Amphibians are members of a group of tetrapod (four-legged) vertebrate animals derived from fishes and are the common ancestor to mammals and reptiles. Amphibians are characterized by their lack of extraembryonic membranes in their eggs. Amphibians are represented by three living groups: Anura (frogs), Caudata (salamanders) and Gymnophiona (caecilians, tropical, none in Canada).

Description

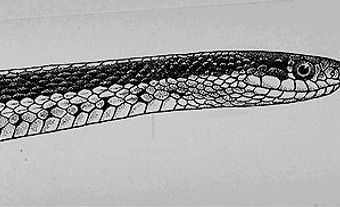

Amphibians are tetrapods or, in the case of some limbless salamanders and caecilians, derived from tetrapod ancestors. They have moist, glandular skin without epidermal scales, feathers or hair. Frogs lack a true tail as adults and have disproportionately long hind legs and exaggerated mouths. Most salamanders have a more typical vertebrate body, with elongated bodies, a tail, and relatively equal-sized front and hind legs. Although easily identified by their lack of scales, salamanders are sometimes mistaken for lizards, which they resemble in body form. All frogs and most salamanders have four toes on the forefeet and five on the hind feet; some salamanders have fewer toes (four on the hind feet in four-toed salamanders and the mudpuppy in Canada) or lack limbs entirely (some species outside of Canada). Caecilians are limbless and have little or no tail. They usually have folds or grooves, which give the body a segmented, wormlike appearance.

Modern amphibians are small. The largest salamanders attain 160 cm; caecilians, 120 cm; and frogs, 30 cm. Typically, living amphibians have two lungs, although the left lung is reduced in caecilians and members of one salamander family (Plethodontidae) are lungless. The heart has two atria and one (sometimes partly divided) ventricle. Poison glands are often abundant in the skin. This poison is distasteful but rarely fatal to predators.

Reproduction and Development

Most species breeding in aquatic situations form large aggregations in spring or after heavy rains. Male frogs typically have distinctive breeding calls. Those defending calling sites may also have territorial calls. In contrast, salamanders make little sound but have evolved elaborate courtship behaviours.

Eggs are fertilized externally in most frogs. Most salamanders deposit small packets of sperm, which are taken up by the female through her vent and held for internal fertilization. Most amphibians deposit eggs in water or moist, terrestrial sites. Eggs are rarely retained in the female until hatching. Most terrestrial eggs hatch only after the larval stage has been passed within them. However, the typical amphibian life history features a gill-breathing, aquatic larva metamorphosing into a lung-breathing adult. Hence, the name of the group (from the Greek “amphi” meaning "both" and “bios” meaning "life").

Striking differences in larval development between groups show their long, divergent evolution. Larval salamanders have forelegs appearing first and hind ones later, and are similar to adults in form and in being carnivorous. Some salamanders remain aquatic, retaining gills throughout their lives.

Frog metamorphosis, from aquatic larvae to terrestrial adults, is more dramatic. Larval frogs hatch with external gills and without legs. The tadpole intestine is long and coiled. The gills soon become internal. Their body becomes globular, with no discernible neck. A small mouth with rasping teeth and beak appears for grazing on vegetation. Later, the hind legs appear as buds and complete their development externally by the time the forelegs develop internally and push through the body wall. Their intestine shortens for a carnivorous diet. The tadpole’s teeth and beak are lost. Their mouth divides. The gills and tail are absorbed. The mouth enlarges to gulp whole animals, and the lungs take over respiration.

Body Temperature

Amphibians are ectothermic (i.e., they have a relatively low metabolic rate that is insufficient to generate enough heat for life processes and thus depend on heat from the environment). Amphibians often function better at lower temperatures than most reptiles but are more vulnerable to desiccation throughout their life cycle. Their eggs lack both protective shells and embryonic membranes, being covered only by a layer of jelly. As larvae and adults, amphibians breathe through their skin and lungs and must keep moist. They are very adaptable, being able to withstand surrounding temperatures several degrees below water freezing by flooding cells with cryoprotectants (e.g., wood frog, spring peeper and chorus frog use glucose; gray treefrog uses glycogen) and to survive losing nearly half their body weight in moisture (e.g., spadefoot toad).

Distribution and Habitat

Amphibians have lost much of their ancestral diversity and size and have survived as small predators, largely in moist or aquatic habitats. Only frog tadpoles are plant eaters, but some may be carnivorous. All salamander larvae and adults in both groups are carnivorous. There are over 8,000 species of amphibians worldwide. Over 7,000 of these species are frogs (including toads), occurring on all major landmasses except Greenland and Antarctica. There are over 800 species of salamanders, restricted mainly to the north temperate zone, and are most diverse in Eurasia and North America. Still, one family (Plethodontidae) successfully thrives in the tropics of Central and South America. Caecilians number a little over 200 species, all entirely tropical. The total of amphibian species is constantly being revised upward, partly because herpetologists now collect more from remote regions and more difficult-to-sample habitats and partly through DNA analysis.

Canada currently has 46 species of native amphibians: 24 frogs and 22 salamanders. None are unique to Canada and most have extensive ranges in the United States as well. None occur in the northern tundra, but several are abundant in the boreal forest. The deciduous forests of southwestern Ontario, the coastal rain forest and interior valley grasslands of British Columbia and the central plains of Saskatchewan and Alberta contain many species that barely range into Canada. No amphibians survived glaciation in Canada; therefore, the ancestors of amphibians now in Canada spread slowly northward following the last glaciation 18,000 years ago.

Biological Importance

Amphibians are a vital part of the ecosystem, forming a significant part of the terrestrial, aquatic and semiaquatic biomass and acting as a biological control on invertebrate members (e.g., mosquitoes). They are widely used to monitor the environment for the effects of acid rain, climate change, ultraviolet light and widespread parasite and fungal infections. Drastic population reductions and some extinctions have been widely studied throughout the world. Many Canadian amphibians are listed as Endangered, Threatened or Special Concern in the Canadian Species at Risk Act.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom