Arctic sovereignty is a key part of Canada’s history and future. The country has 162,000 km of Arctic coastline. Forty per cent of Canada’s landmass is in its three northern territories. Sovereignty over the area has become a national priority for Canadian governments in the 21st century. There has been growing international interest in the Arctic due to resource development, climate change, control of the Northwest Passage and access to transportation routes. As Prime Minister Stephen Harper said in 2008, “The geopolitical importance of the Arctic and Canada’s interests in it have never been greater.”

International Law

A country’s claim to sovereignty over land or sea depends on the complexities of international law. Generally accepted proofs of sovereignty include discovery of territory; the ceding of territory from one nation to another; conquest; and administration. The historical notion that Indigenous people have no legal title to the land they live in — that they do not “own” it — has been central to the idea of European sovereignty over North American territory. This way of thinking has asserted that Indigenous people merely have Indigenous rights, particularly “usufructuary” rights, or the right to use the land and its products. (See also Aboriginal Title.)

In recent years, however, the federal government, particularly under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, has argued that the long-time presence of Inuit and other Indigenous peoples in Canada’s Arctic territories has helped establish Canada’s historic title to those lands.

(courtesy Native Land Digital / Native-Land.ca)

Canada’s Claim to the North

Canada’s claim to its North rests first on the charter granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) by Charles II in 1670. This gave the company legal title to Rupert’s Land (the watershed of Hudson Bay, or about half of present-day Canada). In 1821, the rest of the present-day Northwest Territories and Nunavut south of the Arctic Coast were added to the HBC charter. The company transferred title to its lands to Canada in June 1870; the new Dominion thus acquired sovereignty over all of the present-day Northwest Territories and Nunavut except for the Arctic islands. This sovereignty has never been questioned.

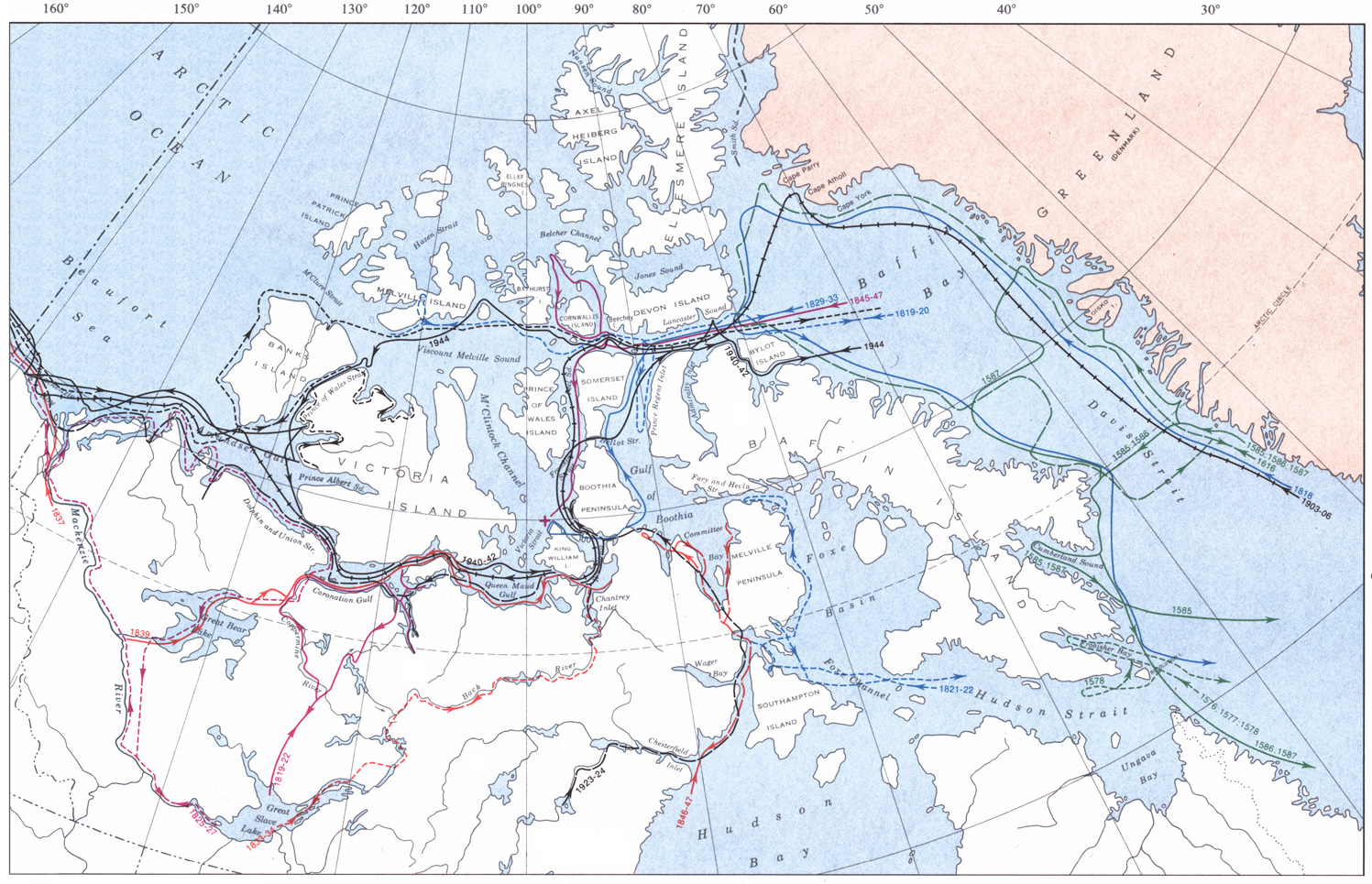

Where doubt has risen over Canada’s claims to Arctic sovereignty is in the islands north of the Canadian mainland. Some of the early explorers here were British (Martin Frobisher in 1576; John Davis in 1585 and 1587, and others). But many of these islands were reached and explored by Scandinavians or Americans. (See Arctic Exploration.)

In July 1880, the British government transferred the rest of its possessions in the Arctic to Canada. This included “all Islands adjacent to any such Territories” whether reached or not. This is a feeble basis for a claim of sovereignty, because the British had a dubious right to give Canada islands which had not yet been discovered by foreigners. The Colonial Boundaries Act of 1895 attempted to alleviate these doubts; but it still contained a vague definition of the territory claimed.

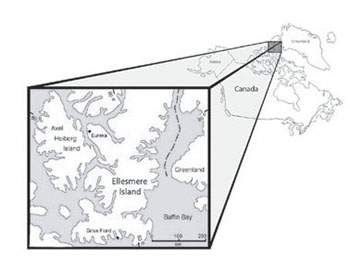

Meanwhile, although the United States made no formal claims, they were particularly active around Ellesmere Island. Lieutenant A. Greely led a scientific expedition there from 1881 to 1884. In 1909, Robert Peary reached the North Pole from his base on northern Ellesmere. The greatest danger to Canada’s claims came via the expedition of Otto Sverdrup; between 1898 and 1902, he reached Axel Heiberg Island, Ellef Ringnes Island and Amund Ringnes Island. Sverdrup is believed to be the first European to set foot on them. He claimed all his discoveries — about 275,000 km2 — for Norway. Other large Arctic islands were also reached by non-British explorers.

Early Voyages and J.E. Bernier

In the 1880s, the Canadian government sponsored periodic voyages to the Eastern Arctic. The goal was to establish a presence there in support of its territorial claims. In 1897, a series of Arctic patrols began. Captain William Wakeham raised the Royal Union Flag on Kekerten Island, claiming “Baffin’s Land” for the Dominion. (See Baffin Island.) In 1904, A.P. Low sailed up to Cape Herschel on Ellesmere Island, which he mapped and claimed for Canada. Captain J.E. Bernier carried out numerous voyages between 1904 and 1925. Perhaps the most important was that of 1909; he set up a plaque on Melville Island, claiming the Arctic archipelago for Canada, from the mainland to the North Pole.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE, 1913–18), which included many Iñupiat (Alaskan Inuit), Inuvialuit (Western Arctic Inuit) and Inuinnait (Copper Inuit), asserted Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic archipelago; it also remade the map of the Far North and collected a vast amount of scientific data. It was the first expedition financed and supported by the Canadian government to explore the Western Arctic. The CAE was commanded by the controversial explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson; he charted the last of the Arctic islands and claimed them for Canada.

However, these and similarly symbolic acts of raising flags and erecting plaques carried little weight in international law since they were not accompanied by effective occupation or administration.

Police Posts Established

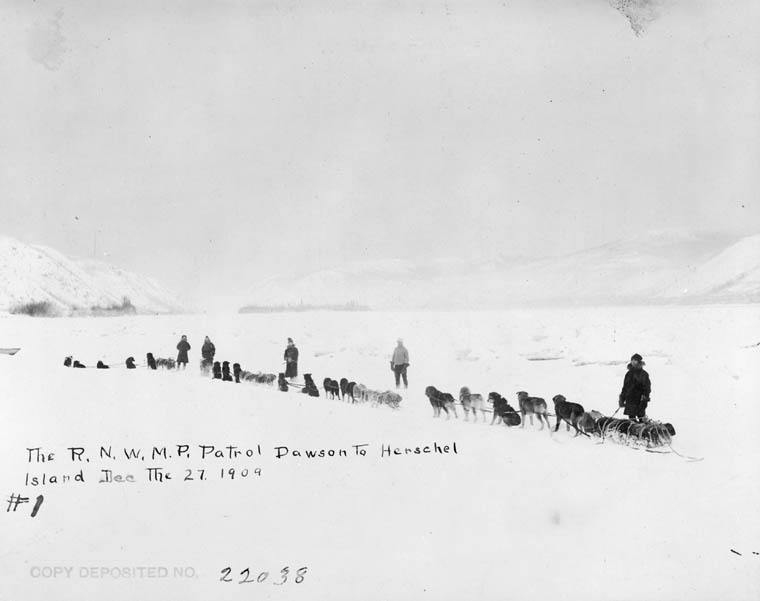

The first vigorous assertion of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic came with the establishment of a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) post at Herschel Island in 1903. It was set up to control the activities of American whalers in the Western Arctic. It enforced Canadian laws and flew the flag in the region, making Canada’s sovereignty there unquestionable.

After the First World War, the Americans and Danes showed signs of ignoring Canada’s claims to the High Arctic; particularly to Ellesmere Island, which the Danish government stated in 1919 was a no-man’s land. This was a direct challenge to Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. It was met by a plan for effective occupation of Ellesmere and other islands. In 1922, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) posts were established at Craig Harbour and at the south end of the island; as well as at Pond Inlet on Baffin Island. In 1923, another detachment was placed at Pangnirtung, and in 1924 at Dundas Harbour, on Devon Island. In 1926, the Bache Peninsula detachment was established on the east coast of Ellesmere Island, at 79° N latitude. (See also Bache Peninsula Archaeological Sites.)

There were no Canadians living within hundreds of kilometres of Bache Peninsula. But the RCMP operated a post office there (with mail delivery once a year) because operation of a post office was an internationally recognized proof of sovereignty. The RCMP also continued its extensive patrols. On Ellesmere Island, where there was no population, these were exploratory. In 1929, a patrol commanded by Inspector A.H. Joy covered 3,000 km by dog team. Some new land was reached. In 1928, Constable T.C. Makinson reached the large inlet off Smith Sound that now bears his name.

On Baffin Island, the police visited each Inuit camp annually, took the census, explained the law and reported to Ottawa on local conditions. These were all demonstrations of sovereignty. Where necessary, they enforced the criminal law, as in the murder of the Newfoundland trader Robert Janes near Pond Inlet in 1920. This activity further strengthened Canada’s claims to the Arctic. (See also Alikomiak and Tatimagana.) In 1931, Norway formally abandoned its claim to the Sverdrup Islands. Ottawa also paid Sverdrup $67,000 for the records of his expeditions. This made Canada’s formal claim secure.

Canadian Rangers

Approximately 5,000 Rangers, from 200 communities, help promote Canadian sovereignty in isolated regions today. Their duties include reporting unusual activities; surveillance and sovereignty patrols; search and rescue; disaster relief; and support of Armed Forces operations and survival training.

