974). Laskin dissented against majority court opinion, which upheld that Indigenous women lost their status if they married non-Indigenous men. Laskin argued that this compounded racial discrimination with gender discrimination.

- Morgentaler v. The Queen (1975). This was the first of three SCC cases brought by Dr. Henry Morgentaler to challenge the prohibition of abortion. Laskin dissented against the SCC determination that abortion law was properly passed by Parliament. Morgentaler succeeded in decriminalizing abortion in 1988, thanks to the Charter.

- Patriation Reference (1981). Perhaps the most important constitutional law ruling in Canadian history. The SCC found that there is no legal barrier to the federal government seeking a constitutional amendment without provincial consent. Laskin supported this determination. However, the SCC also decided that there is an unwritten constitutional convention wherein the approval of a majority of the provinces is required for constitutional amendments.

Honours

Bora Laskin was made a Companion of the Order of Canada “for his service to our country, most notably as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada” on 13 March 1984. He died less than two weeks later. Pierre Trudeau called Laskin “a great Canadian, a brilliant legal mind who presided over the Supreme Court during such an important period in the search for the Canadian identity.” (See also Canadian Identity.)

Over the course of his career, Laskin wrote six books, seven commission reports, and dozens of legal articles. He received 27 honorary degrees from universities in Canada, Britain, the United States, Israel and Italy. Lakehead University, in Laskin’s hometown of Thunder Bay, named a building after him, as well as their law school. The University of Toronto’s main law library is named for Laskin — a tribute to the role he played in remaking the university’s law faculty/law school as the premiere professional and academic law program in Ontario. The Bora Laskin Law Society in Ottawa was named in his honour, as was The Laskin (an annual bilingual moot court competition in which most of Canada’s law schools participate).

Legacy

Along with Pierre Trudeau, Bora Laskin was “midwife to the ‘Just Society.’” In the words of Superior Court of Ontario justice Lorne Sossin, Laskin was “the standard-bearer for an intellectually rigorous, modern, progressive legal age for Canada.” During his career on the Ontario Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), Laskin was described as having “embarked on a quest to make the judiciary more responsive to modern Canadian expectations of justice and fundamental rights.” According to former SCC justice Ian Binnie, Laskin was instrumental in the creation of a law school separate from the legal profession, and may have taught the first civil liberties course at a Canadian law school. The first academic on the Supreme Court, Laskin was known as a champion of civil liberties and an innovative educator who helped bring legal education into the modern era.

(See also Judiciary in Canada; Court System of Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom