Ballet

It is mostly, although not necessarily, performed to music, and when combined with sets and costumes is capable of creating lavish stage spectacles.

Today, the word ballet is used more loosely to describe not only the classic academic dance with its well-defined technique but also more contemporary, free-ranging forms of theatrical dancing. Ballet, in its traditional form, evolved from the early court entertainments of Renaissance Italy. These dances were introduced to France by Italian masters in the 16th century. The ballet de cour (court ballet) developed from social dancing for the aristocracy to become elaborate, spectacular, and highly theatrical presentations used symbolically to demonstrate the wealth and power of French monarchs. The most famous was Le Ballet comique de la Reine Louise, mounted in Paris (1581) as part of 2 weeks of celebration marking an important royal marriage. The 5-hour performance was remarkable in offering a continuous dramatic narrative.

Although these court dances continued, the development of ballet as a theatrical art gained momentum with the emergence of the popular opera-ballet in late 17th-century France. Dance interludes were placed between the vocal scenes. Ballet increasingly became a professional activity for trained dancers. The opera-ballet allowed little room for the independent development of ballet. In the 18th century, however, dance masters began to create entertainments in which a story was told solely through movement, both mime and dance.

The work of French choreographer and theorist Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810) was particularly influential in advancing the cause of the ballet d'action. His Letters on Dancing and Ballets (1760) rejected the subservient role of dancing within the tradition of the opera-ballet and strongly advocated the more dramatic style. This required a more expressive style of dancing than the rather formal dance movements of the opera-ballet. The ballet d'action had as its aim the establishment of dance as a discrete theatrical art. Passages of dancing have continued to be included in operas into the present era both as a diversion and as a narrative component, but from the late 18th century ballet progressively asserted its right to a place of its own among the theatrical arts. La Fille mal gardée (1789) is among the earliest ballets from this period to have survived, albeit in reworked form, into our age.

The first half of the 19th century witnessed important developments in ballet. The Italian dancer, choreographer and teacher Carlo Blasis (1797-1878) wrote extensively about his theories of ballet and published an important codification of its technique.

At the same time, European middle-class audiences flocked to see such famous ballerinas as Marie Taglioni, Fanny Elssler and Carlotta Grisi. The technical developments that allowed ballerinas to simulate ethereal lightness by dancing on the tips of their toes in specially constructed shoes gave ballet one of its most enduring motifs. Indeed, as the century progressed, the art of ballet in France and much of Europe came to be dominated by the ballerina, with male dancers taking a secondary role. Men were so marginalized that it was not uncommon for lead male roles to be performed en travestie by women. Although the intellectual and aesthetic concerns of the Romantic Movement were slow to touch ballet, works such as Les Sylphides (1832) and Giselle (1841), with their mix of natural and super natural elements, captured the public imagination and remain audience favourites even today.

Ballet in France degenerated artistically during the latter part of the 19th century but thrived in Denmark, under the brilliant ballet master August Bournonville (1805-79), and in Russia, where the French-born Marius Petipa created, among many others, such enduringly popular ballets as The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake.

Even as Diaghilev was helping to restore and rejuvenate ballet in the West, other very different forms of theatrical dance were being developed in Europe and North America. In large part these forms rejected ballet on the grounds that it was antique and

irrelevant. What came to be known generically as modern dance grew from a different set of ideas about human movement and produced its own distinct type of dance theatre. These

two streams of Western theatrical dance, classical and modern, continued to develop independently and often in vocal opposition. Ballet aficionados would commonly deride modern dance as "barefoot ballet" and modern dance advocates would depict the ballerina's

blocked pointe shoe as unnatural and as an instrument of torture. From the 1960s on, however, the division between ballet and modern dance has steadily melted away. A process of cross-fertilization has seen a partial blending of techniques and styles.