High Arctic Relocation

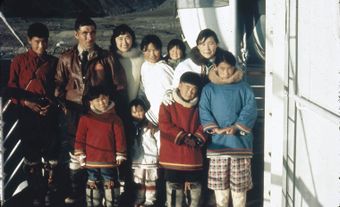

Also amid Cold War tensions in the postwar era, the Canadian government decided to populate Ellesmere and Cornwallis islands with Inuit, even though both areas were uninhabited. In 1953 and 1955, the RCMP moved a total of 92 Inuit from Inukjuak (formerly Port Harrison) in northern Quebec, and Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) in what is now Nunavut, to settle two locations on the High Arctic islands: Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord. The government ordered the relocations to establish sovereignty in the Arctic. It promised improved housing, education and living conditions. The Inuit were assured plentiful wildlife, but soon found that they had been misled, and endured hardships. Though Inuit were promised an option to return home after two years, they were not permitted to do so. (See Inuit High Arctic Relocations in Canada.)

Challenges Enforcing Arctic Sovereignty

Canada’s claim to its Arctic land area is now secure. But the fact that large sections are uninhabited and virtually undefended raises the possibility that it may not be secure forever. More important is the fact that there is international consensus only about the land area; the channels and straits — particularly the Northwest Passage — are not universally recognized as Canadian.

Canada regards the channels and straits as internal waters through which foreign vessels must request permission to pass. With the prospect of bringing home oil from Arctic discoveries off Alaska, the United States has increasingly seen the Northwest Passage as international waters, open to all. It demonstrated this belief by sending the oil tanker Manhattan (1969) and the United States Coast Guard Ship Polar Sea (1985) into Canada’s Arctic. The Manhattan was escorted through the Northwest Passage with the help of Canadian and American icebreakers. The US did not officially seek permission for the Polar Sea voyage from the Canadian government; but Canada was notified about the event. Both countries co-operated on the matter, and Canada stationed official observers onboard during the voyage.

As a result of the 1985 voyage of the Polar Sea, External Affairs Minister Joe Clark put forward plans for a new $500 million icebreaker. It fell victim to cost-cutting and was never built. In 1987, the federal government also announced that it would build and station nuclear-powered submarines in Arctic waters; but this had as much to do with Canada’s role in continental defence as with sovereignty. After much fanfare and political wrangling, the plan to build or buy submarines was quietly abandoned. In early 1996, another plan to patrol the Arctic waters by submarine was abandoned as too expensive.

In 2010, the federal government announced plans to build a fleet of six to eight “ice-capable, Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships,” to enforce Canada’s sovereignty on its coasts, including the Arctic. Due to delays, the ships are not yet operational.

Hans Island (Tartupaluk) Dispute

Canada and Denmark long argued over a tiny, uninhabited island; a 1.2 km2 barren rock halfway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland known as Hans Island. (The Inuit name for the island, a traditional Inuit hunting ground, is Tartupaluk.)

In 1973, the two countries agreed on a maritime boundary dividing the Nares Strait between Ellesmere Island and Greenland; but they could not agree on the ownership of Hans Island, which is an even 18 km from each country’s territory. Over the following decades, both countries sent officials to the island to raise flags and claim the land. Canadians would raise the Canadian flag and leave behind a bottle of whisky for the Danes; they in turn would visit, raise their flag and leave behind a bottle of schnapps (akvavit). This good-natured “whisky war,” as it was often called, lasted for almost 50 years.

In 2018, a joint working group was established by both countries to settle the territorial dispute. In addition to officials from both countries, it also involved Inuit from both Nunavut and Greenland. On 14 June 2022, an agreement was signed in Ottawa by Greenland Prime Minister Múte Bourup Egede and foreign affairs ministers Mélanie Joly (Canada) and Jeppe Kofod (Denmark). The deal was sealed with a final exchange of spirits. The island was divided roughly in half (about 60/40 in favour of Denmark), with the north-south border running along a naturally occurring rift atop the rock. As a result, Canada now shares an official land border with a European country. Following the signing, Nunavut MP Lori Idlout called for the island to be officially renamed Tartupaluk.

See also Northwest Passage; High Arctic Weather Stations; Law of the Sea; Maclean’s Article: Who Own’s the North Pole?.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom