The Barr Colonists were a group of nearly 2,000 British settler colonists who immigrated to Canada in 1903 and founded the “Barr Colony.” The all-British colony was named after their leader, Isaac Barr. Despite disorganized leadership, poor preparation and hardship, the colony survived with the help of the federal government and their Indigenous neighbours. The Barr Colony grew into what is now Lloydminster, a city that straddles the Alberta-Saskatchewan border.

Origins

By 1900, a large majority of the settler population in Canada had been born in the country; most were of British descent. The widespread sentiment was that more immigrants were necessary and that such immigrants should come predominantly from Britain. This sentiment was often rooted in ideas about racial superiority, although some Canadians nevertheless viewed upper-class Britons as lazy workers, leading to “No English Need Apply” signs in some shopwindows. (See Immigration to Canada; Immigration Policy in Canada; English Canadians.)

The Barr Colony was the brainchild of Isaac Montgomery Barr (1847–1937). Born in Ontario to parents of Irish descent, Barr was an Anglican minister who lived in Ireland and the United States before moving to England in January 1902. Inspired by Cecil Rhodes’ African colonization schemes, Barr began promoting the creation of an all-British settlement in Canada. He envisioned the colony beginning with 25 families from agricultural backgrounds and enlarged by subsequent group immigration. His promotional efforts attracted hundreds of enquiries, in large part from unemployed veterans of the South African War (Boer War).

Around this same time, another Anglican minister, George Exton Lloyd (1861–1940), published a letter in an English newspaper urging British immigration to Canada. The letter was widely reprinted in other papers and garnered thousands of replies. Born in England, Lloyd had lived in Canada for over a decade, in both Ontario and New Brunswick, with brief stints in Jamaica and the United States. He returned to England in 1900 to work for the Colonial and Continental Church Society, where he was responsible for promoting emigration to Canada. Lloyd’s letter attracted Barr’s attention and after meeting, the two agreed to work together. Barr published a pamphlet to promote the scheme and then sailed to Canada to select an exact site and arrange for colonists’ transportation to it, while Lloyd stayed behind at their office, responding to enquiries and interviewing would-be colonists.

Planning

Barr reserved 16 townships from the federal government in a remote area approximately 240 km from Saskatoon but made few other concrete plans. This led worried immigration officials to make their own backup plans, such as establishing rest sites along the path between the end of the railway to the proposed settlement and hiring guides to help with the trip. They also hired farm instructors, to teach inexperienced colonists, and a surveyor and a land agent, to assist with the division of the land.

These efforts were more rooted in self-preservation than any enthusiasm about the project: civil servants worried that if the scheme went poorly, it would discourage future immigration from Britain, especially since Barr had falsely claimed that his plan had been endorsed by the Department of the Interior (then in charge of matters relating to immigration).

The officials were right to worry, for Barr had insufficient funds to bankroll the project. This led to increasingly farfetched plans to extract more money from the colonists to ensure the venture’s success, such as a series of cooperatives for hospitals, transportation and supplies, but most of these never came to fruition. Financial pressures also led Barr to accept an increasing number of colonists, some 1,962 in all. Few were experienced farmers, and in contrast to Barr’s original plan and his repeated promises, only 22 percent of colonists listed occupations that were even vaguely related to agriculture.

The Trip

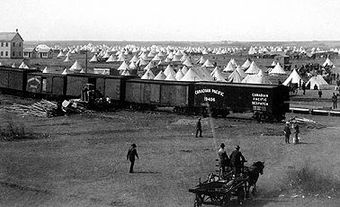

The colonists sailed from Liverpool on 31 March 1903 aboard the SS Lake Manitoba, a ship woefully underequipped to handle such a large group. Complaints included overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, seasickness, poor food and stale drinking water. The ship docked in Saint John, New Brunswick, on 11 April 1903, and colonists boarded four trains that steamed them towards the prairies. Four hundred people disembarked at Winnipeg hoping to work for other farmers and gain the necessary experience and capital to later set out on their own. The remainder arrived in Saskatoon on April 17. There, most colonists lived in “Canvas Town,” a tent city that had been erected owing to insufficient accommodations in the small village.