Until the middle of the 20th century Canadians were more often spectators than participants in the art of ballet. The French colonization of the St Lawrence Valley from the 17th century onwards had seen the introduction of dance masters to Canada, but their activities were directed mostly to teaching children of the rich. The real beginnings of professional ballet in Canada date from the 1930s, when such important teachers as Boris Volkoff in Toronto, Gwendolen Osborne in Ottawa, Gérald Crevier in Montréal and June Roper in Vancouver began to produce dancers equipped to pursue professional careers.

Without Canadian companies for them to dance in, however, these talented artists had to find work abroad. Patricia Wilde from Ottawa and Melissa Hayden from Toronto are 2 outstanding examples. During the early 1950s both rose to international stardom dancing in American ballet companies. More than a decade later, Lynn Seymour, who was born in Alberta and initially trained in Vancouver, felt it necessary to pursue her career overseas, in England. As a dancer in the Royal Ballet she came to be hailed as one of the century's greatest dramatic ballerinas.

In 1938, however, 2 English ballet teachers, Gweneth Lloyd and Betty Farrally, established a ballet club that by 1949 had evolved into Canada's first truly professional company, the Winnipeg (from 1953, Royal Winnipeg) Ballet. In Toronto, a distinguished British dancer and choreographer, Celia Franca, was invited by local ballet supporters to establish the National Ballet of Canada (1951); and 7 years later Les Grands Ballets Canadiens was founded in Montréal by another immigrant, Ludmilla Chiriaeff. Also in 1958, Canadian Ruth Carse founded a small amateur company in Edmonton, which within a decade had grown to become the fully professional Alberta Ballet. By the early 1990s the company, relocated in Calgary, was touring nationally and overseas. After various aborted attempts to establish a permanent ballet troupe in Vancouver, Ballet British Columbia was firmly established in 1986. At the same time, Ballet Jörgen, a small, highly mobile troupe with a mandate to develop new choreographers, was gaining strength in Toronto. Each of these ballet companies has developed its own particular identity and together they now provide work for about 160 dancers.

Canadian ballet choreographers have also emerged in parallel with the growth of companies across the country. In the early 1960s, Brian Macdonald and Fernand Nault were among the first Canadian choreographers to establish international reputations, to be followed by Norbert Vesak and later by James Kudelka, John Alleyne, Mark Godden and Jean Grand-Maître.

Despite its relatively short history and chronic funding problems, ballet in Canada has established remarkably deep roots. Schools such as those associated with the National Ballet and Royal Winnipeg Ballet have proved able to train dancers of international calibre. Canadian dancers trained in these schools, such as Veronica Tennant, Karen Kain, Frank Augustyn, Evelyn Hart and Rex Harrington, have won international acclaim without the need to join foreign companies. Canadian dancers who have felt the urge to work abroad have earned respect for their sound training and performance abilities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

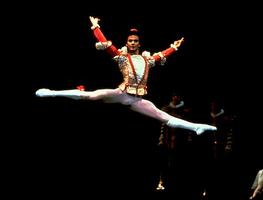

The Sleeping Beauty , 1975 (photo by Anthony Crickmay, courtesy National Ballet

of Canada Archives).", "caption_fr": "Karen Kain et Frank Augustyn interprètent le pas de deux de l'Oiseau bleu, tiré du ballet La Belle au bois dormant, 1975 (photographie d'Anthony Crickmay; avec la permission des archives du Ballet national du Canada).",

"title_en": "Bluebird Pas de Deux", "title_fr": "Pas de deux de l'Oiseau bleu"}' title='Bluebird Pas de Deux' alt='Bluebird Pas de Deux' />

The Sleeping Beauty , 1975 (photo by Anthony Crickmay, courtesy National Ballet

of Canada Archives).", "caption_fr": "Karen Kain et Frank Augustyn interprètent le pas de deux de l'Oiseau bleu, tiré du ballet La Belle au bois dormant, 1975 (photographie d'Anthony Crickmay; avec la permission des archives du Ballet national du Canada).",

"title_en": "Bluebird Pas de Deux", "title_fr": "Pas de deux de l'Oiseau bleu"}' title='Bluebird Pas de Deux' alt='Bluebird Pas de Deux' />