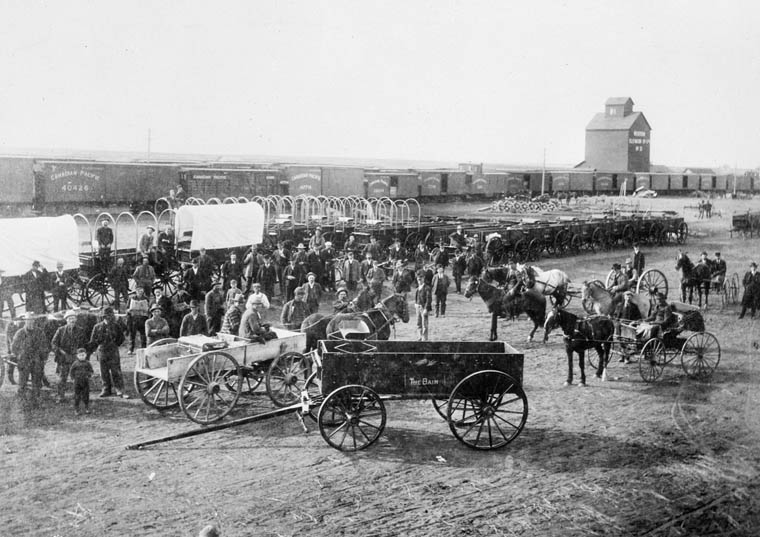

Their numbers decreased again when a handful of families opted to return to England, and when officials found that an additional 200 people had insufficient funds to continue and found jobs for them, mainly on railway construction in Prince Albert and Moose Jaw. The remaining settlers started on the trail for Battleford, a five-day overland trip. Some turned back along the way, while others stayed in Battleford to earn more money. Eventually, the remaining 1,200–1,600 set out on the final leg of the trip to the reserved lots.

The Founding

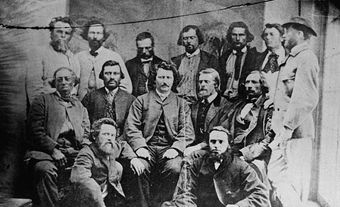

Upon their arrival, the colonists, resentful of Barr’s poor planning, quickly ousted him, and he left the community shortly afterwards. The colonists then turned leadership over to Lloyd and a committee of 12, named the colony “Britannia” and named its first town “Lloydminster.” Not everyone was happy with Lloyd, however, as he was rigidly insistent on keeping the community all-British and free of alcohol; the former led some settlers to leave, while the latter divided the community internally.

Despite the conflicts, the colonists worked hard and by October 1903, the town consisted of over 75 houses, more than 10 shops, three restaurants, a post office and telegraph office. However, it did not remain a British settlement, as the government opened the reserved land to Canadian and American settlers.

The early years were hard for most, particularly those who had little farming experience or capital (although occasionally an amateur like J.C. Hill became quite successful). Alice and William Rendell were experienced farmers and well-provisioned, so they spent their earliest years constructing a timber house, working the land and writing home. Many others, like Nathaniel Jones and his family, slept in sod houses, the cold dictating that the bed, woodpile and stove be so closely arranged that the owner could feed the fire without getting out of bed.

The colonists benefited greatly from the ties they forged with the residents of the nearby Onion Lake Cree Nation. Cree freighters had been hired to help colonists make the journey from Battleford to the settlement. Once the colonists arrived, Cree people worked as guides for English hunters, taught them how to trap and sold them moccasins, logs, lumber and meat. Others were hired by the colonists to make thatch roofs for their sod houses. The federal government’s treatment of the two groups, however, could not have been more different: they worked to suppress Cree culture through residential schooling, while aiding the all-British settler colony, a venture organized around ethnicity.

The Aftermath

The year 1905 marked a turning point for the colony for three reasons: Lloyd accepted the position of Archdeacon and General Superintendent of all “white missions” for the Anglican diocese and moved to Prince Albert (where he later became an outspoken nativist); the tracks of the Canadian Northern Railway reached the settlement, ending its isolation; and the provincial boundary between Saskatchewan and Alberta was drawn, dividing Lloydminster into two separate towns in two different provinces.

The two towns were eventually amalgamated in 1930, and the singular town was later incorporated as a city in 1958. Although the joint population in 1906 was only 519, this number has grown steadily. In 2021, the population numbered over 31,000.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom